In a bid to increase the transfer of asylum seekers slated to be deported under the Dublin Regulation, Germany is testing special return centers for this purpose. They have been criticized by migration policy experts, activists and asylum seekers for placing people under more strain while failing to streamline the deportation process. InfoMigrants visited Eisenhüttenstadt, where one such center is located.

German authorities opened two so-called 'Dublin centers' in the northern city of Hamburg and in the eastern town of Eisenhüttenstadt, near the Polish border, earlier this year. They are meant to help speed up the return of those migrants who are slated to be deported under the Dublin Regulation, an EU law that determines the country responsible for processing a person’s claim for international protection in Europe.

In June, people staying at the Eisenhüttenstadt facility wrote an open letter to the public that drew attention to the centers and raised alarm among rights groups.

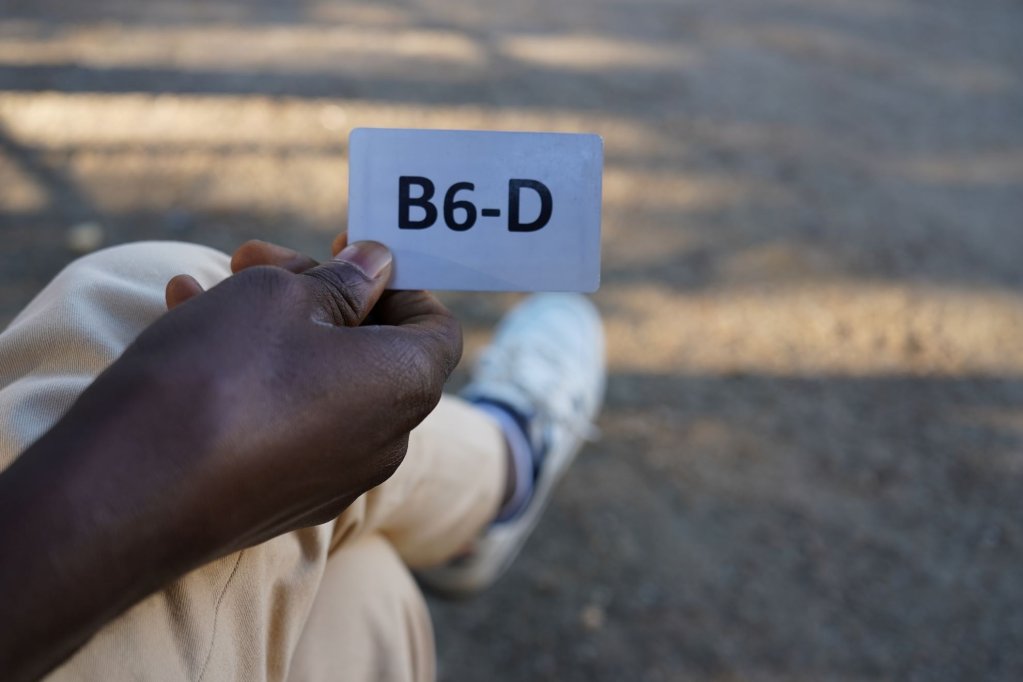

"On our Plastic Card is a 'D' that stands for 'Dublin'. Everybody knows that we are the future Poland deportees. We are treated differently from the others in camp. We feel segregated in the Dublin-Camp. It is shameful for us," the letter said.

Further measures to restrict movement

Concerns about the centers have increased since Germany’s cabinet adopted two bills last month with additional possibilities for more stringent asylum procedures. These include giving federal states the option of setting up more Dublin centers, and restricting the movement of people with negative asylum applications. The bills have yet to be discussed in parliament.

"There is a big policy debate about establishing similar centers across Germany," said Wiebke Judith, legal policy spokesperson for ProAsyl, a German asylum rights organization.

"We are worried about having more and more centers that do some kind of segregation according to status," Judith said in an interview, noting a shift towards more restrictive housing.

"The more people are segregated, the more they are put under mental stress."

Read AlsoGermany moves to implement EU asylum reform

Dublin rules

Under Dublin rules, asylum seekers are meant to file their application in their first European country of arrival, which is usually along the European Union's external borders, such as Italy or Poland.

Germany, which is entirely surrounded by Dublin signatories, made the highest number of Dublin transfer requests last year, according to Eurostat. But less than 8 percent of around 74,500 requests resulted in deportation, reflecting a general EU-wide gap between requests and transfers that has stoked criticism from all concerned parties.

The gap is due to the reluctance or refusal of some EU members to take back asylum seekers. Courts sometimes block deportations due to concerns about reception conditions in the country of return.

In Germany, bureaucratic delays can make it difficult to meet the deadline of six to 18 months for transferring a Dublin case, after which German authorities must handle the application, policy experts say.

"The central accommodation makes it easier to keep track of the persons concerned and simplifies procedures such as delivering notices of decisions regarding their case," the previous government’s Interior Ministry said in a statement in February.

The return centers are also intended to ensure Dublin cases do not receive regular asylum seeker state benefits, it added.

'The idea is to lower the standards'

Critics, including rights groups, activists and asylum policy experts, said placing Dublin cases in separate, and potentially more restrictive, accommodation mainly worsened the situation of already vulnerable people.

"I don't think it will be doing very much, very honestly. I think it's symbolic politics. This is really just to show that something is being done," said Bernd Kasparek, a migration and border researcher with Berlin’s Humboldt University.

Eleonora Testi, a senior legal officer for Brussels-based European Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE), said the Dublin centers were “one of the classic deterrence policies” being put in place across Europe.

"The idea is to lower the standards as much as possible," she said in an interview, noting similar approaches in Belgium and Sweden.

Hamburg center -- 'too early for an assessment'

The first Dublin center in Hamburg, which is located in the reserve hall of an arrival center, accommodates people forcibly required to leave Germany and is intended to prepare for their deportation -- ideally within two weeks.

By the end of August, 75 men had been housed at the center, of which 38 were transferred to another European country, the press office of the Hamburg Department of Interior Affairs told InfoMigrants.

Those staying in the Dublin center only receive in-kind benefits for daily needs, along with 8.85 euros every two weeks to cover additional hygiene items.

"It is still too early to make a final assessment," the spokesperson said via email. "However, initial positive developments are emerging, for instance, regarding improved procedures and coordination."

'Evidence of the utter dysfunctionality of European legislation'

In Eisenhüttenstadt, the Dublin center is a separate building within a large general reception center. It focuses on asylum seekers who have already applied for international protection in neighboring Poland. These cases are identified through a centralized biometric database, Eurodac, which stores the fingerprints of asylum applicants across the EU.

The idea is to accommodate such individuals from the moment they arrive in Germany and throughout the whole Dublin review process, rather than at the end of their assessment.

"That makes the center in Eisenhüttenstadt a model for all the other federal states to follow," the Information Ministry’s statement said.

But the head of the Eisenhüttenstadt center, Olaf Jansen, told InfoMigrants the system had not been "very impressive" so far. Of 75 people accommodated in the center since March, only five were deported to Poland, four of whom returned to Germany and reapplied for asylum.

"The instrument is far from being effective and another evidence of the utter dysfunctionality of European legislation," Jansen said via email. "Before Dublin centers can be scaled up, there needs to be new legislation that makes sure that a return decision can be executed and is respected. As long as this is not the case, Dublin centers do not make any difference."

Read AlsoGermany expands Dublin deportation centers

Local protests in Eisenhüttenstadt

On a grey September afternoon in Eisenhüttenstadt, a sleepy depopulated industrial town, a group of activists gathered on a stretch of grass outside the gate to the general reception center. As part of a tour to raise awareness about migrant rights, the group had planned a small afternoon concert, speeches and a cooked meal.

They brought a bouncy castle for children staying at the center, set up a stage, and hung up banners denouncing border clampdowns and asylum policies. "No Dublin Centers in Eisenhüttenstadt", said one yellow canvas sign, swaying in the wind.

"The center is a problem," said activist Fawzi Al-Dubhani, who is part of a small association that supports refugees and asylum seekers in Eisenhüttenstadt. He noted that people staying at the Dublin center were not allowed to leave their rooms at night, when deportations usually happen.

"We are fighting to stop this, to close this Dublin center because it could be the start of many others," he said.

The concert drew a curious crowd from the reception center, eager for entertainment and to share their stories.

"The camp is not that good, honestly," said Kareem Nasir, 28, who came to Germany via Turkey and Greece "to find peace" from war-torn Sudan. "They don’t have good bathrooms, toilets, privacy, there are a lot of people in one room," he said.

Many were concerned and confused about the new Dublin center, wary of a system with the potential to further restrict freedom of movement and reduce benefits.

"I have some friends, a few people I have spoken to who came from Poland, and it’s more difficult for them," said a young man from Cameroon who did not wish to give his name. "I don’t think it’s the best experience for any human being… being separate or apart from other people."

Read AlsoRefugees in Germany report more xenophobia

'We are living in constant anxiety'

People who directly experienced the Dublin center were reluctant to speak to the press. Only one man who had stayed in the center in March agreed to testify on condition of anonymity.

Speaking to InfoMigrants in Berlin, the man, who is from Sudan, spoke in Arabic and described a more restrictive setup compared to the rest of the camp, increased supervision and "living in anxiety".

Deported to Poland from the Eisenhüttenstadt Dublin center in April, he returned to Germany the same day and was eventually taken in by a local church parish as part of what is known as church asylum.

His testimony echoed the June open letter denouncing the new center. "We are suffering and are in constant fear and anxiety of deportation, because of frequent, unannounced police visits," it said.

Jansen dismissed the allegations as “probably made up” to raise media attention. He said all people staying at the reception center were treated equally, and that courts had thrown out legislation allowing reduced benefits in the Dublin center.

For ECRE’s Testi, the priority now is to understand where the Dublin centers are leading in Germany and how restrictive they could be allowed to become under the new EU Migration Pact, which is expected to take effect in 2026, and has more leeway for restricting reception conditions.

"Conditions in these centers always have to be kept under surveillance," she said.

Read AlsoGermany moves to implement EU asylum reform