The Terra Nova think tank recently published a report on how the Spanish government encourages labor migration while multiplying security deals with transit and departure countries to limit arrivals at its borders. The co-author of the report, Tania Racho, discussed the phenomenon in an interview with InfoMigrants.

Spain, for years a country of emigration, has since become one of the main host countries for immigration in the European Union (EU). An August 2025 report published by the Terra Nova think-tank studied the "Spanish exception," since the country stands out in the EU for having adopted a migratory policy known for legalizing undocumented migrants. In 2025, nearly 19 percent of the Spanish population were immigrants.

A co-author of the report, Tania Racho, a researcher on European law and specialist in asylum rights, discussed the strengths of this open-door policy, its persistent failures, and the security-focused approach imposed by the EU, which has led to the externalization of borders.

InfoMigrants: What have been the results of the Spanish government’s open stance on immigration?

Tania Racho: The results are already visible in the GDP: the figure rises every six months, which is not the case for other European countries. Immigration is undeniably one of the factors of this increase, though it’s not the only one.

Spain's gross domestic product reached 3.2 percent in 2024, one of the highest growth rates in the EU. In early 2025, Spain was the only European country that experienced GDP growth.

The Spanish government's objective is clear: it seeks economic immigration, based on inclusion through employment, meant to boost the workforce. This is in spite of all the potential negative consequences, like a mismatch between the foreign worker’s skills and the jobs they hold. Many foreigners in Spain work in the tourism or agricultural sectors, with seasonal and flexible contracts.

In some sectors, the contribution of foreign workers to the country's economy represents nearly 50 percent of the workforce.

Read AlsoSpain: Immigrant labor bridging job market gaps

From a demographic perspective, Spain had a declining birth rate, a trend that would have continued in the absence of immigration. The influx of immigrants therefore had a positive impact on Spain's demographics, providing additional labor and a younger population.

The government wants to legalize 900,000 foreign workers in Spain over three years, at a rate of 300,000 undocumented immigrants to be granted legal status annually starting in 2025. This is quite interesting since it’s unknown whether there are even that many undocumented immigrants in the country.

IM: What is the Spanish population’s perception of migrants, and what explains it?

The Spanish government’s way of talking about foreigners and the vocabulary it uses are totally different from what we usually hear in France and in Europe. When the rhetoric of political leaders is open and supportive of immigration, it has an impact on public opinion. The Minister of Territorial Policy and Democratic Memory, Ángel Víctor Torres, for example spoke of the importance of providing dignified treatment to unaccompanied minors in Spain, particularly in the Canary Islands. He called it a "duty toward these children". This is very different from the way the issue of unaccompanied minors is treated in France.

Read AlsoSpain: Prime Minister promotes positive migration messages in speech

The Spanish public opinion is conscious of the crucial need for this labor force made up of foreign workers. It is worth remembering that the largest-ever regularization program [600,000 undocumented migrants were regularized in 2005, editor’s note] was the result of a grassroots initiative stemming from a citizen movement. Contrary to popular belief, successive waves of regularization did not lead to massive influxes of migrants, nor did they create a "magnet effect". This remains true 20 years later.

Trade unions and associations of employers are also very involved in these initiatives. Housing issues remain in large cities of course, and integration remains more complex. The system of integration is more effective outside of big urban centers; some companies even directly approach migrant reception centers to hire foreign workers.

Finally, while the media sometimes plays an ambivalent role by perpetuating stereotypes about migrants, it has still managed to present diverse perspectives on the issue of migration. This contributes to fostering a more positive outlook on the issue.

IM: Your report highlights some significant shortcomings (unequal access to rights, complex procedures, the emphasis on work visas, and tensions in the Canary Islands and the enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla). How does this affect immigrants, and could it contribute to polarizing Spanish society?

TR: Like the other countries in the Schengen Area, Spain aligned itself with the European policy of visas, basing its management of asylum requests on the EU's. While immigration through work is encouraged by the government and the state is free to define its economic immigration, the approach concerning asylum is a lot less open in Spain.

The country’s protection rate was only 19.8 percent in 2024 (in contrast with 39 percent in France). Asylum seekers are frequently redirected toward temporary humanitarian visas or a system of regularization through labor. There is clearly a European game to encourage Spain to act this way.

The Spanish Ombudsman revealed in 2022 that there were not enough facilities to accommodate asylum seekers in Spain. Many people ended up homeless as a result. These European asylum procedures are strongly criticized by NGOs and human rights organizations, which condemn their slowness and complexity.

There are specific strategic and political stakes in the Ceuta and Melilla enclaves [which face a significant increase in migrant arrivals, editor’s note]. The proper investments haven’t been made to properly treat applications from migrants. Migrant transfers occur between the two enclaves and the Spanish mainland, but they happen in an opaque manner.

In 2015, Spain adopted a legal measure of immediate pushbacks from the borders in case of illegal entry into the enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla.

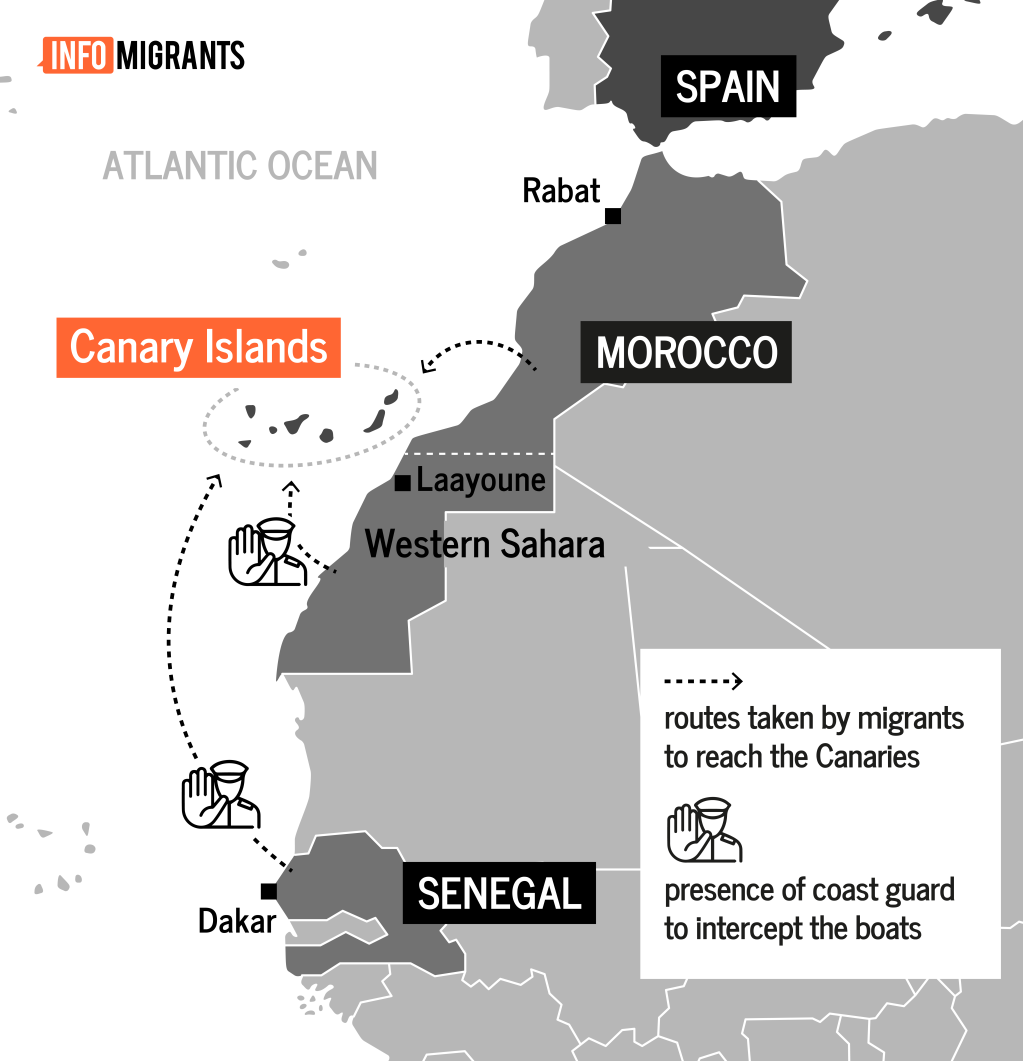

The question is also complex for the Canary Islands, whose reception system has been strained by the increasing number of migrant arrivals. Yet it’s important to put these arrivals into perspective: there were nearly 47,000 arrivals in the Canaries in 2024, and they were later transferred to different Spanish communes.

The anti-migrant riots which broke out in July near Murcia, in southern Spain, show how tense the situation has become lately in several European countries. The extreme right party is on the rise (the party Vox is now the third biggest political party in the country, editor’s note). These recurring themes are linked to regional problems, like the Catalonia issue. For the populist party, hating migrants has a political advantage. The Spanish are conscious of this.

IM: How does Spain reconcile its open migration policy within its borders, driven by economic interests, with the strict border control requirements imposed by the EU, particularly through its security cooperation agreements with transit and origin countries?

TR: Spain has double standards. The government supported the European Pact on Migration and Asylum, which foresees treating a portion of asylum requests outside of the EU. Spain has been avant-garde on the issue of externalizing borders, by adopting maneuvers to fight against departures and push the migrants to the EU borders. It also became closer to several countries through agreements to cooperate. This is the case with Morocco, an economic partner, but also with Mauritania and Senegal on the security aspects of migration.

European countries have the desire to completely control the arrivals on their territory because the EU wants to control the Schengen zone and ensure free movement within the zone. For several years, the countries reintroduced controls on the internal borders, justifying this by the importance of controlling immigration. The pressure is also felt on external borders. There is also tension, aggravated by terrorism and the massive arrivals of Syrians over the last ten years. The European countries are hiding behind these security controls to try to control every person, by registering their information in a database. Spain plays this game like all the other member states in the EU.

Read AlsoHRW accuses Mauritania of serious violations of migrants' rights