In the north-eastern Italian city of Trieste, a network of organizations have joined together to create a day center for migrants arriving along the Balkan route. But their center does much more than that, explains the director of one of the charities responsible for running the center, Gianfranco Schiavone.

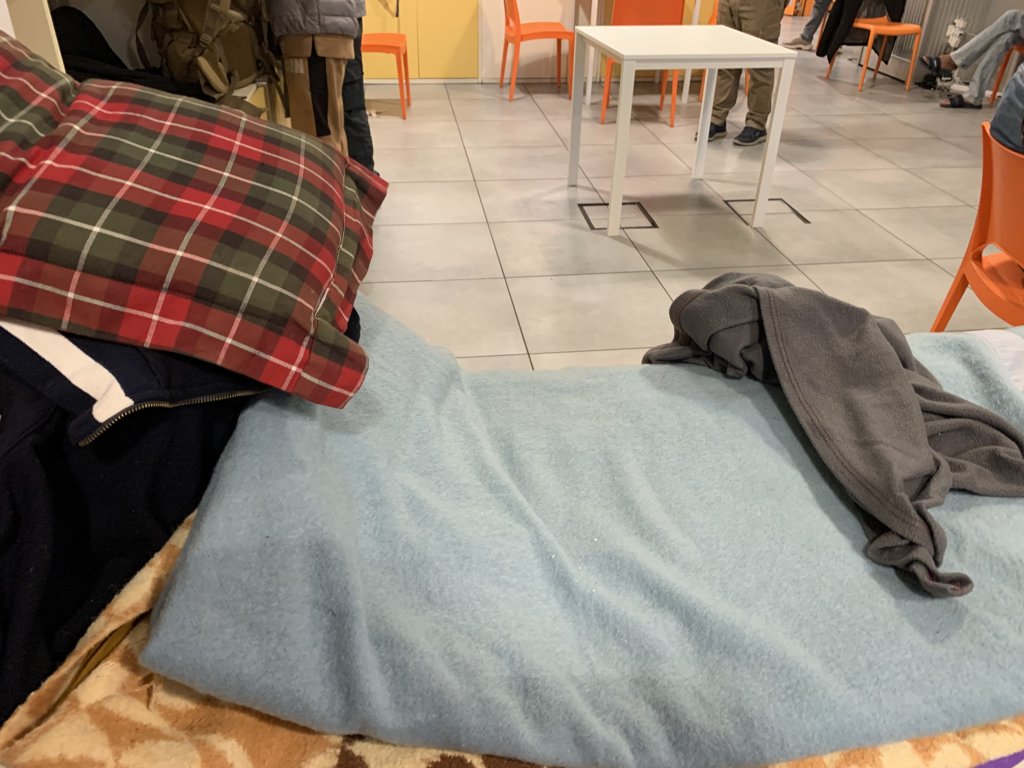

We are sitting in a corner office of a busy day center in Trieste towards the beginning of October. Dozens of migrants are using the facilities, even though the skies are darkening outside and the center is about to close. Chatter in a variety of languages fills the rooms, a group plays table football, others gather around their phones while they charge them using banks of plugs provided for the purpose.

There are toilets and bathroom facilities here and a medical check-up center for anyone needing to see a doctor. Cultural mediators are on hand to help answer questions and provide information, and there is access to legal help for anyone wanting to know their rights or seek asylum.

"This center wasn’t set up for migrants initially [in 2009], but for homeless people," explains Gianfranco Schiavone, director of ICS (Italian Consortium of Solidarity) that helps support migrants, refugees and asylum seekers in Trieste. Schiavone is also a jurist, or legal expert, and works with ASGI, the Italian Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration.

'Anyone who doesn't have a place to go can come here'

Schiavone explains that over the years, the majority of those who were homeless in Trieste turned out to be migrants, and so, the center evolved into helping them. Volunteers from various different associations work at the center and help run it. The center was initially set up by the volunteer charity San Martino al Camp founded by a young priest in the seventies, to help those who are most fragile in society. Today, volunteers from San Martino have been joined by people from Schiavone’s non-profit ICS, and people from the International Rescue Committee (IRC) as well as the Italian sea rescue organization Resq. The association DONK provides medical help and the Valdesian Diakonie is also present as well as the ASCS - Agenzia Scalabriniana per la Cooperazione allo Sviluppo).

"Anyone who doesn’t have a place to go can come here," says Schiavone. "It can be chaotic, sometimes there are 100 people here, but for those who are in transit, or those who want to ask for asylum, this place offers them support.”

Schiavone is very clear about the purpose of the center and the organization's role here: "Just offering help doesn’t really change the situation, but our aim is to change things. […] our project is not just about providing humanitarian aid, we have a political project, which is to stand up to the institutional illegality we see going on."

Read AlsoAssociations: Over 100 migrants living on streets of Trieste

'Institutional illegality'

The 'institutional illegality' Schiavone is referring to is, in his opinion, a willful determination on the part of the authorities in the region to ignore the law, which provides that anyone asking for asylum should be offered a place in the state reception system.

The lawyer says that the humanitarian aid and information that he and the other volunteers provide is in direct contrast to what he says is a "breach of contract" on the part of the Italian authorities, most of which are right-wing in this region which has long been mainly governed by politicians from parties coming from the center to the right-wing, like the League (La Lega), Meloni's Brothers of Italy party and Forza Italia with the exceptions of one or two big cities, like Venice and Udine, which tend towards candidates from the Democratic party (PD). The region currently is run by a right-wing alliance, led by the League.

"The law says that anyone who says they want to ask for asylum, even before they have started the formal process, they should be offered state help. But in reality, it doesn’t always work like that. There are not enough places for everyone, so that means that many people wanting to claim asylum remain on the streets, sometimes for several weeks."

Schiavone says that the authorities doing this are hoping their approach will act as a kind of "deterrent." He estimates that on average there might be around 30 people a day asking for asylum in Trieste, as around 70-80 percent of those transiting the city are hoping to go on elsewhere, to northern Europe and so don’t want to stay and register anyway.”

"I think they just want to push people away by saying there are no places available. They don’t want to find them a place, because that will force them to continue their journey."

In a way, admits Schiavone, the authorities' approach is working, since many of those who might have stayed, end up moving on too, as they think there is no help for them here, but, perhaps because of his legal training, he feels that if the law sets down a principle, then it should be followed and help to those who seek it should be available.

Read AlsoNortheastern Italy – number of 'invisible' migrants up in Trieste

'For me, it is about the legal principle'

"For me, it is about the legal principle. We receive attacks from the local politicians, who often don’t like what we are doing. But we are attacked in my view, because we insist that the rules and the law should be respected."

Schiavone says he is "proud" that over the years, he and the other organizations working out of the center have helped thousands of people seek and gain access to the reception system in Italy. Some may have had to wait longer than others, but all those who have sought help have received it.

ICS also works hard to try and document, with meticulous research and data recording, the number of people who come through Trieste, in order to provide as accurate a picture as possible of arrivals along the Balkan route.

Read AlsoSmuggling ring dismantled in cross-border op with Italy

Contrasting data?

Interestingly, the data that ICS has been gathering is in stark contrast to the data provided by Frontex for 2024, says Schiavone. The lawyer said that their data is based on direct meetings in person with all the people who come through the center or seek help via their organization. They also operate in the town square with volunteers who give out food every evening to those migrants who are sleeping rough in the town or are not yet in the reception system.

"We gather data meticulously to try and make sure that the politicians and the public opinion are confronted with the reality and the fact. We document everything very carefully. So that no one can deny the actual figures and the quantity of people coming through here. We are trying to make sure that everything is very transparent. And that is what makes Trieste quite different. The same approach might be going on in other cities, but it is not being monitored in the same way as we try to do here. So, in other places, often no one knows exactly how many people might be falling through the system and being abandoned."

According to data from ICS, 2024 saw about a ten percent reduction in the number of people arriving along the Balkan route. But that was in stark contrast to data from Frontex, which Schiavone says registered around a 70 percent reduction in the numbers traveling the Balkan route in 2024. In fact, Frontex said in January 2025, they had registered a 78 percent reduction in the number of those traveling the Western Balkan route. They said they had detected just 21,520 irregular border crossings on that route in the whole of the year.

Schiavone says he has asked Frontex for clarification on this issue, but so far received none. His conclusion is that Frontex data is not so reliable because they work of those who are intercepted along the route, and not really on the overall people traveling it.

Read AlsoItalian region sets new criteria for hosting migrant minors

'Invisible' journeys

"We are convinced that now people are still traveling the route, but in a much more ‘invisible’ manner. Because the mechanism of human trafficking has refined itself. The traffickers are more organized now," says Schiavone.

He admits that there are far fewer people using the reception centers along the way in Serbia or Bosnia Herzegovina for instance. He thinks that is because "the people who are working as traffickers are also now running their own centers and accommodation places along the way. And the transit times are much, much faster than they used to be. So, Frontex might think that there are fewer people than there had been, but just because you can’t see them, it doesn’t mean they are not there."

By way of additional evidence, Schiavone says that in 2024, the Slovenian authorities registered more than 40,000 immigrants. "How did they get there?" he asks rhetorically, "They weren't all just parachuted in, were they?" Schiavone explains that their figures come from PIC, a legal association in Slovenia with whom they work. This organization counted 46,192 new arrivals in Slovenia in 2024, the majority from Syria, Afghanistan and Turkey.

Schiavone says that roughly half of those transiting Slovenia will make their way on through Austria, and around half through Italy, although these are very rough estimates, he admits. However, continuing with his logic, Schiavone thinks that if they saw around 13,000 to 15,000 people in 2024 come through Trieste, there were probably at least 5,000 who continued at night and just didn’t stop at all in the town, or others who came through nearby Gorizia or Udine.

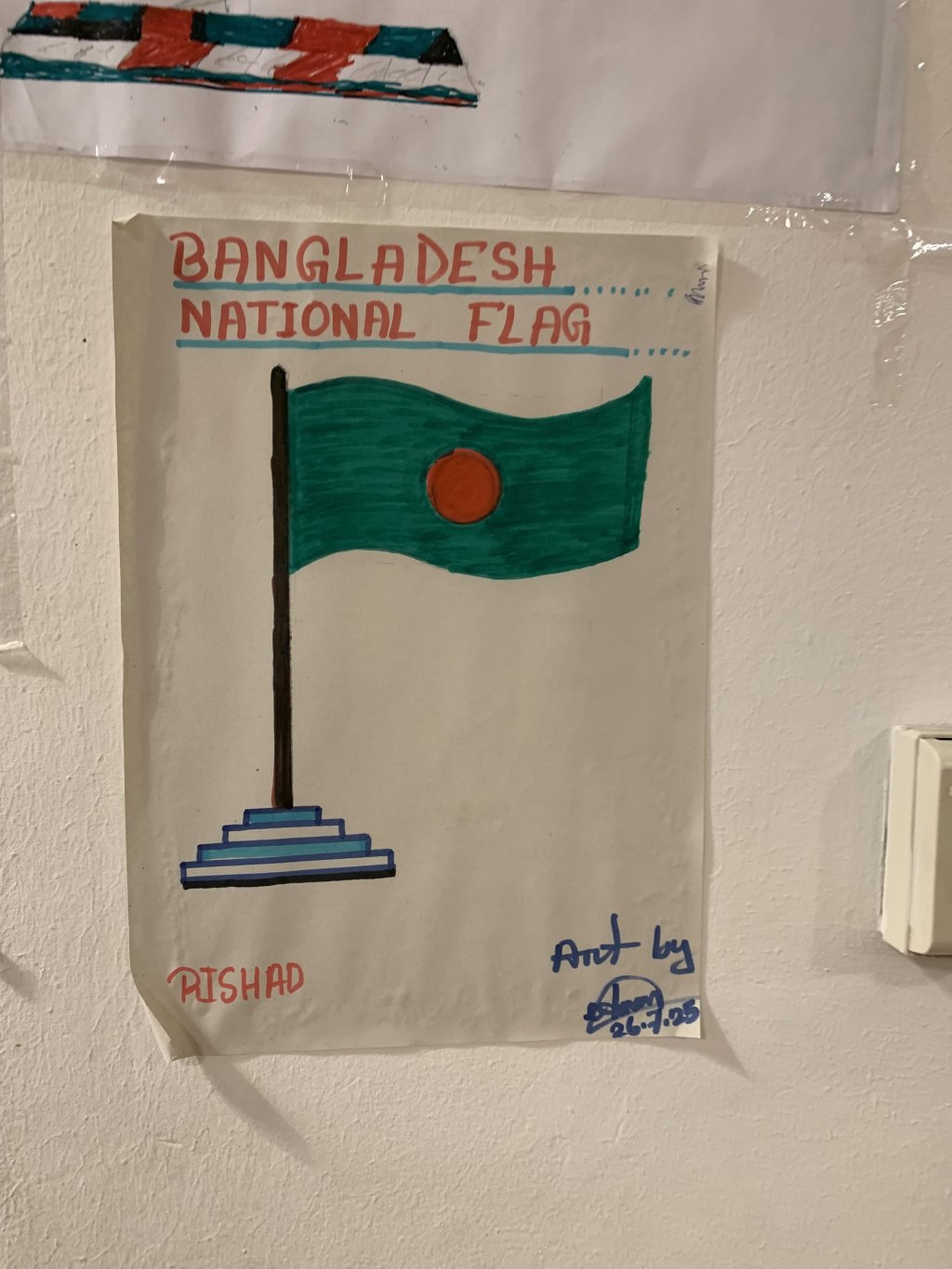

Schiavone says that the nationalities of those traveling the Balkan route and arriving in Italy change over time, but the majority tend to come from Afghanistan, Pakistan, and then some from Bangladesh, Nepal and Iran. A few years ago, more Syrians came this way, says Schiavone but that has changed in recent years.

Italy = 'Plan B'

He says that their data hasn’t yet marked a change following Germany and Austria’s reintroduction of stricter border controls, but what they have noticed are what he calls the 'Plan Bs'. These are often migrants who have already spent some time in Germany or Austria and either been sent back to Italy, or decided to make their way back to Italy to apply for asylum there, sometimes after having been refused asylum in Germany or Austria.

"These people are arriving in much better condition than those who used to arrive from the Balkan route, after sleeping for weeks or months in forests etc. Some of them will arrive very well dressed, even with a suitcase," observes Schiavone.

Sherkhan from Afghanistan was in a way one of those people. He now works with IRC as a cultural mediator and speaks perfect unaccented Italian. Sherkhan explains that he arrived along the Balkan route in 2016, traveling it when he was just 19, nearly 20.

In Italian, he explains that his mother tongue is Pashto, he also speaks Dari, Farsi, English, Urdu, Hindi and of course Italian. "When I traveled the route, if things went well, you could get from Afghanistan to Europe in about two or three months," recalls Sherkhan. "Now it can take five or six months, even if things are going relatively well."

He says some of those arriving in Trieste say they left Afghanistan in 2021 or 2022. "It is really difficult to cross some countries now," admits Sherkhan. His intention was to reach northern Europe too, he says when he set off from Afghanistan. In fact, he did arrive in Germany and spent a few months there, but then they were due to send him back to Hungary via the Dublin process, which is where his fingerprints were first registered, and so Sherkhan decided to leave for Italy.

There, after spending a few weeks on the streets, he met up with ICS volunteers who helped him apply for asylum. And once established, he decided to go to work for IRC, to help people like himself and provide them with the information they might need, should they decide they want to stay in Italy.

Read AlsoItaly: Controversy in Trieste over Caritas migrant center opening

A collection of volunteers provide as many services as they can

Sherkhan hasn't yet received Italian citizenship. "You really have to sweat for that," he laughs, but it is clear that he is well integrated into the team at the day center and in his life in Trieste. He and Schiavone joke and laugh as they are talking and exchanging information about how the day unfolded in the center.

Living proof of Schiavone's principles, that for those who seek help, there is help on offer in Trieste too. As the day center closes, Schiavone, many of the volunteers and cultural mediators, as well as most of the migrants head outside, towards the next stage of this joined up 'political project'. Everything is coordinated and linked, explains Schiavone, from the services provided by the day center, to the food distribution in the evening provided by the organization Linea d'Ombra.

Outside, as the night sky darkens and the lanterns twinkle, a long queue of migrants snakes around the town square, not far from the central station. The migrants are waiting for a food distribution that takes place every evening, offering food to hundreds of migrants who are homeless or living in straightened circumstances in Trieste.

The migrants chat quietly to each other, as volunteers hand out bread and greet people who come regularly for the food on offer, laughing and joking with some they know well. Big urns are in place and volunteers arrive with reinforcements, unpacking stacks of piping hot breads, soups and stews to feed those waiting.

The day center can be found at Via Udine 19, Trieste.

Food distribution every evening in Trieste is operated by volunteers many of them working with Linea d'Ombra and Fornelli Resistenti (Resistance ovens), it takes place in the square in front of the central station, which has been nicknamed Piazza del Mondo (Square of the World) by the volunteers and the migrants who attend.

Read AlsoItaly: Migrants evicted from Trieste's Old Port area