Numerous Ethiopians have been taking the northern route every year toward Europe via Sudan and Libya. Growing poverty and regional conflicts have been sapping the country for years, driving many young people to leave in search of safety and opportunity.

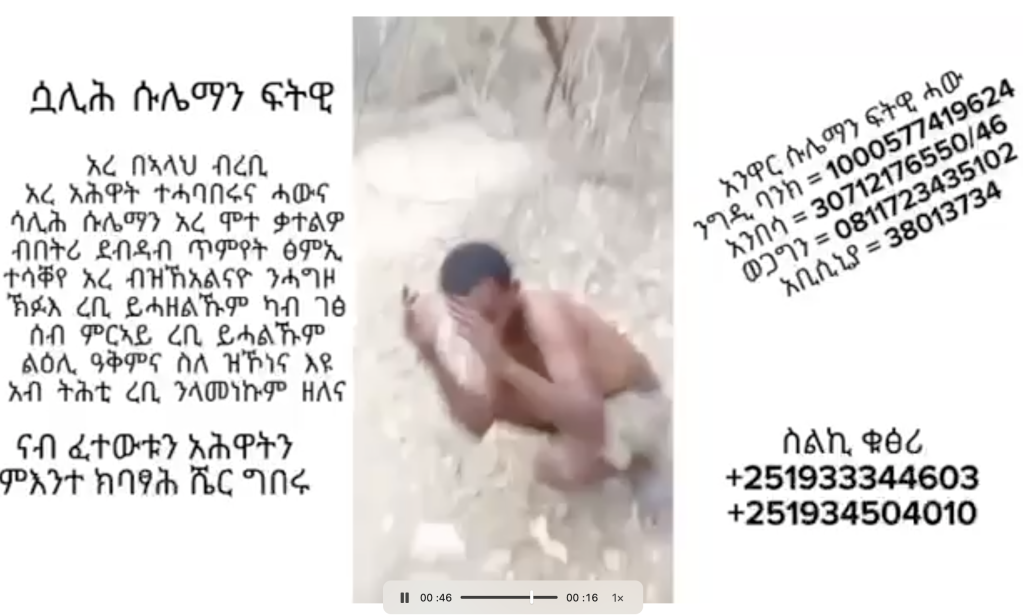

It’s a violent image that has become all too common. Salih Suleiman, excruciatingly thin and crouching, begs throughout the video: "Save me", "I’m dying of hunger, please", "send money". The 27-year-old, detained in Libya along the migratory route that leads to Europe, gets beaten with a stick after each of his pleas. His persecutors are demanding a payment of 1.4 million birrs [the Ethiopian currency, equal to 7,900 euros] in exchange for his freedom.

The video of the former teacher from the University of Raya in the Tigray region has become viral. Yet it is not rare: similar images of migrants being tortured and threatened are flooding social media in Ethiopia.

Tens of thousands of people like Salih Suleiman leave Ethiopia every year through informal migratory routes. About 250,000 migrants opt for routes leading to the Gulf countries, South Africa and Europe, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM). While the eastern path via Yemen is the most common, the route leading to the European Union (EU) and United Kingdom remains an alternative for many individuals. In its latest report on the northern route published in 2024, the IOM noted that "movements tracked along this route almost tripled", going from 6,200 in 2021 to 17,700 in 2022. These trends are "likely underestimated" because of difficulties in collecting data, added the IOM.

The onset of the Sudan conflict in April 2023 has logically discouraged crossings along the northern route. "The IOM’s flow monitoring points at Metema and Kurmuk [Ethiopian localities on the border with Sudan, editor’s note] have seen a significant increase of people returning to Ethiopia through this region since the beginning of the war," the IOM’s office in Addis Ababa told InfoMigrants. Some 30,000 people were detected by IOM staff between April 2023 and September 2025 at this border -- this figure represents movements and therefore includes people going to or returning from Sudan.

Read AlsoWar in Sudan: 'In Darfur, some people have been displaced for the third or fourth time'

New routes have emerged since the war in Sudan broke out. Some migrants choose to apply for a student visa issued by Russia, and then try to reach Poland by crossing the Belarusian border. Another more recent solution is a "package" including a Schengen visa and an airplane ticket for Greece or Romania, offered by smugglers for two million birrs, or about 11,300 euros. The migrants later take a bus to France, before attempting to cross the Channel to reach the United Kingdom, the primary destination country for Ethiopians, according to the IOM.

'We pay our rent and eat, that’s all'

Many Ethiopians are leaving their country because of a bleak economic outlook. Inflation, at 13.5 percent in 2025 according to the Ethiopian Statistical Service, hit the population hard and plunged many into precarity. The poverty rate in Ethiopia rose to 43 percent this year, according to the World Bank, putting an end to decades of progress. Numerous young graduates struggle to find a job that would allow them to cover their daily expenses.

"As soon as they finish their studies here, young people want to leave. It’s normal, it’s easier in Europe. In Ethiopia, life has become so expensive," sighed Birhan*, a taxi driver in Addis Ababa, whose sister lives in Liverpool, England.

Mikael, for his part, has a friend who left for Greece, and another to the United Kingdom. "I understand them,” he said. “It was already difficult with the previous government. Yet with this one, we are suffering [the current prime minister Abiy Ahmed has been in power since 2018, after the fall of his predecessor Hailemariam Desalegn, editor’s note]. We pay our rent and eat with what we earn, that’s all. We survive." Mikael juggles two jobs so he can pay for his four-year-old daughter’s private school. "I want to give her the best. A comfortable future."

A country sapped by conflicts

The economic hardship is compounded by insecurity in several regions of Ethiopia. A bloody conflict between federal forces and a nationalist militia known as Fano has been raging since April 2023. The consequences for the population have been dramatic. At least 7,700 people in the Amhara region have died in the conflict between April 2023 and April 2025, according to an assessment published by the British government.

Only a few years ago, Abraham lived from tourism and small jobs as a carpenter. The conflict upended his daily life. “Insecurity along the roads stopped us from moving, and made the tourists flee,” he said from the housing for asylum seekers in England, where he was living. “The government repression toward anyone suspected of being part of Fano has also become stronger. I couldn’t make a living, and I was scared: I was facing a dead end. I left my region for good in the summer of 2024.”

Abraham transited through Sudan, Libya, Italy, France and survived for two months at a migrant camp near Dunkirk. After a "traumatic" Channel crossing, he reached the United Kingdom in the beginning of November 2025.

Farther north in Ethiopia, the Tigray region is struggling to recover from the war that pitted the federal government against the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF) from November 2020 to November 2022. Aferom, from western Tigray, decided to leave for Europe just after the war ended in December 2022. "I'm an orphan and I had no one left there. I owned a small barbershop, but everything collapsed with the war," he said over a steaming cup of coffee in Addis Ababa. "My only option was to leave. I wasn't the only one; everyone wanted to escape."

The young man contacted a smuggler near his home before traveling through Sudan to reach Kufra, in southeastern Libya. Aferom tried to board a boat bound for Italy four times. The police or a Libyan militia prevented him from leaving every time. "I lost friends; one of them was beaten to death. I also spent a lot of money, because the crossing costs between 1,000 and 1,300 US dollars [between 850 and 1,100 euros], and the militias extort money from Ethiopians. Then I met people who had been there for four or five years. All of this made me lose hope." Exhausted and discouraged, Aferom decided to return to Ethiopia through the IOM's "voluntary return" program.

The dangers that exist along migratory routes has not stopped people from leaving the country, said Yirga Alemu, an independent researcher in sociology. "The war is finished but the political and economic situation is so tense that families are pushing their children to leave out of fear that a new war will break out," he said. “It’s true that the arms have been silenced, but living here is impossible.”

‘I wouldn’t even try the legal route’

Yet it’s difficult for young Ethiopians to leave once their decision is made because of the complexity of the Ethiopian bureaucracy. "A passport costs 5,000 birrs [28 euros, editor’s note] – an exorbitant price for many families, said a researcher specialized in migration based in Ethiopia who asked to remain anonymous. "Even if you can buy one, it takes between six months to a year to obtain it. For people in danger, who are fleeing conflicts, it’s simply impossible."

The European Union has also tightened visa conditions for Ethiopians. Since April 29, 2025, Ethiopians cannot benefit from a multiple-entry visa. The delay for treatment of visa requests has gone from 15 to 45 days. These measures discourage potential migrants from even filling out a request form. "If one day I decide to leave, which is possible, I wouldn't even attempt the legal route," said Mikael. "Everyone here knows it's impossible."

Read AlsoIrregular EU entries down as new routes emerge

Aferom can’t even fathom leaving again six months after coming back. He lives in a small studio in eastern Addis Ababa, with his "five-year-old girl and three-year-old boy", who he is raising alone. On his way back to Ethiopia six months ago, Aferom learned that the mother of his children had been killed during a battle in Khartoum. "My children are my responsibility, so I'm doing everything I can to make sure we all live well. They're counting on me."

*The first name was changed