Aid and community centers like Halte Humanitaire Diderot in the French capital offer unaccompanied minors a place to shower, eat a hot meal, and even attend rap classes. By recreating the routines of everyday life, they provide not just basic services but also a sense of shelter and belonging.

Every day, anywhere between 60 to 100 young men make their way to the Halte Humanitaire Diderot drop-in center in the first arrondissement in Paris. Here, they can take a shower, eat a hot meal, wash their clothes, or charge their phones so they can keep in touch with family back home.

For these young men who are unaccompanied minors living in makeshift encampments scattered across Paris, life routines are not guaranteed. At the center -- even for a few hours -- these young men can have a semblance of stability.

On the Saturday morning that InfoMigrants went to visit Halte Humanitaire Diderot, most of the young men were gathered in the lounge area. Some were scrolling through phones, likely going through social media or checking in with family members thousands of miles away. A small group was huddled around a card game. One or two young men hovered by the small bookshelf that serves as the center’s library.

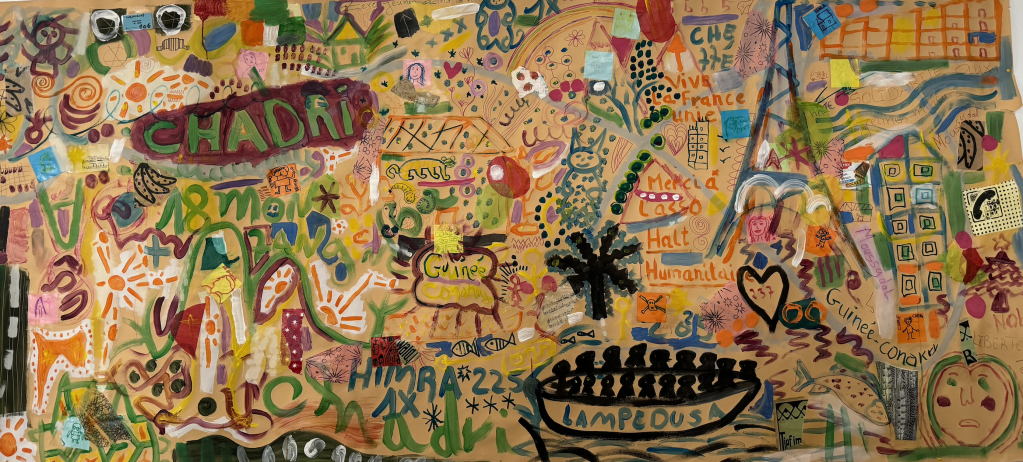

At the far end of the lounge, a mural drawn by some of the minors who have passed through the center stretches across the entire wall. Scenes from journeys that are long and perilous are relived through sketches and scribbles. An overcrowded boat labelled Lampedusa. Gratitude scribbled as Merci a l'asso Halte Humanitaire.

A calendar tacked on the wall near the entrance listed the center activities for the week -- French classes, sports events (this week it was boxing), and rap workshops. More than a schedule, it is a promise of normalcy. A break from the bureaucratic web of the asylum system and an invitation to belong.

"All of the young men who come here are minors, most of them from Guinea," Usman Ishaq, a shelter volunteer told InfoMigrants, explaining the easy flow of French conversations that filled the room.

Rooms line the back of the center, offering services such as social welfare support, legal advice, and medical care. According to Ishaq, medical services are most often sought by the young men -- a marker of the toll of living rough on the streets.

A system under strain

Thousands of unaccompanied children come to France each year, most arriving from West African countries like Guinea and Ivory Coast.

Upon their arrival, the juvenile migrants undergo an age assessment that determines whether they will receive child protection services such as accommodation, health care, legal assistance, and education, administered by the Social Assistance for Children (ASE).

On paper, the Ministry of Justice mandates that age assessments involve observation, identity verification, and interviews. However, numerous reports show that age assessments are often arbitrary, rushed, and inconsistently applied, burdening juvenile migrants with having to "prove" that they are minors.

A 2022 Ombudsman report (Défenseure des droits) underscored how young people declaring themselves minors are subjected to an evaluation process that involves multiple reassessments that have little consideration for their rights and background.

As a result, "some young people are wrongly declared adults and find themselves excluded from child protection systems, leaving them wandering and precarious, even during an appeal of this decision," the MPs reported.

A 2024 Human Rights Watch report focusing on Marseille revealed that about 50 percent of juvenile asylum applicants are initially denied recognition as children, which carries a string of consequences.

A negative age assessment -- or one that places an unaccompanied asylum seeker as an adult -- results in eviction from emergency shelters, forcing them on the streets where they are exposed to violence, exploitation, and trafficking.

A negative age assessment can be appealed. However, waiting for a resolution can drag on, leaving jeunes en recours -- young people appealing negative age assessments -- in a legal limbo where they are excluded from child protection services, such as shelter and basic services.

Read AlsoGuardian investigation: Drug cartels exploit migrant children for Europe's booming cocaine trade

'Low-cost care' and food insecurity

In 2023, unaccompanied minors lodged 43,000 applications for international protection in EU+ countries -- the highest number since 2016.

In France, a recent parliamentary report sharply criticized the treatment of unaccompanied minors, describing it as low–cost care that is "marked by rushed, often disrespectful assessments."

In response to the dire situation juvenile migrants face, Halte Humanitaire Diderot, along with partner associations, including Action Against Hunger, conducted a survey in 2023 across four Paris locations and interviewed 128 minors between 15 and 16 years old.

Most of the respondents were from Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire and had been in Paris for around three months. Nearly all of the 128 respondents (95 percent boys, 5 percent girls) were awaiting recognition as minors, however, only 3 percent were housed in shelters. About 91 percent reported sleeping on the street or in makeshift camps.

"I'm not doing well. I've been in France for six months, and I've been sleeping outside. I need help." -- 16-year-old boy

More than half of those surveyed, or about 53 percent, were found to be in a situation of "severe hunger," where they had not eaten for 24 hours and had gone to bed on an empty stomach. It is a level of hunger that was cited as more commonly seen in acute humanitarian crises, not in Paris, one of the richest cities in the world.

Another 16-year-old boy described his daily situation, "If I'm hungry, I can’t sleep. I walk around, I drink water, but I can’t fall asleep on an empty stomach, so I’m tired."

Access to hygiene and healthcare was equally dire. The estimated 89 percent who managed to wash regularly were able to do so at day shelters or public faucets. More than 60 percent reported ongoing health issues, but only 7 percent had regular access to medical care.

The respondents cited the hierarchy of their most urgent needs: education (75 percent), followed by accommodation (69 percent) and formal recognition of minority status (54 percent).

Read AlsoFrance: Parliamentary report slams 'low-cost care' for unaccompanied foreign minors

Living in survivor mode

The "zero fixation" policy employed by law enforcement in big cities like Paris makes matters worse. To prevent informal camps from spreading in public spaces, police disperse them -- without offering an alternative, and often reportedly resorting to confiscating tents, sleeping bags, and personal belongings. Verbal and physical abuse were also reported.

A 13-year-old cited in the survey said of their encounters with law enforcement, "Starting at 5 am, they come to drive everyone away. Even just sitting in front of the town hall, they don’t leave us alone."

Authorities claim that this is to prevent the emergence of large camps such as those seen in Calais or northern Paris. But for migrants, it results in constant displacement, instability, and deeper precarity, making it even harder for NGOs to provide aid and for individuals to access basic services.

Encounters with law enforcement, the resulting displacement, and the overall precariousness of their situation push many juvenile migrants into living with the deep psychological impact of being in constant survival mode.

Read AlsoParis: Migrants removed from City Hall camp by police

Reactional distress

According to the joint study by Halt Humanitaire Diderot and their partner associations, many young migrants show signs of "reactional distress" -- manifesting as anxiety, depression, nightmares, and withdrawal. Nearly 90 percent of the respondents had never seen a psychologist or psychiatrist, though many said they would like to. Aid and community organizations like Halte Humanitaire work to fill in the gap.

Anna Knutzen, United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) Chief of Child Protection for Europe and Central Asia, told InfoMigrants that juvenile migrants, particularly those who are unaccompanied or separated from their loved ones, are stripped of stability and family, factors which are crucial to nurturing development.

However, Knutzen stressed that children need not be defined by the trauma that they experience.

"Children are profoundly resilient," she said. "That doesn’t mean their experiences aren't life-altering -- they are. Adverse childhood experiences leave deep impacts. But when a child has access to an environment where they can feel nurtured, their ability to recover, lead productive and healthy lives is very profound."

"History is full of children who came through adversity and went on to make extraordinary contributions to the societies they joined," Knutzen added.

Healing, Knutzen explained, is a process that unfolds gradually, through sustained access to care, through relationships with trusted adults who have their best interests at heart, and through consistent routines—such as "the small but vital anchor" provided by drop-in centers.

"We know from research and practice that one of the most protective factors for any child is having a caring adult looking out for them," she said. "And for many unaccompanied minors that’s often missing. Drop-in centers can play a part in filling that gap."

Knutzen acknowledged, however, that drop-in centers are just one piece of a larger puzzle. "They have to be part of a broader ecosystem. We need long-term support structures with essential basic services in place."

Alongside support for medical, legal, and welfare needs, Halte Humanitaire Diderot also organizes cultural activities, like museum visits or city tours, which are always quickly filled.

Such activities, in tandem with basic services, contribute to healing and rebuilding something else that unaccompanied minors are stripped of: their capacity to dream.

As one 15-year-old who was surveyed said, "I love France; it’s the country of my dreams. I dream of studying -- I need it. That’s my goal."