The German government's attempts to usher in stricter migration policies are taking effect on various migrant groups in the country. Ukrainians are set to receive lower benefits in line with other asylum seekers, Afghans are finding it more difficult to gain protection in Germany, and the number of deportations has increased "significantly."

One of the German government’s main promises on taking office in May this year was to steer a tougher migration policy course than the previous social democrat-led coalition.

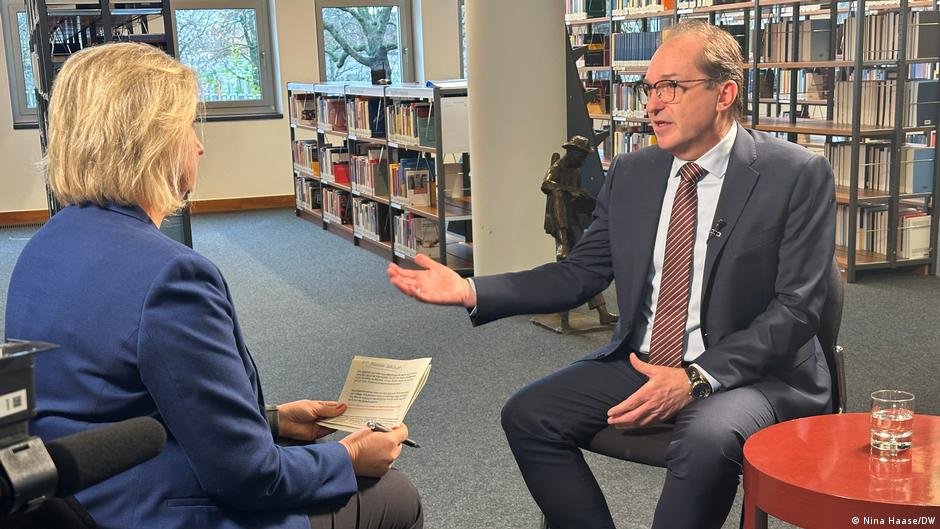

Last week, in an interview with Germany’s international broadcaster Deutsche Welle, German Interior Minister Alexander Dobrindt said that he wanted to crack down harder on what he termed "abuses" of the asylum law.

"My course is very tough," agreed Dobrindt. "From day one, we took the decisions needed to make sure that border controls are tightened, people are turned away, and family reunifications are suspended."

An overall drop in asylum applications by 60 percent, cites Dobrindt, is just one of the positive effects of his measures.

Read AlsoWhen protection fails: Why trainees in Germany are still being deported despite legal safeguards

A revolution in migration policy?

On the German Interior Ministry website, this new course is organized under the headline "Mit Humanität und Ordnung: Die Migrationswende", which translates to "With humanity and order: The migration [policy] revolution or change." The word "Wende" is often deployed in German not just to describe a small change, but a sea change, a revolution.

For instance, die Wende is usually used as a shorthand to describe German reunification and the fall of the Berlin wall, and to demark the time before and after 1989/1990. Politicians will also use the word when they want to underline that their approach represents something significantly different, a new era. In the last government, lots of politicians talked about die Energiewende --the energy revolution.

Under the current government’s own terms, the revolution appears to already be bearing fruit. Between January and October, 19,538 people were deported, around a fifth more than in the same time period in 2024, stated the German Interior Ministry, according to the financial newspaper Handelsblatt.

Read AlsoGermany: Skilled workers welcomed, as integration rules tighten

'Significant increase' in deportations

According to the tabloid newspaper Bild am Sonntag, deportations in the first ten months of 2025 represented a "45 percent increase" on the previous year. Germany’s Interior Minister Alexander Dobrindt reportedly told Bild "it is all about control, steering a tough course and marking clear boundaries in migration policy. We apply that to deportation and returns too. We will be continuing on this course, and we are also preparing to be able to deport people to Syria and Afghanistan."

On the Interior Ministry website, Dobrindt highlights his policy of increased border controls and the suspension of family reunification programs. Removing the fast track to residency, introduced by the previous government, is another policy measure the government has sought to remove, as well as increasing the list of countries considered to be "safe" by the German government, thus allowing for increased numbers of deportations to those countries.

Those convicted of serious crimes also have no right to stay in Germany, underlines Dobrindt. In July, a first flight with 81 Afghan nationals convicted of crimes took off and flew those on board back to Kabul. Since then, the German government has made efforts to talk directly to the Taliban authorities, rather than going through an intermediary like Qatar. They hope to operate more flights soon, promised Dobrindt, adding that Syrian nationals in a similar position, convicted of serious crimes, should also be sent back to their own country now that it has been almost a year since former dictator Bashar al-Assad fell from power.

Read AlsoMerz: It's time for Syrian refugees to "return home"

Family reunification suspended

Germany, underlines Dobrindt, is also keen to work with its European neighbors to "stem the flow of the numbers of those attempting to migrate irregularly towards Europe."

Being able to turn people back at the borders is another policy that Dobrindt has been keen to enact: "That way we can reduce the numbers illegally migrating to Germany and also act against the smugglers and traffickers too."

According to Dobrindt, smugglers have profited in the past from the idea that if you can get one family member to Germany, the rest of the family can then follow. That is why, says Dobrindt, he has been rethinking the family reunification program, removing the right to family reunification for those who only hold subsidiary or temporary protection status.

This, he hopes, will "destroy the business model of criminal gangs."

Read AlsoMerz says Europeans fear 'public spaces' due to migration

Reduction in benefits for Ukrainians

Changes in policy related to migration management also affect Ukrainian refugees: Last week, the government announced it would be reducing the amount that Ukrainian refugees in Germany can receive in welfare. This brings their potential benefits in line with all other asylum seekers, instead of offering them a higher rate, which will only be available to German citizens on welfare. Instead of 563 euros a month, Ukrainians who arrived after April 1 will now receive just 441 euros, as well as losing automatic access to healthcare, and being subject to stricter monitoring to ensure they accept employment when offered it.

This measure was announced less than a month after the German Interior Ministry estimated that around 1,000 young Ukrainian men were arriving in Germany every week, an almost tenfold increase from the 138 who were registered as having arrived in August, shortly after Ukraine relaxed the rules on men under 60 leaving the country. Previously, most adult men under 60 had been required to stay in case of being called up for the war effort in one capacity or another.

Since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, around a million Ukrainians have entered Germany and, like in the rest of the EU, were granted a special kind of refugee status. This meant they could travel freely back and forth to their home country, but were also provided with support in the form of accommodation and welfare benefits where needed.

Increasingly, as the war progressed and budgets tightened, this policy has been seen critically by many, not least by other groups of asylum seekers who felt it was unfair that Ukrainian refugees should be treated differently from them.

Out of the almost one million Ukrainians in Germany, the Interior Ministry says that around 672,000 of them receive social benefits. Between April 1 and September 30, 83,000 Ukrainians entered Germany, and 28,000 of these applied for social assistance.

Read AlsoGermany’s interior minister proposes sharing deportations among EU states

Welfare and integration

One Ukrainian, interviewed by AFP, told the news agency that she worried that withdrawing the assistance would lead to worse integration and outcomes. Alla Dudka, a 57-year-old from Odesa, said she received benefits from the German state for about two-and-a-half years. Now, Dudka said she works part-time as a charity worker. "From my own experience, I know that this initial support does not lead to dependency, but rather makes integration possible in the first place," Dudka told AFP.

Other Ukrainians, such as a new 20-year-old arrival Timofiy, who arrived in Berlin in November, told AFP that he believed some Ukrainians had been taking advantage of German government generosity, and had not sought to work or become independent. "I would like to be able to work…" Timofiy told AFP, "and stay and live in Germany if possible."

Read AlsoCriticism over German government plan to indefinitely detain migrants to be deported

Criticism from the opposition holds government to account

This week, the opposition Green party raised criticism over Dobrindt’s strict course concerning the admission of Afghan refugees.

Around 1,800 Afghans remain in Pakistan, waiting for the final permissions to fly to Germany, after having been accepted as part of a German evacuation program under the previous government.

Last week, another 52 Afghans arrived and 62 people were reported to have accepted a German government cash offer to withdraw from the program altogether. Those remaining are worried that if they are not able to fly to Germany before the end of the year, they will be subject to deportation orders in Pakistan and forced back to Taliban, where many claim they would face danger, if not certain death.

Green politician and parliamentary group leader Irene Mihalic called for a special meeting about the issue, which is due to take place on Wednesday (November 26) in the morning, reported the German weekly news magazine Der Spiegel.

"The Interior Minister needs to be clear about what will happen to those who have been cleared to come to Germany, but have not yet received their visas or flights," said another Green politician, with a special focus on interior affairs, Marcel Emmerich, reported Spiegel. "This needs to be done before these families are threatened with deportation from Pakistan," added Emmerich, saying that this was likely to happen "before Christmas."

Dobrindt told DW last week that all Afghans with permission to enter Germany would be brought to the country by the end of the year.

Mihalic added that Dobrindt also needed to explain to MPs just why "the government had put the brakes on issuing the visas and flights, and why the government had also apparently ignored court decisions, which had found that the government had to honor the permissions issued under the previous government."

Some of those waiting in Afghanistan for flights to Germany worked for the German military or government organizations, others are part of a program for those particularly at risk in Afghanistan, including judges and human rights workers and their families.

Read AlsoGermany: Stricter asylum rules, deportations and rollback of fast-track citizenship