The social hostel "Dambe So" ("house of dignity") in Bambara, offers a housing solution to migrant agricultural workers in the province of Reggio di Calabria in southern Italy. The initiative intends to fight against the marginalization of migrant farmworkers and promote their integration into society.

Every morning since the beginning of the month of November, the residents of the social hostel "Dambe So" get ready to get on their bikes and cycle to the fields where they will work the entire day. With their hats firmly planted on their heads and their neck warmers pulled up under their noses, the seasonal migrant workers sometimes pedal up to 20 kilometers to pick citrus during high season in the province of Reggio di Calabria in southern Italy.

The luckier ones wait on the sidewalk for a car to pick them up and drive them to the fields. Among them is Sané, a Gambian who has been living in Italy since 2023, and in Calabria for the harvest season. Despite the fatigue that comes with days of intense labor, he was taking Italian classes offered by the social hostel.

Open since the end of 2020, a large beige house accommodates the social hostel “Dambe So”, meaning “house of dignity” in Bambara. The hostel, located north of the San Ferdinando municipality, accommodates up to 72 migrant workers in 15 apartments for a portion of the year.

Poor housing for seasonal workers is a persistent problem in the province. The vast majority of them live in an insalubrious camp on the outskirts of San Ferdinando called the “tendopoli”, literally “the village of tents”.

Racism aggravates the overall situation. Multiple migrants reported the refusals they received when they tried to rent out apartments. “People don’t want to rent to Black people," said Abdoul, a Sudanese who had to fall back on Tendopoli, like many other migrant workers. “This is discrimination,” said Ibrahim Diabaté, a co-founder of Dambe So.

Restoring a sense of dignity

A cultural intermediary, the 56-year-old Ivorian who arrived in Italy in 2008, understands these challenges after having experienced them himself. “After losing my job in the north of the country, I became a farm worker in Calabria for two years. I also lived in the ‘tendopoli’ for six months because I couldn’t find a place to rent,” he said.

His experience became the motor for his engagement to fight against the ghettos built by the public authorities to urgently house migrant workers before later abandoning the places. “We have been throwing money out the windows for 20 years for emergency programs which don’t work,” he said, pointing out the “lack of political will to fix poor housing”.

He and Francesco Piobbichi, the head of Mediterranean Hope, had the idea to create a place offering decent housing to restore dignity to migrants and break the cycle of exclusion in which they found themselves.

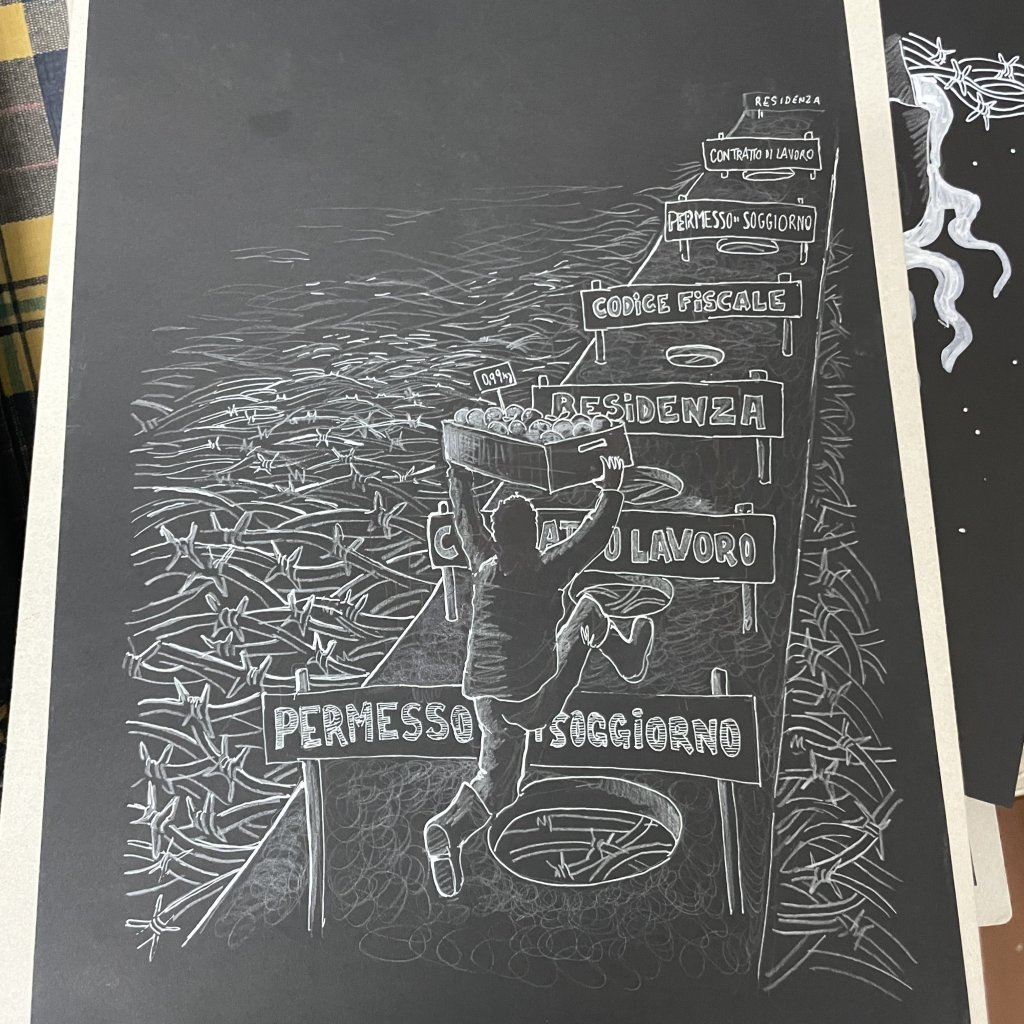

“A house is a very important place; it’s the base. It’s not simply four walls; it’s also the place where the future is built, where one rests. It contributes to giving one the status of a respectable and responsible person,” said Piobbichi. Without a place of residence, it’s impossible to complete certain administrative procedures like family reunification and residence permits. It’s a vicious cycle that aggravates the precarity and marginalization of migrants.

“Dambe So” is based on the empowerment of its residents. “They manage the place and prepare their own meals. We are against assistance; the existing model of dependence needs to be stopped,” said the social worker. The place isn’t a charity either: everyone needs to pay a small rent of 90 euros per month.

The residents can stay in the house for up to six months. A small number of them, like Moussa, live there the entire year. “Everyone buys their food. Sometimes we share and cook together in the evening after work,” said a 32-year-old Gambian who has lived in the home for three years.

“Dambe So” receives up to 200 requests to stay in the house every year. “We only select migrant workers who have documents to avoid problems. This is done mostly by word of mouth. We are also uncompromising on the consumption of drugs and alcohol,” said Diabaté.

Social impact

The project is financed by Mediterranean Hope, which pays the rent and the two social mediators. It also gets support from the SOS Rosarno association, which fights against the exploitation of seasonal migrant workers through small-scale agricultural cooperatives.

Beyond the annual €10,000 grant provided to the shelter, the SOS Rosarno association has been fully involved since the hostel's creation, finding the house and paying the renovation costs. Many of the hostel’s residents also work for Mani e Terra, one of SOS Rosarno’s cooperatives.

The house is converted into a hostel for responsible tourism in the summer, once the harvest season is over. “We receive no state aid,” said Diabate.

Having become a model for dignified housing, the social hostel also helps fight against the prejudices that cling to migrants. The place has a “good reputation among the neighbors” of the peaceful area, said Diabate. Yet acts of racism still persisted. “There are disrespectful attitudes. People throw trash away in front of the hostel. Young people have already targeted workers riding by on their bikes by deliberately opening their car doors and knocking them onto the ground,” said the social mediator.

Read AlsoCalabria, the land across the Mediterranean where migrants are 'treated well'

On the house’s ground floor, a room serves as an office and a meeting place for discussion. There are illustrations on the wall about the exploitation of workers and a portrait of the Pan-African activist Thomas Sankara. This is where various services are offered to residents: legal and union assistance in case of disputes with employers, as well as medical consultations with Doctors Without Borders (MSF), among others. Italian classes are held here twice a week, and a radio program informing workers about their rights is also recorded in the locale.

Piobbichi used to be a social worker for migrants arriving on the island of Lampedusa – a gateway for boats departing from Libya or Tunisia to reach Italy. He highlighted the numerous obstacles that migrant agricultural workers faced in his illustrated book "Fuori dal buio" (Out of the Darkness). "At every stage, they risk having to start over from scratch," he said.