The Chamber of Commerce for Milan, Monza, Brianza and Lodi in northern Italy is running a pilot project entitled Integra, and operated by Formaper. In collaboration with eight business associations, the chamber of commerce is offering job-focused training to migrants to allow them to enter the job market in sectors that are crying out for staff.

Bouchra, Henock and Upa are smiling. Not only have they graduated from their training courses, but they are some of 130 people who have found work after completing targeted training via a new project entitled Integra.

Operated by the company Formaper, Integra is an initiative created and funded by Milan’s Chamber of Commerce -- Italy’s largest chamber of commerce. Apart from Milan, it is also responsible for the nearby Lombardian towns of Monza, Brianza and Lodi.

Italy’s northern regions, particularly Lombardy, where Milan is the regional capital, and Friuli-Venezia Giulia, can be described as Italy’s economic and industrial powerhouses. But, mostly due to demographics affecting much of Western Europe, many companies operating in diverse sectors are facing a shortage of labor.

The Italian National Statistics Institute (ISTAT) published its latest workforce predictions up until 2050 on October 21. The statisticians highlight that Italy's population is aging, and the population considered economically active (between 15 and 64) is diminishing. This not only reduces the potential workforce, but is a drain on the welfare system too, as more people expect pensions and fewer people are working to replenish the coffers.

ISTAT predicts that more people in Italy will have to stay in employment for longer, a trend that is already happening, and more of those who might be currently inactive (for instance, a greater proportion of women) will have to enter the workforce. But migrant labor, via regular routes, would also be important to balance the demographic trends, according to ISTAT.

Read AlsoItaly: More migrant workers needed, says top business association

In the next five years, an additional 640,000 workers could be needed

In a promotional video for the Integra project, Milan’s Chamber of Commerce estimates that in the next five years, as many as 640,000 additional workers could be needed. That, they say, is equivalent to 21.3 percent of the total national labor demand.

According to data for 2024, gathered by the Italian Observatory of the Job Market and the platform InfoJob, the region of Lombardy already accounts for about 29.1 percent of job offers on the Italian market, so a little under a third of those nationwide.

And this is where the Integra project is hoping to come to the rescue. It focuses on handpicking migrants, asylum seekers and refugees, who have a desire to work but may have been blocked from entering the labor force. It offers them vocational training, over the course of a month or two, and then helps match them to jobs.

"Some of them might be stuck receiving benefits when they could be working and want to be working. Our course is designed to give them a hand towards that goal," explains Elena Marinotti, Senior Project Manager at Formaper, Milan Chamber of Commerce.

"To run this kind of project, we needed to create very strong regional alliances," continues Marinotti.

"So, the eight business associations representing different skills, professions and companies are part of this network. For instance, the association of artisans, or a confederation representing logistics companies. Then we have four big NGOs supporting migrants in the third sector, as well as the local municipalities, and the unions."

"Many of these organizations already run services to support job seekers, and so we utilized those and their networks to see which people would most benefit from our program. The union then offers a support desk and advice for participants on the scheme who might need help with bureaucratic issues once they are hired by the companies. Lastly, we have employment agency representatives on our board, so they are able to give us a hand with finding jobs for the trained people once they have completed their courses," adds Marinotti.

Read AlsoItaly passes decree against illegal employment of foreigners

258 migrants trained, 129 have jobs

Since the project’s start in February 2024, to date, 258 migrants have been trained and have gone on to take part in 244 job interviews. 130 participants have been hired.

Forty-year-old Bouchra Lamdihine is from Morocco and is one of the successful examples of the way Integra works. In a video for the project, Lamdihine explains that she took part in a tailoring course with Integra. "I did a two-year tailoring course in Morocco in 2015," explains Lamdihine, "but since then I hadn’t sewn." That is, until she began the tailoring course with Integra.

As a result of the Integra experience, Lamdihine was matched with work in a tailoring workshop and continues to work there today. "I learned so many skills," says Lamdihine.

Similarly, Henock Ndjoku, also 40, and originally from the Congo, has finally turned a run of temporary unskilled jobs in construction into a more stable employment contract at a big construction firm.

Ndjoku did the basic masonry course via Integra and now works at the company Teicos. "Before the course," recounts Ndjoku, "I worked lots of manual jobs in construction, but I wanted to get a professional qualification. Now I did a training course to become a builder. I learned how to use the work tools and materials, how to operate a cement mixer, and how to build a wall."

Read AlsoItaly: Project in Palermo offers training and jobs for migrants

From maths teacher to hotel laundry

Finally, there is Uthpala De Silva. "Everyone calls me Upa, I am 50 and I’m from Sri Lanka," says Upa in the promotion video for the project. "I have three children and I live with my children here."

Upa explains that she used to be a maths teacher back in Sri Lanka, but in Italy, she has taken a course to re-enter the job market in a very different sector. Following the course, Upa was offered work with Milan’s Grand Hotel, working in the laundry department. "This is a novel experience for me, I am very happy," says Upa, industriously ironing, steaming and pressing white linen at the hotel.

The training courses, explains Marinotti, generally last 100 hours and are intensive. "We offer such an intensive course, because many migrants can’t manage to sustain a much longer period of time. If we asked them to train for much longer, they might find unqualified work much more quickly and drop out of the course because they need to earn a wage as quickly as possible."

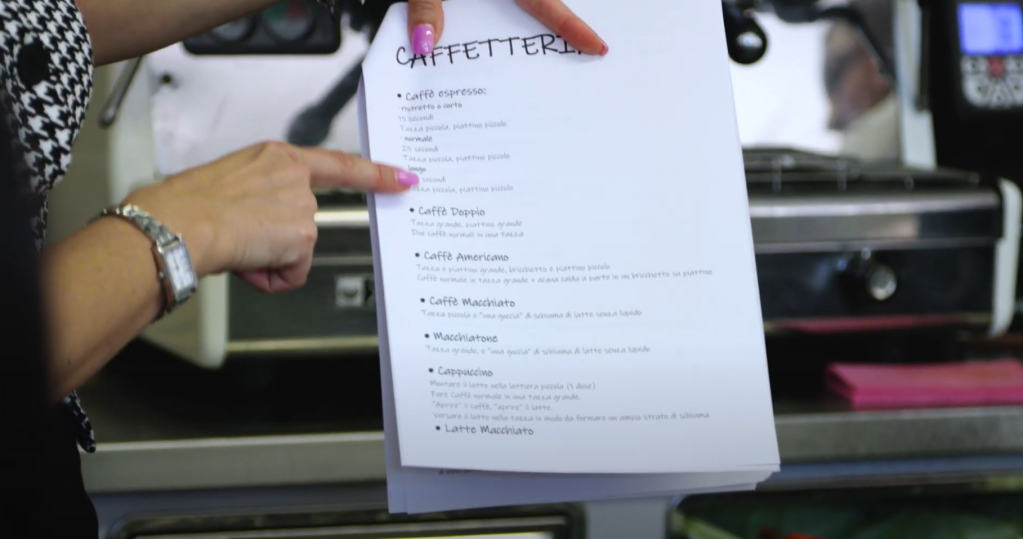

On offer at the moment are courses in hotels and hospitality, manufacturing, craft and construction, tailoring, gardening, mechanics, plumbing, electrician’s assistance, receptionist, logistics and shelf stacking. "We have special courses tailored to Milan’s needs, too. Here, the technical graphics industry and industrial printing are very big, so we had a course for workers who wanted to find jobs in that sector."

Read AlsoItaly: Study examines migrants and employment in Puglia

'We work with individuals'

Marinotti underlines that each course and each application is tailored to the individual. "We don’t work on mass hiring objectives. We work with individuals and try and find each person something that really works for them. We ask that people have a high standard of Italian. Mostly because that is what companies want, but also in order to follow the lessons, for instance the safety briefing, the technical competences, which are all taught in Italian, they need to be able to understand the language well."

Motivation is another factor that the organizers are looking for. As part of the course, they try and prepare candidates for job interviews, how to dress, the kinds of things that might be expected and asked about, but being able and willing to do the job for which you are trained is one of the most important factors, thinks Marinotti.

There have been some challenges along the way. Despite the selection process, Marinotti says that they discovered that one young and very promising candidate had managed to go through the training without it being discovered that she was actually illiterate. "She spoke really good Italian," remembers Marinotti. "But she was training to be a kitchen assistant, and at one point she was put on a station where she needed to be able to read the food choices to carry out her job, and we realized she couldn’t."

Because of her motivation, Marinotti said that the company where she was working found a station where she could work without needing to read, and she is now working on that part of her skill set, to make sure she can progress in future.

Read AlsoMigrant workers in southern Italy continue to face exploitation, MEDU warns

'You have to stay flexible'

You have to stay flexible when administering this project, laughs Marinotti. "Sometimes someone’s permits will run out and need to be renewed. Or perhaps someone is in a reception center and has to return by a certain time every evening but has been asked to do a night shift. So, our job requires a certain agility and fast problem solving to try and remove all the blocks that might appear on the path of a migrant trying to obtain and hold down a job."

"But that is the beauty of this project, because we are financed by the chamber of commerce we can keep responding to these bumps and making it happen, which is really rewarding for us."

Marinotti says she hopes that at the end of the pilot phase in 2026, they might be able to scale up the initiative and make it structural. They have also had interest from other chambers of commerce in other regions.

Read AlsoItaly's Sant'Egidio: Work corridors initiatve in Africa

Scaling up?

So far, people from 38 different countries have passed through the project. The majority came from Peru, Egypt and Ukraine. But there have also been candidates from various sub-Saharan African countries, Bangladesh and Pakistan.

Some people who join the project have a very high standard of education, but the majority have a very basic amount of schooling. Women represent 40 percent of course participants, and men 60 percent.

Another challenge for the future is that the basic skilled jobs are changing. A few years ago, everyone was keen on being a car mechanic; they might have had experience of fixing engines in their home country. But today, mostly car mechanics need to be computer and mechatronic experts, so the skill set has become very different.

Companies in general are looking for greater and greater skill sets and educational levels, even to fill some of the most basic jobs. This is not just affecting migrants but young Italians too. The expectations are now very high, thinks Marinotti.

Nevertheless, Milan’s Chamber of Commerce judges its pilot to be a continuing success, underlining that "where there is training, there is a future."

Read AlsoItalian study: Integration pays off as migrants add value to society