For nearly 30 years, the Ikambere association in Saint-Denis, a suburb just north of Paris, has welcomed HIV-positive women, most of them migrants and living in extreme poverty. This center, which offers group workshops as well as social and therapeutic support, has become a refuge for many of them. There, they are gradually trying to reconnect with their bodies and hearts.

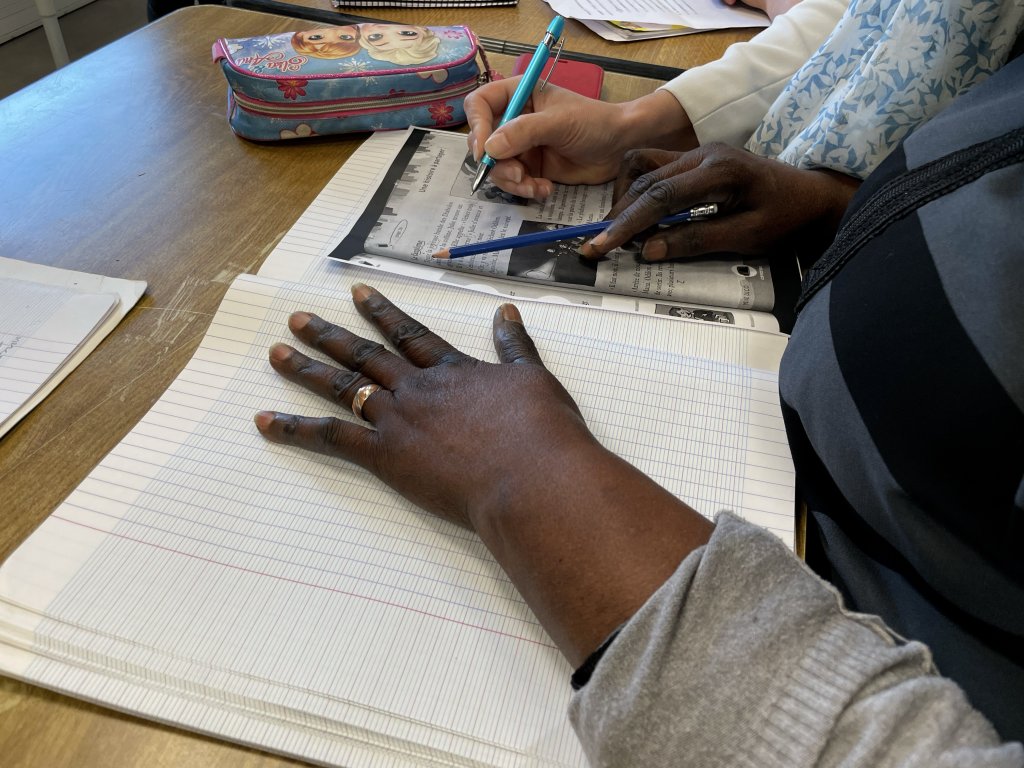

"It's like our home here." In the activity room, converted into a classroom for two hours, Odile* is busy copying the day's date into her notebook. This 80-year-old Cameroonian woman -- one of the oldest members of the school -- got up at the crack of dawn to be on time for the literacy class. A total of four women came that morning. All had more than an hour's commute to reach the Ikambere** association's day center, nestled on the ground floor of a building in Saint-Denis (north of Paris).

But despite the time spent commuting, Odile and the others make a point of attending every session. "If I miss a class, like a doctor's appointment, it really bothers me," the octogenarian says, concentrating on her task. "Here, I feel good, I have friends, people to talk to. People who understand me," she adds with a smile.

Because in Ikambere, the women welcomed all have one thing in common: they are all living with HIV.

When she was diagnosed with the disease in 2015, Odile felt her world collapse. "I was as if I were dead," she says. She left for France to seek treatment because "HIV treatments aren't good in Cameroon." She obtained a residence permit and then a place in social housing in the Île-de-France region. Even today, only her children know about her health status.

"I wasn't ashamed of the disease, but of myself. When I arrived in France, it was very hard. I was alone, exhausted, I didn't know if I would survive. Then, last year, my doctor told me about Ikambere. It changed my life. My blood pressure went down, my physical condition improved... Today, I have no money, I have almost nothing, but here, my heart has been restored," she sighs.

'Resurrecting women who are dead in body and spirit'

Founded in 1997, right during the "AIDS years," the Ikambere shelter supports around 500 women living with HIV each year, most of them migrants and in very precarious situations.

"These are often women who have been crushed by life. They arrive here completely disconnected from themselves because they have multiple vulnerabilities: they are infected with HIV, they are migrants, they have experienced stigmatization, are isolated, and rejected because of the virus," Rose Nguekeng, a sexual health counselor at the association, explained. "In the face of this, Ikambere is a place of life that attempts to resuscitate these women who have died in body and mind."

When they first arrive at the facility -- with or without an appointment -- the women are systematically welcomed and interviewed by a social worker. In addition to helping them with their administrative procedures and providing social support, the center offers daily group workshops (sports, dance, nutrition, literacy, socio-aesthetic therapy, etc.) to help them overcome their isolation.

"The beneficiaries are often marked by very difficult experiences, so we try to be a place of joy and calm for them. A place where they can talk freely about the disease, exercise for free, eat well, and connect with other women," Fatem-Zahra Bennis, the association's deputy director, said. Above all, the teams teach them how to live with HIV and deconstruct certain preconceived notions about the virus through information sessions and discussions with doctors.

Escaping the weight of stigma

At the other end of the table, Bineta* practices reading aloud and deciphering the words on the sheet of paper in front of her. This discreet 50-year-old from Guinea-Bissau, like many others, carries internalized stigma surrounding her illness. "Where I come from, HIV is frowned upon. People think that HIV-positive people are 'tainted.' When I learned I was infected in 2005, my cousin, who I was living with, threw me out onto the street. Apart from her, I only told my mother, I was so ashamed. For me, life stopped. I attempted suicide several times," she says, her gaze drifting.

Her story is far from a unique one. "These migrant women, particularly those from sub-Saharan Africa, grew up in an environment where anyone infected with HIV is labeled as a person of bad reputation, a prostitute. So when a woman realizes she's HIV-positive, she thinks that if she talks about it, she'll be rejected. So she lives in silence. But it's a silence that kills," Rose Nguekeng explained.

Bineta is a regular at the welcoming center: she's been coming to the center for almost 15 years "every day, from opening to closing," she proudly says. Here, the woman who thought she was doomed learned that it is possible to live thanks to HIV treatment. Yet, even years later, the road to accepting the disease is still sometimes long. "There are days when I break down. But coming here gives me a little relief," she says.

Like Bineta, many have gone into exile to escape the burden of marginalization and the judgment of others. This is also the case for Imane*, a 33-year-old Algerian woman who was diagnosed with HIV in 2013 and arrived in France three years ago. With her impeccable ponytail pinned to her head, the young woman is doing her French exercises while sharing her story.

"When I found out I had HIV, I tried to commit suicide because, for me, it was over. My family didn't accept the disease; they hid it from everyone. They told me I was 'dirty,' that I'd done 'stupid things.' I couldn't take it anymore, so I decided to leave," she says.

Imane then boarded a dinghy alone from Algeria and reached the Spanish Balearic Islands before reaching France. She has cut off all contact with her family.

The young undocumented Algerian woman has been housed through the 115 emergency helpline and has been going to Ikambere every day for over a year. "I feel more and more comfortable here. Before, I was ashamed. I felt guilty, dirty, because of HIV. I didn't trust anyone. But here, I have hope again: even though we're not the same age, these women have the same stories as me," she whispers.

Intergenerational solidarity

At the end of the French class, Imane, Bineta, and Odile -- soon joined by new participants -- swap their notebooks and pencils for stretching bands and fitness balls. It's noon: the physical exercises can begin.

On one side of the room, the older women climb onto the few workout machines available. On the other, Imane and two other younger women do core exercises. For an hour, the Algerian woman's smile never leaves her face. The fitness coach, Luc, puts on African music on the sound system. "They love it and it motivates them," he smiles.

While pedaling one of the bikes, Bineta looks kindly at the younger women on their exercise mats. "It makes me feel good to be surrounded by them, to see such strong young women." In the center, women of 35 different nationalities -- aged 25 to 80 -- work side by side. The solidarity that has grown among them over the years is one of the association's main pillars.

"Talking with others, seeing everything they continue to do despite HIV, I realized that my life isn't over," Imane, folding up her mat, tells us. Here, she learned that she can still fulfill one of her dreams, which she imagined she would have to give up: to one day become a mother. "I thought that if I had a baby, it would inevitably be doomed to live with HIV too. But I discovered that with the right treatment, it's possible to have a healthy child," she says, moved.

At the end of the workout, the twenty or so women head to the kitchen, which opens onto the colorful dining room, where, every day, a full meal awaits them. They take turns helping themselves, amidst the surrounding laughter and conversations. Imane is already eager to participate in the day's upcoming activities. To prove to herself, tirelessly, that she is still alive and much more than the disease.

*All names have been changed to protect the women's anonymity.

** Ikambere's "Welcoming House" is open from 9 am to 6 pm, Monday to Friday.

There's also the Igikali "soothing house" in Ivry-sur-Seine, for women living with diabetes, obesity, or high blood pressure.

➡️ More information about Ikambere here: https://ikambere.com/