Hungary has reiterated its position on migration, saying that it will not "accept a single migrant" and will not participate in the European Union’s new migration solidarity mechanism. A new pact on migration and asylum across the EU is set to take effect in June 2026.

Hungary has reiterated its position that it will not "accept a single migrant" and participate in the European Union’s new migration solidarity mechanism, German news agency dpa reported yesterday (December 10).

The announcement on Wednesday at a press briefing by Gergely Gulyás, chief of staff to Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, reaffirmed the country’s longstanding opposition to compulsory or voluntary redistribution of asylum seekers and its rejection of the European Union's plans to implement a bloc-wide migration policy. The announcement is poised to set the stage for renewed tensions between Budapest and Brussels ahead of planned changes to the EU’s asylum system which sets a mandatory migrant quota for every EU member, including Hungary.

Days earlier the European Union interior ministers approved the solidarity mechanism, under the upcoming Migration and Asylum Pact, which is due to take effect in June 2026. After years of political gridlock, EU interior and justice ministers agreed on a system designed to ease pressure on frontline states by creating a new form of burden-sharing.

Read AlsoEU ministers agree on new migration reform plan for 2026

A solidarity system

Hungary’s refusal to participate is not unexpected. Since the 2015 migration crisis, Budapest has maintained some of the harshest policies in the EU, erecting border fences, limiting access to asylum procedures, and insisting that the country will not accept mandatory quotas of people seeking protection.

However, the EU's migration policy overhaul introduces faster deportations, safe-country designations, and the idea of return hubs, while a 430 million euros solidarity pool aims to help states, even while some governments refuse relocations or funding.

Under the new rules, member states will be required to contribute to asylum management in one of two ways: either by taking in relocated asylum seekers or by providing financial or material support to countries receiving high numbers of arrivals. Governments will be expected to make annual contributions based on agreed targets, although the system allows for some flexibility on how solidarity is provided.

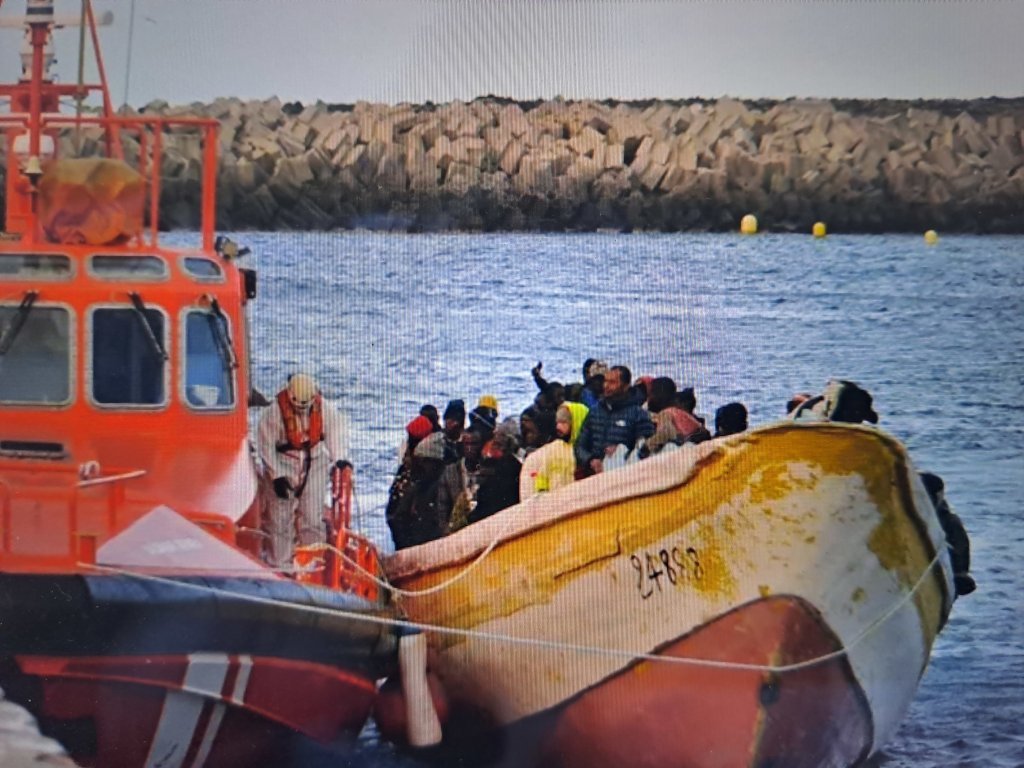

The reform aims to prevent the bitter political standoffs seen in 2015 and 2016, when migrants and asylum seekers arrived in Europe in large numbers and member states struggled to coordinate responses.

Frontline countries like Italy, Greece, and Malta, which serve as the gateway countries to the rest of the EU, have long argued that the EU’s asylum pressures have been unevenly distributed, leaving frontline states responsible for the majority of arrivals.

Read AlsoHungary repeats calls for EU asylum rule exemption

Long-running tensions with Brussels

Hungary’s position has put it in repeated conflict with EU institutions. In June 2024, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) imposed a one-off fine of 200 million euros on the country for failing to comply with prior asylum-related rulings, along with a daily penalty of 1 million euros until the government begins processing asylum applications in line with EU law. The court cited Hungary’s "de facto halt" of asylum procedures and the unlawful detention of asylum seekers in transit zones.

This week’s announcement appears to signal that Budapest has no intention of adjusting its approach. "The EU has no authority to decide with whom Hungarians should live," Gulyás said, pointing to a 2016 referendum in which voters rejected what the government described as the EU’s proposed "forced resettlement" plan.

EU Migration Commissioner Magnus Brunner expressed disappointment at Hungary’s decision, saying on German public broadcaster ZDF that the pact would "bring advantages for everyone." He reminded member states that commitments made at EU level must be respected, and that solidarity under the new pact is "flexible on the one hand, but mandatory on the other."

Read AlsoHow Hungary is violating EU law on refugees

Not eligible for solidarity funds

Budapest has also argued that the new system disadvantages countries that are transit points rather than the first points of arrival. The EU’s solidarity mechanism is tailored specifically to assist countries processing initial asylum claims or receiving high numbers of sea or land arrivals.

According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the EU member states receiving the largest number of first arrivals in 2025 so far are Italy, Greece, Spain, Cyprus, Bulgaria, and Malta. Together, they have recorded 145,592 arrivals this year. Hungary, by contrast, is not a frontline arrival country under EU definitions.

Budapest has accused the European Commission of "underestimating migration pressure" on Hungary and claimed that only countries aligning with Brussels' political agenda receive support. The Commission rejects this, saying the solidarity system is based on objective criteria.

The dispute over migration comes at a politically sensitive time. Hungary is heading towards national elections in April 2026, and for the first time in over a decade, Prime Minister Orbán faces a serious electoral threat. Polls in the autumn showed the newly formed Tisza Party, led by former insider Péter Magyar, outpacing Orbán’s ruling Fidesz party by double digits.

Political analysts say migration remains a central pillar of Orbán’s political messaging — one that reliably mobilizes supporters and positions him as a defender of national sovereignty against the EU. By taking a hard line on the Migration Pact, Orbán is doubling down on this narrative, perhaps in the hope that this will help him strengthen his popularity with the electorate at home.