What does Finland's tightening of migration and asylum policies mean for NGOs and migrant support organizations? InfoMigrants talked to non-profits Startup Refugees, which matches asylum seekers with companies, and Living Room, which provides afternoon activities for unaccompanied minors, as well as the International House Helsinki, which offers a wide range of information and public services for immigrants.

An "inclusive society, where refugees, asylum seekers and migrants have fast and equal access to a meaningful professional life".

The vision of Finnish non-profit Startup Refugees, enshrined in a poster hanging on a wall in its Helsinki office, stands in stark contrast to the course Finland has taken as a whole since the current government came to power in 2023.

Among other things, the rules for family reunification, financial aid for asylum seekers, rules for work-based residence permits and the entry of foreigners have become stricter. In addition, the right to asylum has effectively been suspended.

"Our customers are much more worried and more desperate," says Startup Refugees CEO Aicha Manai. Her team of 25 staff rely on a matchmaking tool with almost 10,000 profiles to match asylum seekers with companies, mentors and training.

"The government has also cut the rights of immigrants in terms of how much money they need to make in order to stay in Finland, how much money they need in order to bring their kids to Finland, and so on. We can physically feel the stress of our customers a lot more currently than we did three years ago."

This year alone, ten law changes have come into effect that make life considerably harder for asylum seekers, migrants and refugees in Finland. Since June, for instance, most work-based residence permit holders only have three months to find new employment, or face deportation.

When InfoMigrants first reported on the time limit last year, people told us that finding a new job in three months is unrealistic. "Research shows that even locals need more than six months to find a new job. So how do they expect an international to get one in three?," brand strategist and career advisor Lukumanu Iddrisu said.

Read AlsoSmall changes, big consequences: Stricter migration policies make job seeking harder in Finland

Uncertainty, fewer options and less money

Aside from taking a toll on her customers' well-being, Startup Refugees CEO Manai fears that the heightened uncertainty from the new rules and Finland's current trajectory overall will lead to a "considerable loss of talent."

Perhaps the biggest blow to the organization's work has been the termination of the so-called track change, which until a year ago allowed asylum seekers to apply for work-related residence. Before that, Startup Refugees helped hundreds of asylum seekers find work during the asylum process, improving their chances of being granted asylum.

"From an employer's perspective, hiring an asylum seeker is much less attractive now than it was before, when they also didn't know for sure if they're able to get their work-based residence permit," she told InfoMigrants. "But at least the option was there. Without the track change option, the threshold of hiring an asylum seeker has become much higher."

Another setback for Startup Refugees are the government's funding cuts affecting all NGOs, to varying degrees.

"We have been receiving about 100,000 euros annually from the Ministry of Education and Culture to support refugee youth's entrepreneurial skills, and this funding has now been completely cut," Manai said.

The Finnish Refugee Council was hit even harder: "Hundreds of thousands of euros in cuts" forced it to lay off six staff and furlough an additional ten, the organization announced in June.

And things could get worse soon: In December, the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, whose money makes up around 20 percent of Startup Refugees' budget, is expected to cut NGO funding even further.

Startup Refugees receives around 70 percent of its funding from Finnish public services, private foundations and the European Union, according to Manai, with the rest coming from donations and selling services like training and courses to municipalities, cities and companies.

'We don't want immigrants to be alone'

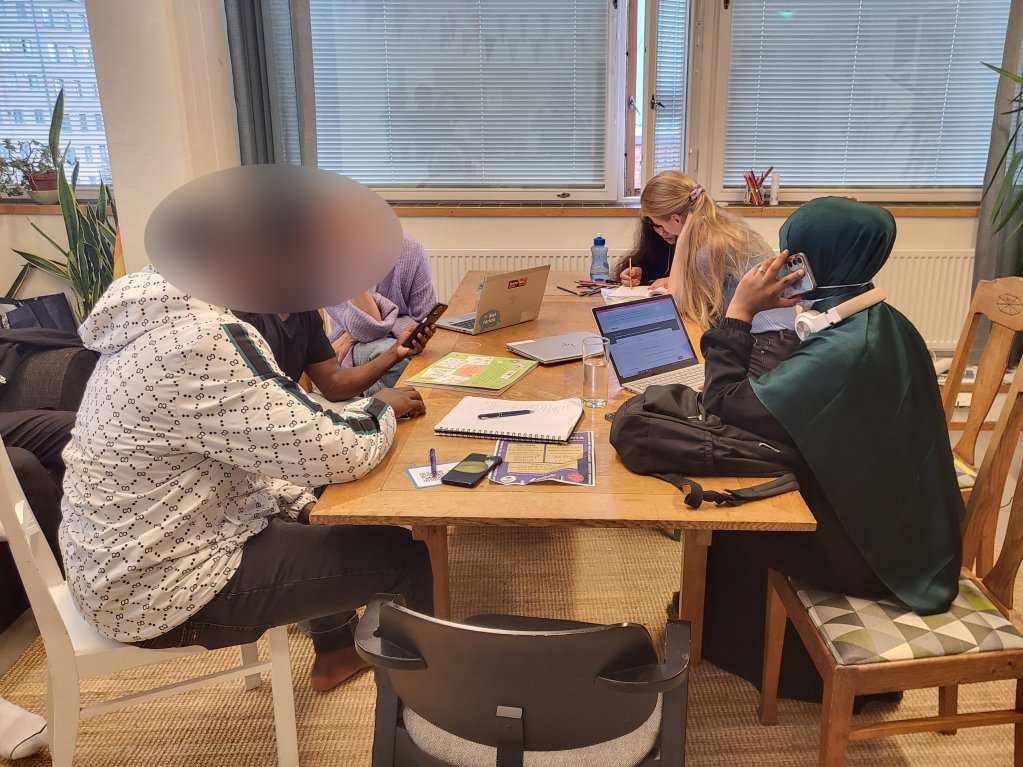

Down the hall from the Startup Refugees office in Helsinki's Hall of Culture, another NGO offers its support for migrants. It translates to Living Room, and the name says it all.

"When I first heard about this project, I thought I could help address what migrant youth are struggling with, including loneliness. So I was so thrilled to help create a space people can come to," says Joonatan Nsukami, who describes his role with Living Room as a "big family's dad".

Together with two other full-time and one part-time staff plus volunteers, Nsukami organizes a variety of activities like cinema visits and language learning for unaccompanied minors.

"When you've been through a lot as a kid, as an adult, you need a space to face it and get through it. Plus it's not easy to integrate into Finnish society -- it's hard to get a job, hard to get an apartment, hard to get friends," Nsukami told InfoMigrants. "We don't want immigrants to be alone."

The son of Congolese immigrants says the "very bad situation in the job market" -- Finland's unemployment rate currently stands at around ten percent, a 20-year high and the second-highest among EU countries behind Spain -- is especially bad for immigrants.

"We've seen youth whose family is in a difficult situation, with older family members unable to get jobs. In many cases, the kids will take on the parents' role," explains Nsukami, who came to Finland at the age of six.

Shabir has been a regular guest at the Living Room for more than three years. "When I'm free, I just come here," he told InfoMigrants. "I like the people, they help me with homework." He also enjoys spending time here with his friends, including other Afghans: "Speaking Farsi with them makes me feel good," he says.

According to Nsukami, Living Room has been able to buck the trend of having to scale down its operations due to less government support. Thanks to its foundation money, they'll be opening one additional Living Room in Helsinki as well as one each in three other Finnish cities over the course of the next months, Nsukami says. Other non-profits, in contrast, "are having a really tough time at the moment," he reports.

Read AlsoFinland: Parliament reduces accommodation capacities, cuts financial aid to asylum seekers

A short history of (im)migration to Finland

Similar to its Scandinavian neighbors, Finnish society has stayed relatively homogenous over the years, arguably to this day.

The first notable immigration movement other than from Russia occurred in the early 1990s, when the now EU member state received 1,500 refugees from Somalia over the span of a year. Their arrival prompted a racist backlash in society and in politics.

While the number of foreigners in the country gradually increased, especially through work- and family-based immigration, the so-called migration crisis in 2015/16 marked the first time a large number of people arrived in a short period of time.

Given that Finland was harder to reach than most other EU countries, very few migrants arrived initially. But then in late summer and early fall of 2015, two things happened: Migrants realized that it would take a long time in places like Germany to process their asylum applications; and the Finnish Prime Minister at the time offered his country house to refugees, which made international headlines. These things led to a rapid rise in the number of arrivals that was followed by a similarly rapid decline.

Between August 2015 and February 2016, about 30,000 mostly Iraqi and Afghan migrants and refugees had arrived via Sweden. Finland ranked fifth among European countries in asylum applications per capita in 2015, behind Norway, Austria, Sweden and Hungary, but ahead of Germany.

Although people's initial reaction was mostly positive, it didn't take long for the public sentiment and politics to turn from welcoming to hostile, albeit inviting attitudes also persisted.

"Already in December of 2015, the government launched a program with the aim of preventing asylum seekers from coming to Finland," Erna Bodström, a researcher at the Migration Institute of Finland, told InfoMigrants. "It was actually talking about 'uncontrolled migration'."

Starting in 2016 and spearheaded by the right-wing populist, anti-immigration Finns party, which currently polls at around 13 percent, the government then introduced law changes that included abolishing one category of international protection and making family reunification harder.

Six years later, the next arrival of a large group of refugees occurred following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Unlike 2015, Finland's reaction was overwhelmingly -- and sustainably -- welcoming.

Altogether, some 80,000 Ukrainians have arrived in Finland over the past three and half years, or roughly 1.5 percent of Finland's population of 5.6 million.

In the 2023 election, finally, the Finns party came to power for the second time and succeeded in imposing on their coalition partners their anti-immigrant agenda, which directly or indirectly affects the around one in ten people in Finland who migrated there, or were born to parents who did.

Read AlsoPortugal introduces law to limit migration

Cuts to integration funding

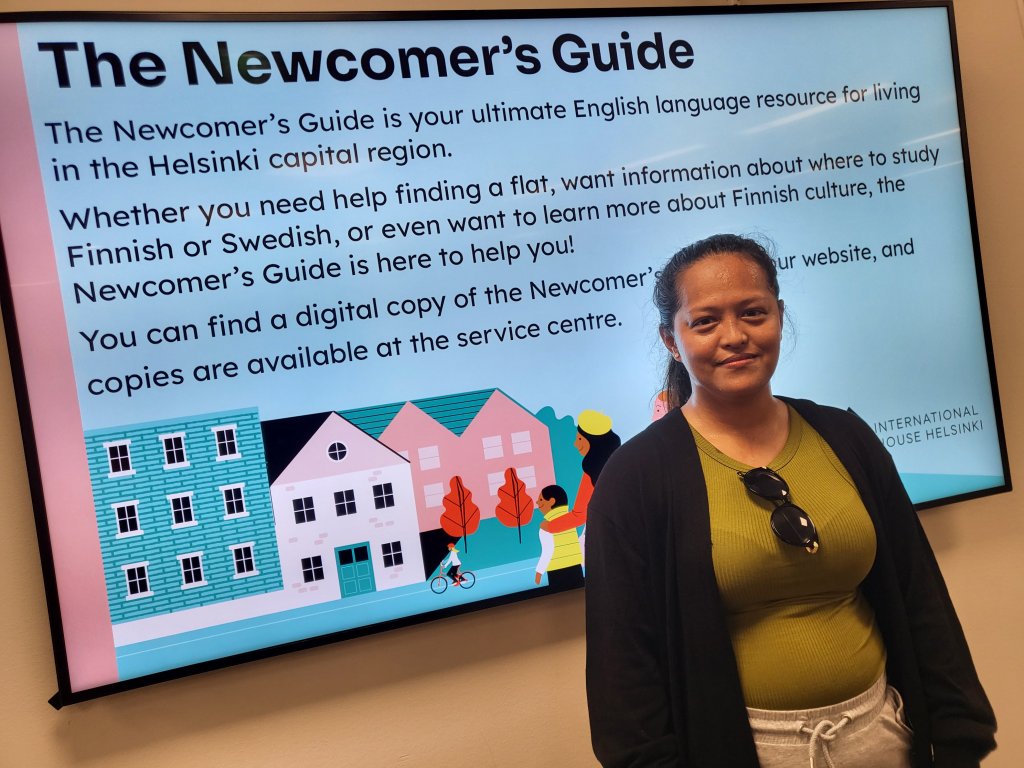

After a 22-minute walk from the Startup Refugees office past Helsinki's imposing Kallio Church, one reaches a red brick edifice that houses the International House Helsinki (IHH), which many consider an important place for newcomers in Finland.

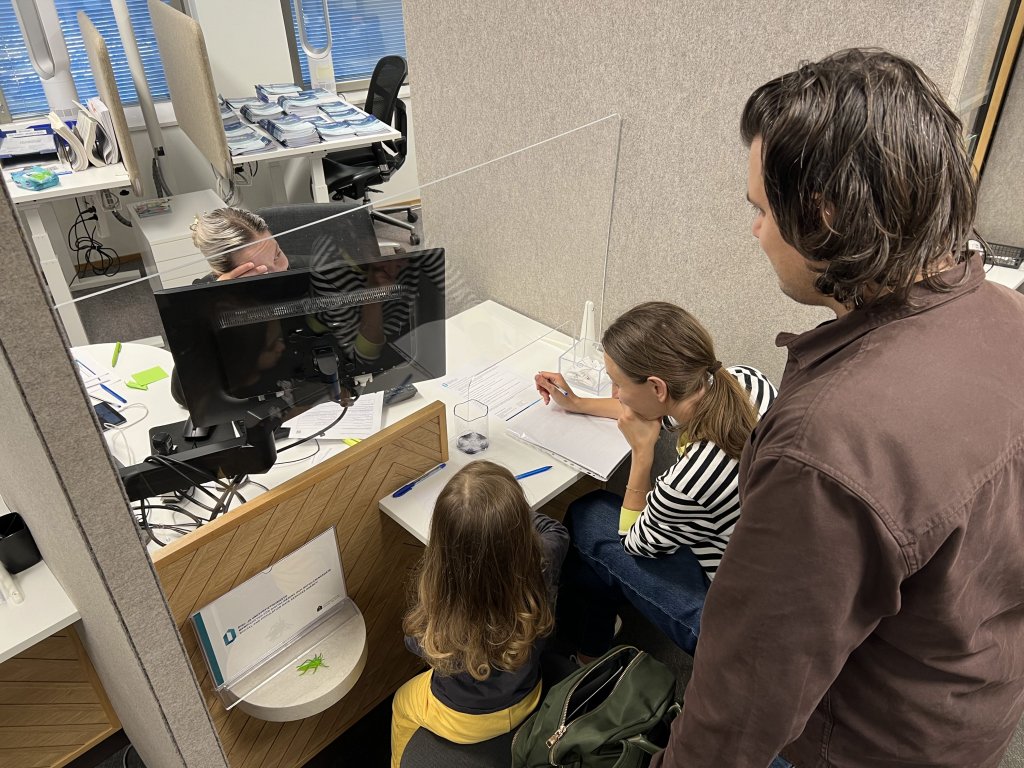

Opened in 2017, the space entails five public authority services, including the Finnish Tax Administration and Migri, the Finnish Immigration Service. Among other things, newcomers can register their residence, access employment services or receive information on child care and education.

According to City of Helsinki’s Director of Migration Affairs Glenn Gassen, some 40 percent of all immigrants to Finland go through IHH. The figure increases to 60 percent when only counting people with specialists' residence permits.

Gassen says the aim is a "two-week service promise", meaning it shouldn't take longer to get all important tasks taken care of, and a "one-stop shop principle", which means that once a piece of data has been collected, it should be digitalized so that all other agencies can access it and don't have to request it again.

While digitizing government services for migrants is a priority for Gassen and his team, what really worries him are the funding cuts to Finland's reception and integration system.

Federal money for immigrant integration was cut by 58 million for this year and is expected to be cut by a further 52 million next year. And although recently announced additional cuts to integration services were less drastic than initially announced -- one fifth (30 million euros) starting in 2027 -- Gassen thinks the "overall picture" for regular and irregular migrants is "quite severe", not the least because municipalities have been put in charge of integrating immigrants.

Municipalities having to take on this responsibility from the state with far less money at their disposal to cover each level in the reception system is a "very difficult combination," Gassen says.

He fears that the hollowing out of integration services will hurt migrants' job prospects and, in turn, further weaken Finland's ailing economy.

"At the end of the day, what matters most is that we get people employed, integrated and thereby also strengthen the Finnish economy," Gassen told InfoMigrants. "But with these changes, we will not be able to offer these integration services to everyone in the long run."

Read AlsoRussia alleged to be smuggling migrants to Europe in 'hybrid attack'

'We need more taxpayers'

To international observers, the most visible measure taken by the Finnish government has been the border closures with Russia.

Migrants from Syria, Somalia, Iraq and other countries started arriving at the Russia-Finland border in August 2023. Four months later, Finland closed its land borders indefinitely, citing national security concerns. The Finnish government claimed that Russia was instrumentalizing them.

In addition to the border closures, Finland's Parliament last July passed a bill dubbed the instrumentalization act, which makes it easier for border guards to turn back migrants at the border with Russia without them being able to apply for asylum. The controversial law, which was renewed again in June, is intended to further improve border security and stop irregular migration from Russia.

The closures have had far-reaching consequences on the border region.

"360 million [euros per year] turnover was brought by Russian tourists to the South Karelia region yearly, and that has disappeared," Lappeenranta city official Ding Ma told InfoMigrants.

Ma, whose parents emigrated from China to Finland in the 1990s, is not only concerned about the border closures. He believes the tightening of national asylum and migration policies have been hurting Finland's image.

"We see that the birthrate is decreasing all the time, and the population is aging, so we need more taxpayers, more citizens here in Lappeenranta. Immigrants play an important role in this sense. My biggest concern is that the overall atmosphere makes immigrants less welcome."

Earlier this year, Finland completed the first part of a fence on its 1,300-kilometer border with Russia to prevent migrant crossings. Construction of the border barrier, which began last year, will eventually cover 200 kilometers and is expected to be completed next year.

Gwenaëlle Bauvois, who studies the radical right, extremism and anti-immigration movements at the University of Helsinki, warns that framing border security through the lens of national security often leads to policies and practices that will "target specific ethnic, racial and religious groups."

"This can really create a climate of fear and suspicion around migrants and individuals from certain countries," she told InfoMigrants. "And it reinforces negative stereotypes and fuels xenophobic attitudes. It's exactly what we witnessed in 2015/16 during the large number of migrant arrivals, which was mostly framed in Finland through security."

No end in sight

In addition to the hollowing out of integration services, funding cuts for NGOs and tougher rules for migrants in the context of the labor market, the government has also made it more difficult this year to be granted a residence permit and to continue to stay through permanent residence or citizenship, among other things.

Aforementioned migration researcher Bodström thinks the restrictions have made it more challenging for all migrants to build a stable life in Finland.

"The law changes affect asylum seekers and refugees in particular, but also work-, study- and family-based migrants," Bodström told InfoMigrants. "This all increases the insecurity in the lives of even established migrants in Finland," she concludes.

Provided the four-party government coalition remains intact, Bodström expects its restrictive course to continue -- at least until the next parliamentary elections, which are slated for April 2027.