Mixed patrols at the Italo-Slovenian border have been taking place (with some interruptions) since about 2002, but how effective are they at controlling migration at one end of the Balkan route? InfoMigrants joined one patrol to find out and spoke to a legal expert in the capital Ljubljana.

We are at the tiny station of Sezana, just a few minutes' drive from the Italian-Slovenian border. It is early October 2025. The sky is blue and there are very few people waiting at the station. It is here that trains from the Slovenian capital Ljubljana stop. After that, some passengers alighting here may transfer onto a bus to cross into Italy.

This is one of the ends of the Balkan route, where migrants who may have traveled from Asia or the Middle East, through Turkey, Greece and on up through the Balkans, cross Slovenia to enter Italy at the port town of Trieste.

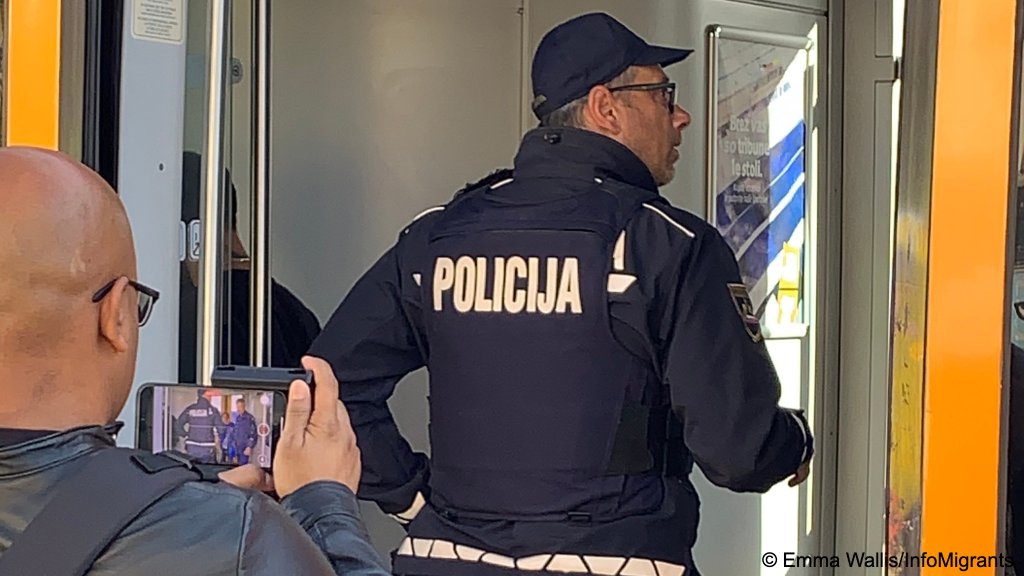

At the appointed time, a couple of police cars roll up, with two Slovenian police officers and one from Italy. Shortly afterwards, Senior Independent Police Inspector Viljem Toskan, head of the State Border and Aliens Department at Koper Police Directorate, arrives.

Read AlsoItaly-Slovenia: Suspension of Schengen pact effective, says Trieste police chief

Joint patrols

The joint patrols, Toskan tells us, began in 2002 with some interruptions along the way. At the moment, there are four mixed patrols per week, three at points in Slovenia and one in Italy.

The times and locations of the patrols change in response to the patterns of migration that the officers observe. Toskan says that recently those trying to enter Italy irregularly have been changing their routes, but one of the ways in is via the train station at Sezana.

The team has arrived about an hour ahead of the train’s arrival, so they can make preparations. Each month, Toskan tells InfoMigrants, he meets with his Italian counterpart Eddy Stolf at Italy's State Police (Polizia di Stato) and his team to discuss their findings and plan out how to respond for the following month.

Toskan says that according to his officers’ data, the number of migrants they have picked up in their patrols before entering Italy irregularly is slightly decreasing, compared to the same period last year. "In the first nine months of last year, over 2,500 foreigners who expressed a renewed intention to apply for international protection were processed. In the same period of this year, there were 1,085 of them, the latter representing a 65 percent drop in the number of foreigners processed."

Read AlsoWestern Balkans: Managing migration and return hubs discussed at London summit

Are the patrols effective?

A decrease could sound like patrols might be helping. And that is indeed what authorities in both Slovenia and Italy believe. Slovenian police data show there has also been quite a significant decrease in the first 11 months of 2025 in the number of migrants entering Slovenia irregularly overall.

In the first 11 months of 2024, Slovenian police recorded 44,000 irregular entries. That figure dropped to 25,000 for the first 11 months of 2025. On December 19, the Slovenian Interior Ministry sent us some more updated data and a statement confirming they think the patrols are very effective.

"The work of Slovenian-Italian mixed patrols is primarily aimed at preventing so-called secondary illegal migration between Italy and Slovenia. In the area of jurisdiction of the Koper Police Department and the Trieste Border Police Sector, a total of 2,809 illegal migrants were dealt with in 2023, of which 2,690 in Slovenia and 119 in Italy. During this period, many migrants walked along the Sežana - Opčine railway line, thereby exposing themselves to the risk of collision with trains running on this route," read the statement.

In 2024, the Slovenian Interior Ministry say: "175 mixed patrols were carried out, with a total of 978 illegal migrants who tried to cross the state border being tracked down. This year, by December 18, 178 mixed patrols were carried out, of which 131 in Slovenia and 47 in Italy, and a total of 480 illegal migrants were detected, of which 444 in Slovenia and 36 in Italy. In addition, the mixed patrols tracked down and arrested a suspect for aiding illegal immigration."

Ursa Regvar, a lawyer and head of asylum and migration at the legal NGO PIC (a legal center for the protection of human rights and the environment), confirms that they believe the Slovenian government data is fairly accurate. But she questions whether the patrols or other policies had any real effect on those numbers.

"Our opinion is that mixed patrols are not really needed, and they don’t really bring anything effective to the table," explains Regvar over the phone to InfoMigrants in December.

Regvar claims her organization PIC has tried multiple times to ask for official information about the patrols and their effectiveness and has been met with silence by the authorities. The government, she says, tells them that the information is covered by secrecy because it is part of a national security issue.

The Slovenian authorities responded saying they work entirely transparently, and they would be happy to share data if organizations apply for it.

Data on border crossings, arrests

At a joint press conference in January this year, the Italian Minister of Interior, Matteo Piantedosi, met with his Slovenian and Croatian counterparts, Boštjan Poklukar and Davor Božinović, during a trilateral meeting in Nova Gorica, Slovenia, on January 20.

At the time, Piantedosi emphasized the significant decrease in irregular migration at Italy’s border with Slovenia.

"The figures show that the temporary reinstatement of our border controls has had a deterrent effect on irregular entries," Piantedosi stated. "From October 21, 2023, to January 15, 2025, approximately 6,200 irregular migrants crossed the Slovenian border into Italy -- a 48 percent decrease compared to the same period from October 21, 2022, to January 14, 2024."

He added: "Since the implementation of this measure, approximately 2,300 individuals have been reported, and 318 were arrested, 160 for aiding and abetting clandestine migration. With specific reference to preventing terrorism, at the same time, we flagged 188 persons to the data bank of the Schengen Police."

Read AlsoGiving migrants a voice via Italian lessons in Trieste

Tricky geography

Back on the ground, the police are waiting on the platform for the train to arrive.

Because of the natural geography around here, the mountains come almost to the sea, it is fairly difficult to choose alternative entry points, thinks Toskan. You have to be a real athlete to climb up into the mountains, and you would also really need to know your way. So, the most likely is that migrants will attempt to follow the road or rail.

When the patrol finds migrants without papers on the train, there are a number of different options available. If the migrants ask for international protection, they are taken to make their application to a center in Ljubljana. Lately, those people applying for protection have been in the majority, explains Toskan.

If they don’t ask for protection, and they find they are registered in another EU country, for instance, they entered Slovenia via Bosnia and Herzegovina and then Croatia, or from the north via Austria, then under the terms of the Dublin regulation, Slovenia can return those migrants to the first EU country they entered. Slovenia also shares a small border with Hungary, but in recent years, since Hungary built a fence across most of its border, it is much more unlikely that migrants cross Hungary before finding themselves in Slovenia and then Italy.

In other cases, says Toskan, depending on the case, the Slovenian authorities are able to return migrants to their countries of origin.

Read AlsoForeign minors an 'unsustainable emergency,' say mayors of northeastern Italy

Asylum in Slovenia

Slovenia, says Regvar, is a country that is not very "asylum friendly." In fact, from those 25,000 irregular entries, only 3,800 actually lodged an asylum application in Slovenia this year.

Slovenia is mostly a transit country, concedes Regvar, but the asylum system is also relatively forbidding. In order to lodge an application, a migrant needs to wait between three and 20 days in a shipping container in "terrible conditions," says Regvar.

"The Ombudsman stated two years ago that the conditions in these containers are so bad, they hinder the right to asylum," states Regvar.

These conditions, she thinks, "basically push people to leave before lodging their asylum claims." Even if you do lodge a claim, there is a waiting time of up to three years for the government to make a first instance decision. "We have a situation now, where people are waiting for up to two years for a personal interview," says Regvar, "so the decision process is extremely long here."

The grant rate is also low. Since 1995, says Regvar, just 1,600 people have been granted asylum. Since the new regime took power in Syria last December, the Slovenian government has also suspended all decisions on Syrians. They were among the few nationalities who had previously been granted asylum on application.

In 2024, around 180 people were granted asylum. This figure included Ukrainians, and were not all about first decisions, but also included prolongation of status, explains Regvar.

Slovenia "doesn't really have diasporas, or other communities, so people can really feel alone and isolated here. They don't have family members here or other members of their communities. So, really the only people who might attempt to apply for asylum are people who don't have anyone else anywhere in Europe."

Read AlsoNortheastern Italy – number of 'invisible' migrants up in Trieste

Provision

During the asylum process, the Slovenian government doesn't provide free legal aid either. PIC does offer it, but most potential asylum seekers are not provided with the information about their rights that they should have access to, thinks Regvar. This hinders the whole process for them, she adds.

Anyone who does apply for asylum is given lodging and food, and they are provided with 18 euros a month as subsistence. "This doesn't even cover the monthly bus fare," says Regvar, underlining that things in Slovenia are "extremely expensive."

Asylum seekers are however allowed to work after three months, and they have free movement from the asylum center, but they are meant to stay within the municipal authority where they are lodged. So, most of them are accommodated in Ljubljana, which means they can't officially leave the capital area. If they are found, say in Sezana, the police are expected to escort them back to their accommodation.

But this puts a strain on the police, it is a lot of effort for them, thinks Regvar. "And is it really helpful?" she asks.

Read AlsoItaly: Five arrests at border near Trieste

Relatively young and mostly male

The majority of migrants that the patrols come across are men, between about 18 and 33, explains Toskan, but there are some women and children among them too, and occasionally men over 50, but that is much rarer.

Mostly, those trying their luck on the train are the ones who are relying less on help from smugglers. The smuggling gangs tend to transport people by car and are picked up by our road checks, explains Toskan in Slovenian.

Sometimes they are able to arrest the smugglers themselves, but often the gangs are operating out of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia, explains Toskan. "We might pick up someone who is transporting foreigners in their car, but these drivers are just small fry in the bigger organizations."

Quite often, the police find that the drivers are citizens from Ukraine, says Toskan. Alternatively, they can be citizens of other Balkan countries, like Serbia, Croatia, or occasionally also Slovenians. Occasionally, the drivers might already have an EU passport, but have their origins in the country of the migrants they are transporting. For instance, Toskan says they have found some cases of Chinese origin people who have been living in the EU for a long time and were trying to transport Chinese migrants through Austria and Italy.

Read AlsoItalian minister highlights decline in irregular migration at Slovenia border

Cooperation and European data

The Slovenian police cooperate with patrols in Italy and Croatia, as well as working alongside Frontex, Europol and Interpol on these investigations.

The patrol sets up a computer in the station waiting room, so they can check the documents and fingerprints of anyone they find on the train, and that way, they can know if they are in Slovenia legally or illegally and whether or not they are registered in another European country too.

As Toskan finishes talking, a red train pulls in at the long, low platform. His mixed patrol officers stand to attention and as the train slows to a stop, they enter the train to check passports and documents.

Read AlsoPassing through: Croatia's 'invisible migrants'

One lone unaccompanied minor

On the first train, they find one lone unaccompanied minor. According to the police, he is just 15 years old and after questioning him, they transport him back to the center for unaccompanied minors in Postojna.

His presence on the train doesn't surprise Regvar. Unaccompanied minors have the highest absconding rate in Slovenia, she explains.

Most asylum seekers abscond after an initial registration anyway, but that is particularly the case for unaccompanied minors. Like in neighboring Italy, Regvar also notes the presence of lots of young people from Egypt, as well as Afghanistan, Syria and Bangladesh.

Another problem with the system in Slovenia, thinks Regvar, is that there is "no real screening done or identification of people's vulnerabilities. No one really checks if someone is a potential victim of trafficking, so people are able to transit unnoticed and unregistered, which makes them vulnerable to future exploitation, as there is no one to flag who might be vulnerable to future dangers."

The team informs us that another of the patrols on a road has also stopped four or five migrants not far from the Italian border in a car. In the group are three adults from Turkey, they say. They have asked to apply for asylum in Slovenia. They normally travel by car, a police officer tells InfoMigrants.

Read AlsoItaly re-enacts controls along Slovenia border

Tension

The train pulls out, and the few passengers disperse. About an hour later, another train pulls in. This one has around 13 migrants on board, who are all subject to the police controls. The train conductor follows them off the train and is clearly displeased.

He says that he doesn’t want to be filmed, because migrants believe that it is the staff of Slovenian railways who called the police, and that is not true, he insists. "My job is to just check who has a ticket," the train conductor says. "We don’t look at the color of someone’s skin or nationality. We are just running a commercial business."

The 13 migrants picked up by the police file off the train in a line, accompanied by the police and are ushered to the waiting room, where the police check their documents and identity and then wait with them for a minibus to transport them back to Ljubljana.

There are no more trains expected, so we too pack up to catch the last bus back to Trieste. At the border, the Italian police enter the bus and check everyone’s documents on that bus too. We wait a while for the procedure to finish, and then the bus trundles on down the mountainside towards the sea.

Read AlsoAre efforts to stamp out migrant smuggling on track?

A 'crisis' useful for politicians?

The relatively few people picked up by that day's patrols are somehow more indicative of the wider situation in Slovenia, thinks Regvar. In her view, the so-called "migration crisis" isn't a crisis at all, and the word has been created for political ends.

"We feel that this is something that the politicians have brought up in order to make it appear to the public as though there is still a crisis when it comes to mass migration," thinks Regvar. This, she believes, is "because public policy needs to constantly create a bit of panic in order to justify their [the politicians] own policies when it comes to migration. Whether that be additional police or money for control technologies, but this doesn’t mean that the policies they are taking are even needed or effective. That is why I ask, what is the effectiveness of the mixed patrols?"

Regvar adds that since 2016, irrespective of the government in power, and whether their politics have been to the left, right or center of the political spectrum, the migration policies in Slovenia have been fairly strict.

"Migration is always a big topic when it comes to elections. Migration, unfortunately, is a way to gain political points."

Read AlsoNumber of irregular migrants decreases in Slovenia

Statistical disparities

Regvar admits that it is hard to speculate about why arrival numbers appear to be on a declining trend. "The modus operandi of the smugglers changes all the time, so it is hard to provide accurate information about that."

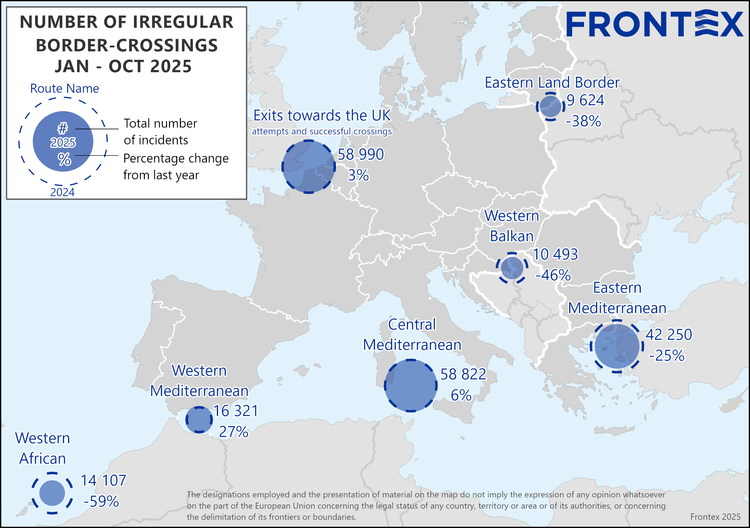

But, based on what some individuals have told the organization she works for, Regvar thinks that two things might be happening. Some migrants are probably going from A to B with smugglers and just not getting detected. This could also explain why Frontex' data for the first 10 months of 2025 shows fewer than half the number of irregular crossings detected across the whole of the Western Balkan route, compared to the actual number of irregular entries (25,000) in Slovenia (for the first 11 months) during roughly the same period.

Frontex data records irregular entry attempts, not the number of people, so some people might be recorded multiple times at the same or different borders along the route. So, you might expect their data to be higher than the actual number of people who entered a country at the end of the same route.

A lot of people might have information from the smugglers, thinks Regvar. Some know that in Slovenia, although their entry is registered, they do not then face many controls while crossing the country, despite the presence of the mixed patrols.

Regvar thinks this knowledge might mean that some are traveling in a different way across Slovenia. Perhaps 'allowing' themselves to be registered, because under the Dublin regulation, they would prefer to be returned to Slovenia, with relatively lax controls than neighboring Croatia, for instance.

Or, they allow themselves to be registered in Slovenia because once they have left the country, which most do, they rarely come back, confirms Regvar.

For its part, the Slovenian Interior Ministry said they intend to continue the patrols in 2026: In an email statement sent in December, they confirmed that "the significant reduction in the number of illegal migration [attempts] is partly also a result of the successful work of mixed patrols on the Slovenian-Italian border. Based on the data, we assess the work of mixed patrols as successful and we will continue this method of work in the coming year."

InfoMigrants was also in touch with Chief Inspector Toskan's Italian counterpart, but unfortunately, despite several messages and phone calls, he was unable to obtain permission from the Italian Interior Ministry in Rome to be able to talk to us.

InfoMigrants also approached the Italian Interior Ministry directly to ask for comment on the joint patrols, but did not receive a response.