The Tunisian government is prohibiting undocumented migrants from receiving foreign currency and from working. This new crackdown is an attempt to dry up the income of smugglers, particularly in the Sfax region. It has plunged already destitute Sub-Saharan Africans into extreme poverty.

Thomas* is living in extreme hardship in Tunis. The Nigerian, who has been living undocumented in Tunisia for several years, sinks deeper into poverty every day. "I was getting by before, but now I'm begging in the streets," he said. Thomas survived being expelled into the Tunisian-Libyan desert near Ras Jedir in the summer of 2023. Like most sub-Saharan Africans without residence permits in Tunisia, he cannot count on outside help. He can neither send nor receive money through currency transfer agencies, whether they are banks or post offices. "You are asked to leave if you try to enter an agency being Black," he says.

Currency transfers in Tunisia are subject to strict regulations, said a professor specialized in migration, contacted by InfoMigrants. Tunisians, like foreigners who have papers, can receive currency from abroad. Yet they are prohibited from exporting Tunisian currency. "For undocumented foreigners, it's worse. Tunisian authorities have drastically restricted their access to banks and post offices to collect international remittances and transfers from abroad."

Read Also'You become a target if you are Black', says Ivorian jailed in Tunisia for 'illegal residence'

'Enormous and shocking amounts', according to Kaïs Saïed

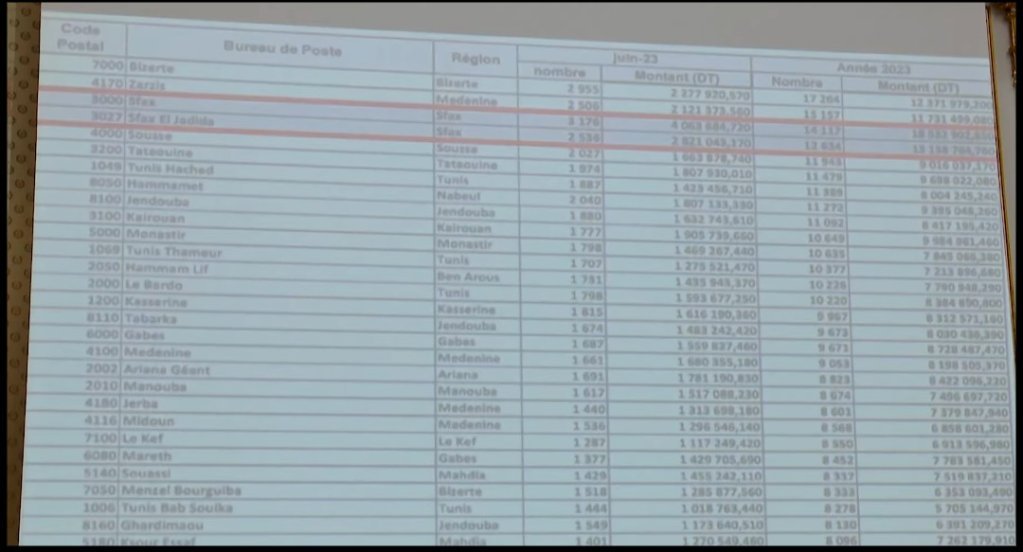

The restrictions began in the summer of 2023, following a presidential meeting held on July 14 that was broadcast on Facebook. In a long speech hostile to irregular immigration, President Kaïs Saïed condemned money transfers from African countries to Sfax, a port city southeast of Tunis. "Huge sums" were allowing a parallel economy managed by smugglers to flourish, according to the president. "[These transfers] prove that human traffickers are attacking the homeland," said Saiëd. Sfax is one of Tunisia’s main departure points for Mediterranean crossings to Lampedusa – a gateway to the European Union (EU). Smugglers are numerous there, and so is the circulation of foreign currency used to pay for sea travel.

Some 23 million dinars – approximately 6 million euros – were transferred to sub-Saharan Africans in the city of Sfax alone in the first semester of 2023, according to figures displayed on a large screen during the meeting. "We have the names of the people who received these sums," said the Tunisian president.

"The Tunisian authorities are reinforcing their crackdown [on migrants]," said Romdhane Ben Amor, spokesperson for the Tunisian Forum for Economic and Social Rights (FTDES), a non-governmental organization (NGO) for migrant rights. "Life has become economically impossible for migrants since this political shift in July 2023 [...] They were able to get by before with MoneyGram, Western Union... [money transfer agencies, editor's note] It wasn't always easy, but they were able to collect money by showing their passport, regardless of their administrative situation. This is no longer the case. You need proper papers to withdraw money," said Ben Amor.

"The authorities want to make the situation unbearable to force migrants to leave the country," added the spokesperson. There are between 20,000 and 25,000 sub-Saharan exiles in Tunisia, according to NGOs.

‘A total break with a part of the population’

The Tunisian presidency has issued other warnings in addition to the banking prohibition. Tunisians are now prohibited from employing undocumented sub-Saharan Africans or renting apartments to them. Migrants are strictly forbidden from setting up informal camps in the olive groves of the Sfax region. "It’s important not to underestimate the importance of public opinion which is pushing the government to implement a harsh policy towards sub-Saharan Africans," said Ben Amor.

"The government wants to establish a form of apartheid, a total break with part of the population: migrants can no longer find housing, they can no longer work, they can no longer receive money from their families, they can no longer be approached by NGOs [also victims of Tunisian policy since they are accused of being ‘foreign agents’ and encouraging irregular immigration, editor's note],” said the spokesperson of the FTDES. "Migrants are stuck."

Thomas, like many migrants, has gone from a situation of economic precarity to extreme poverty since the summer of 2023. "I knew a Tunisian who was able to help me," he said. "He received the money for me via his bank account and then gave it to me, while taking a commission. I could eat and pay my rent." His contact became fearful in the past few months. "He simply told me he could no longer help me, that he was afraid of being discovered by the police."

Read Also'Libyans, armed and hooded, picked us up in the desert' – testimony of a Guinean in Tunisia

Thomas and the other migrants are economically cornered, relying exclusively on increasingly rare and increasingly "greedy” intermediaries. Some not only charge "excessive" commissions, but others even disappear with all the money. It's also impossible to count on help from the Tunisians. "The authorities have already arrested civilians who had received money orders for the Africans, especially in the Sfax region. Even Tunisian women have been arrested because of these small-scale money trafficking schemes," said Ben Amor.

‘To get money, we make do’

In the olive groves, migrants have learned to live without resources. "It doesn't change anything for me; I've never been able to receive money," says Marie, contacted by InfoMigrants. She lives in one of the camps in the Sfax region, “far from the city, far from banks. To get money, we make do," she said without elaborating. Some people barter, she said, while others use Orange Money, a system that doesn't require going to the bank or the post office.

Others, like Louis, live off the solidarity of their neighbors in the camp. "I haven't worked for three months. We used to be able to get hired in Sfax," said the Ivorian, father of two children, aged eight months and eight years. They live in the "km 27" camp, between Sfax and Jebenania. "We would walk around, meet Tunisians and they would give us day jobs. I used to work in the fields here, earning 25 dinars a day [about 7 euros, editor's note]. When I was in Tunis, I was a mason on construction sites. That's over now, I stay in the camp all day, and the Tunisians don't dare hire us. It's very hard. Everything has changed... Luckily, my friends are helping me; their generosity has saved me."

‘I’m stuck here, I don’t know what to do’

Without a salary, Louis can no longer pay the smugglers to attempt a Mediterranean crossing. He tried to reach the Italian island of Lampedusa twice before the National Guard stopped his boat. That was before the arrival of his youngest child. He and his family are facing a dead-end. "I can't return to Ivory Coast. I'm receiving death threats there and I can't pay the smugglers. I'm stuck here, I don't know what to do."

A record number of migrants returned home in 2024 with assistance from the International Organization for Migration (IOM): 7,250 people compared to 2,250 in 2023. These "voluntary" repatriations were encouraged by Kaïs Saïed. "All the organizations" should support "Tunisian efforts to facilitate the 'voluntary return' of irregular migrants," said the president at the end of March. Saiëd deplored that "only 1,544 migrants" had been repatriated during the first three months of the year.

Yet the trend seems to be reversing. Over 1,000 sub-Saharan Africans "voluntarily" returned to their country of origin in April 2025 alone, according to the latest figures from the authorities. This is a failure, according to NGOs. The Africans had no choice but to flee Tunisia after becoming the scapegoats of a presidential policy that had become virulently hostile toward them.

In addition to economic sanctions, migrants are also targeted by arbitrary arrests, convictions for "illegal residence," roundups, and abandonment in the desert. "I hardly leave my apartment anymore," said Thomas, stuck in the Tunisian capital. "I'm afraid of someone reporting me, I'm afraid of walking in the street, I'm afraid of dying."

*All first names of undocumented migrants have been changed