Bavaria’s economy needs workers, but its bureaucracy and deportation policies often push them away. InfoMigrants spoke with employers, refugees, volunteers and officials to explore how the state is trying to bridge the gap.

Nestled on a forested hillside just outside Munich, the beer garden at Mariabrunn feels a world apart from bureaucracy and policy debates. Wooden tables and benches huddle beneath towering trees; roots spiral across the earth. If you climb to the clearing above, the view opens onto the sprawl of Munich and, on clear days, the jagged outline of the Alps beyond.

Behind the counter, Hassan Hedayati, originally from Afghanistan, pulls beers and serves Steckerlfisch (smoked mackerel) with potato salad -- chatting in a warm Bavarian accent with customers. Next to him stands Manfred Valentin, his boss, in a blue-and-white checkered shirt, smiling broadly as he helps pour mugs and tidy tables.

"Hassan came here years ago," Valentin tells InfoMigrants. "He learned everything on the job. He’s reliable, quick, and gets along with everyone. People like him."

"At first it was hard – the language, the rules," Hedayati recalls. "But people helped me. My boss trusted me. Now this feels like home."

Hedayati arrived in Germany around 2016 and first worked as an apprentice chef before starting his full-time position here. He has a valid work permit and plans to stay in Germany long-term, however, his stability stands in contrast to many others whose futures remain precarious. Bavaria now finds itself straddling a tension: a region in desperate need of workers, yet entangled in rules that make hiring -- and staying -- difficult.

Read AlsoRefugees in Germany: Many still at risk of poverty

A growing labor gap

Bavaria’s business associations and economic researchers warn that the state, much like the rest of the country, is in the grip of a widening labor shortage.

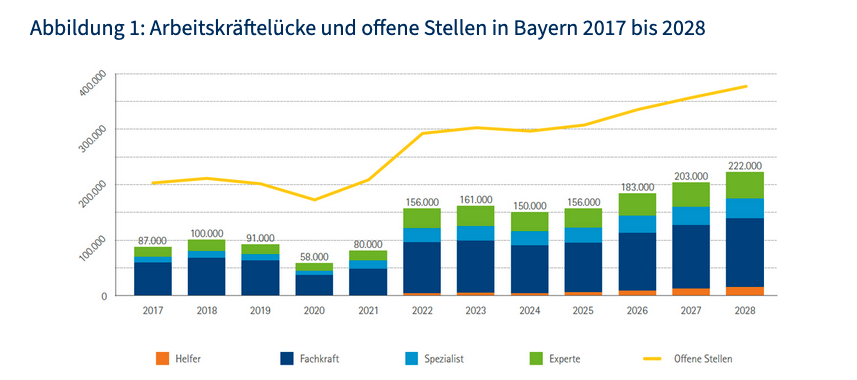

According to the Institut der Deutschen Wirtschaft (IW Köln) and the IHK München, Bavaria faced a workforce shortfall of around 161,000 people in 2023, projected to rise to over 220,000 by 2028 if current trends continue.

That gap translates to over half (roughly 53 percent) of open positions lacking qualified candidates -- this means that more than half of all jobs cannot be filled from existing labor pools.

Without this shortfall, the state’s economic output in 2028 would be about 24 billion euros higher, according to IW forecasts.

The deepest shortages are expected among skilled workers with vocational training -- around 120,000 missing positions -- followed by specialists, experts, and lower-skilled roles. For many employers, the trend is already visible: in small workshops, restaurants, and care facilities, positions stay open for months.

Read AlsoTen years on: Refugees near German employment levels

Existing work, limited access

"There’s plenty of work," Valentin says. "But as an employer, you have to make sure everything is legal. If the paperwork isn’t right, you risk fines. So some businesses just avoid hiring refugees altogether. It’s crazy -- we need them, but the system scares us off."

"For me, it’s simple," he tells InfoMigrants. "If someone works hard, speaks the language, and wants to stay, we should make it possible. Sending trained people away helps no one."

While the jobs exist, both refugees and employers are often trapped in a web of rules and delays.

"Many of those who could fill these roles are already here," says Nanette Nadolski from the support group Helferkreis Weichs. "They’ve been trained, they speak German, they’ve proven themselves. But their residence papers expire, or they wait months for renewals. Employers get nervous and step back."

She describes a recurring cycle: someone completes training, lands a job, and then faces long delays renewing their permit.

"It’s exhausting," she says. "The bureaucracy wears everyone down -- the refugees, the employers, and us volunteers too."

Read AlsoSkilled migration to Germany: Navigating the challenges

'Too many' or 'poor management'

During an interview with InfoMigrants, Bavaria’s Interior Minister Joachim Herrmann claimed that the state was "at times overwhelmed" and that "too many refugees" came to the region.

Yet NGOs and volunteers challenge that assessment.

"What is ‘too many’?" asks Jana Weidhaase from the Bavarian Refugee Council. "People have always moved. The question is how we manage it. Overcrowding and friction are self-made problems -- a result of rigid structures, not of people."

For Weidhaase, the real barriers are administrative.

"At the beginning, asylum procedures often took over a year," she explains. "Even now, foreigners' authorities are overburdened. Refugees and employers face long waiting times and unclear rules -- every work permit requires new paperwork, new checks, new delays."

Despite the labor shortage, asylum seekers must still wait six months before being allowed to work. Even then, employers must navigate complex approval forms.

"It’s not that there’s no work," Weidhaase says. "The barriers are man-made."

"Sometimes two different offices give two different answers for the same case," she notes. "It’s not just slow -- it’s inconsistent. That uncertainty keeps people from planning their lives."

Read AlsoGermany: Study finds a quarter of foreigners wish to leave – except asylum seekers

The bureaucratic burden

Speaking to InfoMigrants, Nadolski describes the frustration that now defines much of her work. "People wait almost six months just to renew a residence permit," Nadolski says. Some municipalities have introduced rules and processes that can further complicate the situation. "They get a temporary document that allows them to keep working -- but it has no name, no date of birth, nothing identifying the person. Employers see that and say, ‘I’m not taking that risk.’"

What began as an emergency response has hardened into routine administration, she explained. "It discourages people," she adds. "And it discourages companies too."

Yet while bureaucracy slows many refugees down, Bavaria’s economy can’t afford to lose them. According to the Bavarian Chambers of Commerce (BIHK), the state could face a shortage of more than 220,000 skilled workers by 2028. In 2024 alone, the labor gap was already over 110,000 unfilled positions.

Many refugees who started apprenticeships after 2015 now fill those positions, but uncertainty continues to haunt them. "People who have jobs or training offers are still being deported," Nadolski says. "And at the same time the government says we need workers from abroad. It doesn’t make sense."

Read AlsoWhy Germany struggles to attract African skilled workers

Policy and paradox

The Bavarian government has also acknowledged the need for more skilled immigration and efforts to accelerate legal pathways – including faster recognition of qualifications and shorter waiting times

However, Herrmann also insists Bavaria is balancing necessity with control:

"We have to maintain public confidence -- including deportations when there is no legal right to stay," he says. "At the same time, we are supporting those who are working legally and contributing."

In 2024, Bavaria oversaw 3,010 deportations -- an increase of 27 percent from the previous year -- and recorded around 15,000 voluntary returns, about 26 percent more than in 2023.

According to the Landesamt für Asyl und Rückführungen (LfAR), deportations primarily target criminals and those who pose a security risk. But advocates argue that many affected are working, paying taxes, and contributing to the local economy.

"Work doesn’t protect you from deportation," says Weidhaase. "Employers invest in people, train them, and then see them sent away. It breaks trust -- and it makes no sense economically."

Read AlsoGermany: Stricter asylum rules, deportations and rollback of fast-track citizenship

Volunteers as connectors?

Local volunteer groups believe they could help bridge this divide.

"We know who’s motivated, who already speaks German, who fits well in a team," says Nadolski. "But officially, we’re not part of the process."

Oda Füser, coordinator of the Helferkreis Haimhausen, agrees:

"People want to contribute. There’s no shortage of motivation -- only of paperwork and trust. The bureaucracy doesn’t always talk to itself. That’s where things get stuck."

Dorte-Freyja Werner, a German language teacher who has worked with refugees, tells InfoMigrants that small efforts often make a big difference. "When someone gets a job, it changes the whole mood," she says. "They have purpose again – it’s not just about money."

Artist and organizer Paul Huf says he sees the same pattern across Munich. "We talk about ‘integration,’ but it’s really about participation," he says. "When people work or play sport together, politics fades into the background."

Read AlsoIntegration to emigration: Why do migrants leave Germany?

Back to Mariabrunn: Work, dignity, and continuity

In the afternoon light, Mariabrunn’s beer garden hums with customers. Hedayati wipes down the counter, laughing with Valentin. Out of the forest hush, voices and the clinking of glasses fill the air.

For Hedayati, this place is more than a job -- it’s a home rebuilt. For Valentin, it’s a business sustained by capable hands.

This scene captures an idyll -- both of Bavaria and of how migration can foster economic vitality and social cohesion. Yet it is, of course, not always that simple.

Beyond this pocket of calm, Bavaria is wrestling with deeper questions: how to reconcile its labor needs with its migration policy, and how to resist the political currents that turn workers into scapegoats. As debates harden and far-right parties gain ground, the gap between economic reality and political rhetoric only seems to widen.

"Germany gave me a chance," Hedayati says. "Now I just want to give something back."

Read AlsoTen years since the 2015 migration movements (4/5): Munich between promise and pressure