An EU proposal to potentially send certain failed asylum seekers to return hubs in third countries such as Uganda has led to some recent backlash amid growing concern over the rule of law and the human rights record in these destinations. With a similar plan by the UK government having failed in Rwanda last year, there are mounting questions over the legal implementation of such offshoring schemes.

The European Union is exploring ideas to establish hubs to process failed asylum seekers outside the bloc, with European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen recently backing plans to overhaul the EU's overall approach to migration to this end.

Last month, the EU announced that only about one in five failed asylum seekers in the 27-country bloc could actually be successfully deported, oftentimes due to the lack of feasibility of their return to their home countries.

Even if it is established that they may not face persecution in their countries of origin, many failed asylum seekers remain in EU nations for years, often due to the lack of return agreements with their home countries. Many of them eventually gain the right to stay in the European Union solely on the basis of their prolonged presence there.

Now, the EU wants to start closing loopholes that enable such a low rate of deportation to be enforced.

Read AlsoEU seeks to accelerate return of migrants

Major changes in EU law needed

A slew of suggested measures are yet to be passed by the European Parliament and Council, but with strong support from many member states and no need to address each national government individually, the bloc looks set to redefine its approach to asylum.

Under current law, the EU can only send rejected asylum seekers back to their country of origin, or to another EU country where they have a prior record as stipulated by the so-called Dublin regulation.

The bloc would therefore need to change specific laws such as Article 3 of the EU Return Directive, which stipulates that the forced return of rejected asylum seekers is only possible to their country of origin, a transit country, or a country where the returnee has family ties or a residence permit.

The proposed change in law could however also be found to be in breach of the European Convention on Human Rights, which supersedes EU law, if it is brought before the European Court of Human rights (ECtHR).

Read AlsoNew EU regulations: deportations, return hubs, detention, bans and more

Amnesty: 'EU wants to deny refugee protection'

The EU hopes to succeed in changing the law to allow rejected asylum seekers to be deported to return hubs in third countries -- until such time that they can safely be deported back to their countries of origin.

As part of the same set of reforms, the EU also wants to make asylum decisions made in one EU country binding across the bloc, which could still lead to cases and scenarios where a person might be deported to a third country even if their case was rejected in an EU nation that doesn't have such bilateral deals with third countries.

Under the proposal, the EU would not build or manage the return hubs but instead would allow its member states to negotiate with third countries willing to take rejected asylum seekers directly.

Amnesty International, meanwhile, has criticized this push for offshore return hubs, saying that EU governments are "denying [their] responsibility for offering refugee protection."

Human rights record of host countries

The idea of allowing for such return hubs to be created by individuals EU member states appears to raise certain questions pertaining to international law reaching beyond the bloc as well; since the EU itself would not be involved in the creation of the hubs but would only offer to legal framework for member states to approach third countries in this matter, it could leave the EU itself exonerated while creating trouble for member states.

The European Commission says that new rules will "make it legally possible for an EU country to make an agreement or arrangement for return with a third country that respects international human rights standards and principles in accordance with international law."

However, with certain countries already being suggested by some EU member states as potential host nations for these return hubs, there have already been doubts about the same "international human rights standards and principles" which Brussels says it will require to be respected as the basis of reaching such deals.

Uganda: negotiations underway with the Netherlands

One of the potential countries that has repeatedly been highlighted in this context is Uganda, after the Netherlands' Prime Minister Dick Schoof announced last year that plans to explore Uganda as a return hub for migrants from Africa were already underway.

However in some respects, Uganda is already widely known for its poor human rights record and issues with the rule of law; for example, since the introduction of a 2023 law, the African nation prescribes lengthy prison sentences for members of the LGBTQ+ community, and even keeps the death penalty in the books for repeat offenders.

On March 30, the US-based Global Press Journal published an article, highlighting the case of a lesbian from Uganda who fled to the Netherlands after the country's Anti-Homosexuality Law was enacted two years ago. Now, she has to fear being sent back after failing her asylum application twice, with the Netherlands seen to be cosying up to Uganda.

The case is now under review as part of the appeals process -- but if the Netherlands were to sign an agreement specifically with Uganda to return failed asylum seekers there, the woman's life might be in danger.

This comes after a number of allegations of Ugandans "faking" their sexual orientation in the Netherlands in a bid to obtain protection.

While there is no official confirmation by Ugandan authorities on how far the negotiations on establishing a return hub for the government of the Netherlands might be, an official working Uganda's Ministry of Foreign Affairs told the Global Press Journal on the condition of anonymity that the foreign minister and the Dutch ambassador had met in January to discuss the plan.

Read AlsoNetherlands: Coalition government agrees on tough measures against asylum seekers

In the middle of multiple conflict zones

Uganda has been facing an uphill battle in trying to establish greater economic equality among its citizens, with at least 20 percent of the country believed to live below the poverty line despite recent growth.

A deal with a European partner like the Netherlands could mean favorable economic circumstances, such as better trade tariffs or more development aid for the country's coffers.

However, with a brutal conflict raging in the neighboring Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda could also see an influx in refugees at its western borders, as parts of the DRC are now described as akin to a civil war.

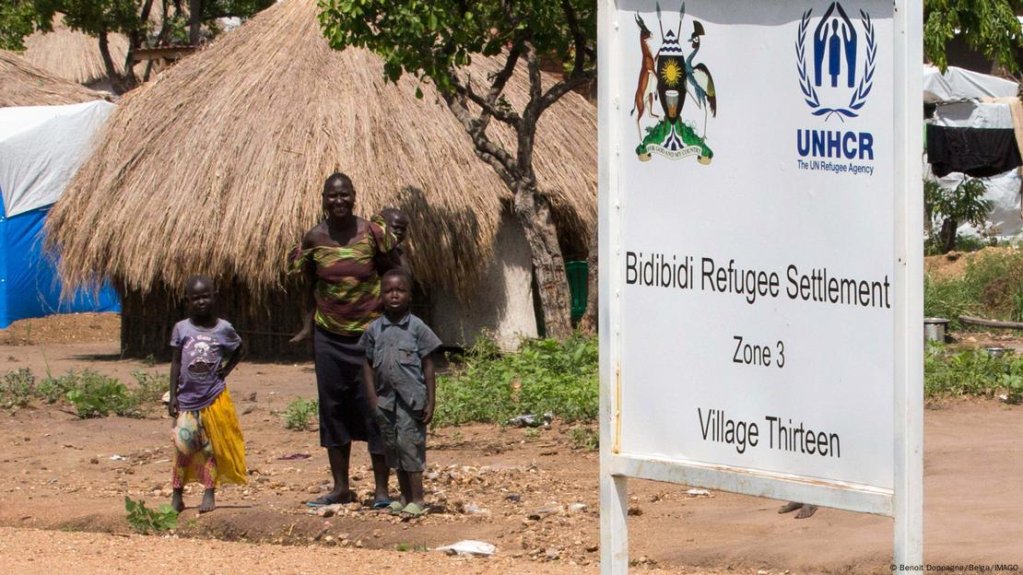

Uganda already hosts more refugees than any other nation in Africa, according to UNHCR, with the majority of the 1.7 million displaced people in the country coming from the DRC and from South Sudan, where in recent weeks civil unrest has also led to a spike in tensions.

Read AlsoNetherlands revives plan to send failed asylum seekers to Uganda

Albania: Italy's empty migrant warehouse

But there are attempts to outsource migrants to third countries much closer to the EU, which have run into costly legal and logistics hurdles.

Italy finished constructing two migrant centers in Albania, where male migrants intercepted by Italian boats at sea were intended to be detained and processed.

However, following a series of legal challenges and domestic issues over the power of Italian judges, the facilities remain empty for the time being, with the EU and others observing the developments in the Italy-Albania deal closely.

The centers, which are estimated to have cost 700 million US dollars over five years, were supposed to host a batch of 3,000 migrants per month.

Read AlsoIs Italy's model for offshoring migrants doomed to fail?

Rwanda: a failed — and costly — UK experiment

From 2022 to 2024, the UK also attempted to establish an offshore migrant center in Rwanda under its previous government.

After leaving the European Union in 2020, Britain tried to clamp down on irregular migration by creating further disincentives for potential migrants to seek to come to the UK -- including the threat of possibly being deported to Rwanda.

That scheme also ran into multiple legal hurdles and was eventually abandoned last year after general elections. In addition to human rights concerns in the African nation, the Rwanda plan was also criticized for being costly, with the UK's National Audit Office estimating that it would cost the British taxpayer more than 750 million US dollars to send an initial 300 people to the African country.

Read AlsoUK:The end of the Rwanda plan