Ten years ago, the image of Syrian toddler Aylan Kurdi’s lifeless body on a Turkish beach shocked the world and rekindled the debate over Europe’s treatment of migrants as thousands fled the Syrian war. A decade later, InfoMigrants returns to the places marked by this unprecedented arrival of migrants. The city of Munich, ten years after Germany opened its doors to refugees, shows both the strain and the strength of that choice. Between politics, paperwork, and daily acts of solidarity, residents and newcomers continue to define what "We can do this" really means.

On a crisp autumn morning, the platforms at Munich’s central train station are busy with commuters and tourists. Coffee cups in hand, people hurry past the glass doors where, 10 years ago, hundreds of volunteers once stood waiting with food and clothing. In September 2015, as thousands arrived from Austria, the city became the face of Germany’s "open-door moment" -- and the world watched as volunteers and heavy security welcomed exhausted families stepping off trains.

Back then, the response wasn’t led by institutions but by ordinary citizens. Across Bavaria, people formed "Helferkreise" -- local volunteer groups that helped new arrivals find housing, clothes, and German classes. Some gave up their jobs or reduced their working hours to keep the effort going.

A decade later, the banners are gone, the news cameras have moved on, and the people who stayed are now part of the city’s quiet routine.

Germany’s promise -- “Wir schaffen das,” or “We can manage this” -- was never just about numbers or borders. It was about a society deciding whether compassion could survive the grind of bureaucracy and politics. In Munich, that question is still being tested every day.

Read AlsoThe 'refugee summer' of 2015: Key moments that shaped Germany

The bureaucracy 'beast'

Speaking to InfoMigrants, Nanette Nadolski from the Helferkreis in Weichs near Munich, who has supported refugees in Bavaria since 2015, described the frustration that now defines much of her work. "People wait almost six months just to renew a residence permit," Nadolski said. "They get a temporary document that allows them to keep working -- but it has no name, no date of birth, nothing identifying the person. Employers see that and say, 'I’m not taking that risk.'"

What began as an emergency response has hardened into routine administration, she explained. "It discourages people," she added. "And it discourages companies too."

Business groups warn that Bavaria’s labor shortage is worsening. A 2025 report by the Bavarian Chamber of Industry and Commerce (BIHK) found that around 160,000 workers are currently missing across the state, a number expected to rise to more than 220,000 by 2028. The study, by the German Economic Institute (IW Köln), estimated the annual economic loss at 24 billion euros. BIHK director Manfred Gößl said migration now plays a "decisive role" in sustaining Bavaria’s workforce.

Many refugees who started apprenticeships after 2015 now fill those positions, but uncertainty continues to haunt them. "People who have jobs or training offers are still being deported," Nadolski said. "And at the same time the government says we need workers from abroad. It doesn’t make sense."

Read AlsoWhy Germany struggles to attract African skilled workers

arrived at the station in southern Germany on Sept. 5 and 6 from Austria aboard special trains arranged

to manage the refugee crisis | Photo: Imago

A political divide

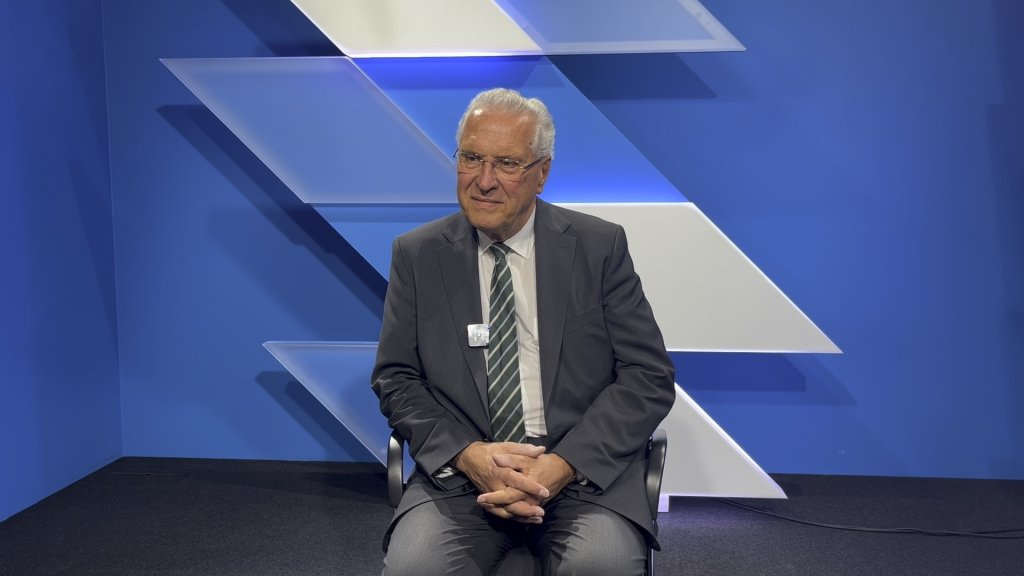

Bavaria’s Interior Minister Joachim Herrmann told InfoMigrants that the state’s approach remains guided by two priorities: security and order. "We have to maintain public confidence," Herrmann said. "That means enforcing the law consistently, including deportations when people have no legal right to stay."

According to figures from Bavaria’s Landesamt für Asyl und Rückführungen (LfAR), deportations under Bavarian jurisdiction rose by more than 27 percent in 2024, reaching 3,010 cases. The agency also recorded a record 14,757 voluntary returns -- around 26 percent more than the previous year. LfAR President Axel Ströhlein said the increase reflected "close and effective cooperation between all authorities involved," noting that removals continued to prioritize convicted offenders and individuals classified as security risks.

Nationwide, deportations have also climbed. A recent Diakonie report found that more than 20,000 people were deported across Germany in 2024, up from about 13,000 in 2022.

Herrmann emphasized that "the majority of asylum seekers live here peacefully," but insisted that citizens "expect rules to apply to everyone." That position resonates with parts of the electorate but contrasts with the daily experience of many local initiatives.

Oda Füser, from the Helferkreis in Haimhausen, a small town municipality just outside of Munich, explained that while civic engagement remains strong, the public mood has shifted. "Back then, everyone was helping," she said. "Now, many people still do -- but they’re tired. There’s fear about security, about costs. Yet Munich and Bavaria are very safe places. People forget that."

For Harald Friesner, a Munich police officer who also volunteers with the group The Long Run, the tension is visible from both sides.

"People sometimes forget how much the city has done," he told InfoMigrants. "Yes, there are challenges -- housing, paperwork, integration -- but Munich is still one of the safest cities in Germany. Most people just get on with their lives."

Official figures show: Bavaria recorded 4,218 crimes per 100,000 inhabitants in 2024, a 3.3 percent drop from the previous year. Munich continues to rank as Germany’s safest large city.

Read AlsoGerman study: Immigration does not raise crime rate

What is 'too much'

In his interview with InfoMigrants, Herrmann repeatedly stated the number of refugees in Germany remained "too high" and claimed that municipalities were "under serious pressure."

"We’ve reached a point where we can’t just keep taking more," Herrmann said. "There has to be a limit, and we must ensure that those without a right to stay leave the country."

But many of those working on the ground disagree. Nadolski rejected the idea that Bavaria was overwhelmed.

"We haven’t received new arrivals for more than a year," she said. "And yet politicians keep talking about overload. That’s simply not true."

Füser agreed, warning that such language shapes public perception. "People hear that and start to believe it," she said. "But when you look around, there’s work, there’s housing, and most people who came here years ago are working or in training. The fear doesn’t match reality."

Jana Weidhaase from the Bavarian Refugee Council said claims of overwhelm misrepresented the real issue.

"The system is under pressure," she told InfoMigrants, "but not because of the number of people. It’s because of how complicated the bureaucracy has become."

Read AlsoBig hopes and harsh realities: How migration shaped Germany

From crisis response to daily work

In 2015, volunteers stepped in where institutions struggled. Weidhaase told InfoMigrants that those early months "showed what a community can achieve when politics lags behind."

"People gave up their evenings and weekends to help," she said. "But over time bureaucracy took over. The process became more complicated instead of simpler."

Weidhaase said her organization now spends much of its time fighting deportations of people who have completed training or have jobs. Such cases, she warned, "undermine trust in the system." During the first years, flexibility often replaced red tape. "We realized it made sense to bring people into work and training," Nadolski said. "For a time, that worked surprisingly well." But as rules tightened, many of those gains slowed or reversed.

Read AlsoGermany: Deportations are on the rise

A city transformed

A decade later, Munich has changed visibly. Arabic, Dari, and Ukrainian mix with Bavarian dialects in markets and playgrounds. For some residents, that diversity feels natural; for others, unsettling. "You can feel the tension," Füser said. "But you also see that life has moved on. Children who arrived in 2015 are now finishing school, speaking fluent German, planning apprenticeships. That’s part of Munich now."

Still, fatigue persists. Volunteers like Füser and Nadolski describe dwindling motivation after years of navigating a complex system. "The motivation is still there," Füser said, "but the bureaucracy kills it. Even small things take endless time."

Read AlsoThe 'refugee summer' of 2015: Key moments that shaped Germany

Art, sport, and small victories

Artist and community organizer Paul Huf told InfoMigrants that creativity helped where politics stalled. "Art and sport put people on equal footing," he said. "On the field or in the studio, background doesn’t matter."

He remembers standing at the central station that night in 2015. "I had tears in my eyes," he said. "It felt like a new beginning." A decade later, he runs The Long Run, an organization that brings together refugees and Munich residents through sports, as well as offering additional support including administrative and practical assistance. "The bureaucracy has grown," Huf admitted. "Half my time is spent dealing with permits. But when you see friendships form, you realize it’s worth it."

Read AlsoBuilding new lives in Germany: Volunteers empower migrants

New citizens

Uday Alturk, who arrived from Homs, Syria, in 2014, now works as a driving instructor and recently received German citizenship. "When I first saw the city from the plane, everything looked so green and organized," he told InfoMigrants. "At first I missed my friends, but my family was here. And family means home." Alturk learned German through YouTube videos and playing football with people he met in his local neighborhood in Munich.

Later, he joined a choir that performed around the city and later the whole country. "Through music and sport, I met people," he said. "Now I feel completely at home." Alturk is planning on opening his own driving school soon. He’s also built a following on TikTok, where he shares short videos with driving tips and advice for new learners. "We work, we contribute, we pay taxes," Alturk said with a smile. "That’s integration -- or whatever you want to call it." Germany naturalized almost 292,000 people in 2024, the highest number on record, many of them Syrians who arrived during the 2015 migration movements.

Read AlsoTen years on: Refugees near German employment levels

Fatigue and persistence

According to data from the Bavarian Refugee Council, legal support groups in the region now spend most of their time appealing deportations or resolving work permit issues. Weidhaase said the workload has nearly doubled in recent years. "Many of these cases involve people who have jobs, who pay taxes, who have children in school," she explained. "When they receive deportation orders, it breaks trust in the system."

Weidhaase said that while new arrivals have slowed, the complexity of existing cases has increased. "There’s less chaos now," she said, "but much more bureaucracy." Despite the fatigue, she sees signs of progress. "The majority of people who stayed are working or studying," she noted. "That’s an achievement -- not because of the system, but because of perseverance."

Read AlsoHelping women refugees in Germany find work

Between everyday life and politics

At the state level, political rhetoric has hardened. Officials speak of enforcement and control; deportations from Bavaria rose by about 27 percent in 2024. Yet in daily life, Munich’s coexistence continues with little friction. Cafés and beergardens in the city center employ staff from Syria, Ukraine, Afghanistan and other countries. In schools, special language programs and dedicated "welcome classes" help children adjust to the curriculum and find their place among classmates.

In the heart of the city, the cultural center Bellevue di Monaco hosts language exchanges, workshops as well as a range of sports on its rooftop for locals and newcomers with spectacular views of the city.

"Munich is doing well," Nadolski said. "But Munich is not all of Bavaria. In smaller towns, it’s different." The contrast between official policy and local practice is sharp. Bavaria’s government stresses discipline; its citizens often rely on pragmatism. Füser said, "Munich found its own way. People helped because they couldn’t imagine doing nothing."

Read AlsoGermany: Government keen to cap protection rate as 1 in 25 people now has refugee status

The legacy of 2015

As evening falls, trams glide past the central station, carrying office workers home and students out for the night. Nothing about the scene hints at the upheaval that once began here.

But the legacy of 2015 lives in countless small interactions: a shared meal, a language exchange, a football match. Ten years on, Munich’s story is less about the arrival than about the efforts that followed. It is about the slow, unglamorous work of people who kept showing up -- and a city that, despite fatigue and contradiction, never quite let go of its promise.