One year after stricter regularization policies were introduced by France's former minister of the interior Bruno Retailleau, undocumented migrants in France are finding it increasingly difficult to obtain legal status. As a result, the number of regularizations fell by 42 percent during the first nine months of 2025.

Bundled in his khaki down jacket, 38-year-old Ladji crosses his fingers. He hopes that this time, his residency permit application, submitted on October 7, will be successful. This Congolese man, who arrived in France in 2016, had previously submitted an unsuccessful application because his file "was lost," he explains bitterly, having spent some 700 euros in legal fees on each application.

Having lived in France for many years, he has a permanent contract as a dishwasher in Paris and speaks impeccable French. He therefore believes he meets all the criteria. "I have meticulously kept all my pay slips, my supporting documents... The administration can reject your application for a single missing document, so I keep absolutely everything," he says. His application has now been submitted. "My lawyer told me it will probably take more than a year, so I'm waiting patiently."

Despite all this carefulness, Ladji puts on a brave face, aware that obtaining a residency permit can be a real challenge, "especially today."

The drop in regularizations, 'a direct consequence of the Retailleau policy'

A year ago, on January 23, 2025, former Interior Minister Bruno Retailleau, through a policy, known as a circulaire in France, bearing his name, tightened the regularization process in France. From then on, to be eligible for exceptional admission to residency (admission exceptionnelle au séjour, AES), a foreigner residing irregularly in France must demonstrate seven years of presence in the country, provide proof of French proficiency, and make sure they have never received an OQTF (obligation to leave French territory). "This new policy reiterates that regularization (…) must remain exceptional," the document stated.

On the other hand, the 2024 immigration law introduced the regularization of workers employed in so-called "in-demand" sectors. The legislation was intended to simplify procedures for employees in approximately 80 sectors experiencing labor shortages and is supposed to allow foreigners to apply for a residency permit if they can provide proof of 12 months of pay slips within the last 24 months of 36 months (3 years) of residency in France.

This is what worries Ladji. "Unfortunately, the job of dishwasher isn't on the list," he points out. His previous experience, a permanent contract with a cleaning company, won't help him either. Only home help is considered to be in high demand in the cleaning sector in the Île-de-France region. "I have months and months of work experience in France and have been present in the country for many years. I think I deserve this residency permit, but you can never be sure," he says.

This doubt is confirmed by the latest official data. According to the Ministry of the Interior, the number of regularizations granted to undocumented immigrants fell by 42 percent during the first nine months of 2025. The decrease reached 54 percent for regularizations based on employment. Only 666 residency permits were granted on the grounds of "in-demand professions" during the first nine months of the year. "What we can say is that Bruno Retailleau's directives to his prefects were, in most cases, met with very attentive ears," Jean-Albert Guidou, a member of the Trade Union CGT's "Migrant Workers" confederation, said. He believes that this decrease "is a direct consequence of the Retailleau policy.”

'Lifelong deportation orders'

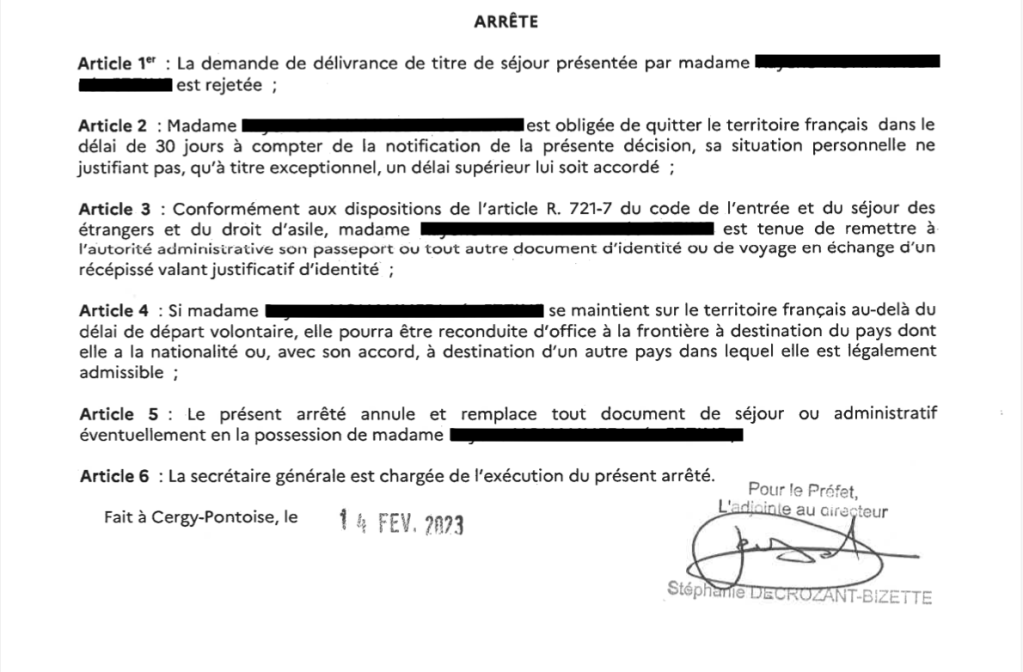

"Lately, we've only seen setbacks," Koundenecoun Diallo, a delegate of the Coordination of Undocumented Migrants of Paris (CSP75), told InfoMigrants. He slammed the policy initiated by Bruno Retailleau as "catastrophic for undocumented migrants." He pointed in particular to the sentence in the January policy that instructs prefects to "systematically" accompany residency permit rejections with a deportation order.

"This is what we call 'lifelong deportation orders,'" Jean-Albert Guidou said. The 2024 immigration law extended the validity period of a deportation order to three years, instead of one year previously. "But in practice, if you received a deportation order 10 years ago, today it can be grounds for rejecting your application if you cannot prove that you complied with it, even if the order has expired," the union representative protested.

This is what frightens Edwige. Since arriving in France four years ago, the Congolese woman has already submitted an application that was rejected and resulted in a deportation order. And now, she fears she will never be able to regularize her situation. Working under a permanent contract at a cleaning company, the 41-year-old woman is waiting until March to submit her application. "By then, I'll have 24 consecutive paychecks," she said, with hope.

But this deportation order hangs like a looming threat. "I'm afraid of remaining undocumented forever," she said. Visibly moved, she lamented being forced into this life of hiding. "I feel humiliated, disregarded. Undocumented people are nobodies. We don't have the right to travel, to have housing, rights… It's as if we don't have a life. It pains me to be in this situation. It makes me unhappy," Edwige said with sadness.

Ladji shares the same frustrations. "I can't take it anymore. Life is hard when you're undocumented," he sighed. "Being undocumented is a weight that always occupies a corner of your mind. It keeps you up at night. It's years of hassle and anxiety."

'Permit renewal is also a real problem'

The tightening of the system is also causing confusion among foreigners who have obtained their residency permits. "Permit renewal is also a real problem," Koundenecoun said. "I've met many people who had been here for 20 years, who were fully integrated and had stable jobs, but who were refused renewal," Jean-Albert Guidou said. "And then it's a complete downward spiral," he added, mentioning a series of setbacks such as the loss of salary, benefits, and even housing.

All of this adds to the problems already inherent in prefectures, namely the lack of resources, the digitization of procedures, and the increasingly long processing times for applications. In January, for example, the CGT union received an appointment at the prefecture for a worker whose application for a residence permit renewal expired in October. "It's in March 2026, even though we submitted the application in August 2025, so this woman will spend months undocumented and risks losing everything," the union representative protested.

Thus, in prefectures, files are piling up. In Seine-Saint-Denis, the French department that hosts the most foreigners, "they are currently finishing processing the applications submitted at the end of 2022," Jean-Albert Guidou concluded.