More than 240,000 Sudanese refugees have arrived in Libya since fresh conflict broke out in the country in April 2023. Some of those who arrived have recounted their experiences of starvation, rape, murder, slavery and organ harvesting in the North African country, as they wait to try and cross to Europe.

Starvation, rape, murder, slavery and organ harvesting are all experiences recounted by Sudanese nationals who fled to Libya after fresh conflict broke out in their country in April 2023. That's according to a new report from the news agency Reuters, published on March 13.

Since the war between government forces and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces broke out two years ago, tens of thousands of people have been killed in the country.

It is estimated that at least 12 million Sudanese nationals have been displaced due to the conflict, with the majority being displaced internally within the country.

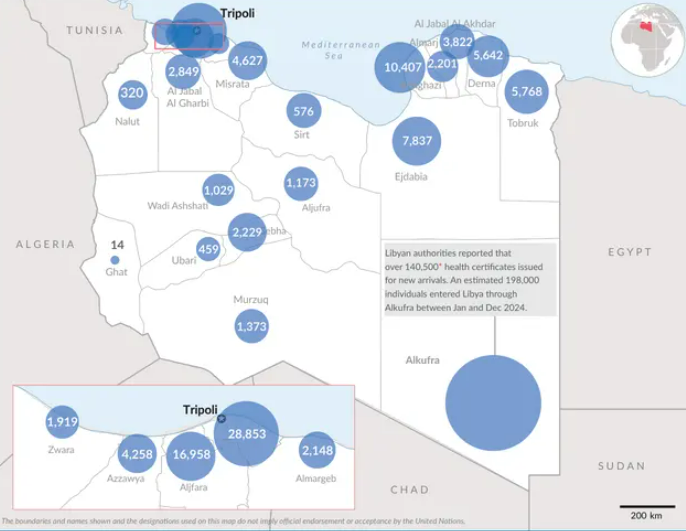

However, there is also a considerable number of people who have fled to neighboring nations like South Sudan, Chad and more than 240,00 on to Libya, according to the latest estimates from the UN Refugee Agency UNHCR, that released a report on February 9 this year.

Read AlsoUNHCR scales up response to Sudanese refugees coming to Libya

Horrors on the journey

A 17-year-old Sudanese refugee from the city of al-Fashir in Sudan's North Darfur state spoke to Reuters using the pseudonym Farid, recalling some of the extreme horrors he had witnessed in Libya in particular.

On his migration journey, Farid recalled passing through southeastern Libya — a part of the country that has recently made headlines over a series of severe human rights abuses there.

Mass graves containing the bodies of scores of migrants were discovered in the area just weeks ago near the settlement of Kufra.

Read AlsoLibya: UN confirms 93 bodies exhumed from mass graves

'Many are dying'

Farid told Reuters that there were hundreds of other Sudanese war refugees seeking assistance from Libyan authorities there like he did.

Instead of the help they are seeking, Farid said he had seen cases of deliberate starvation at the hands of criminal tribal gangs in the region.

"(S)o many are dying in al-Fashir. They are starving," he said, highlighting that warring tribal factions steal and sell international food aid.

Farid also remembered not only witnessing starvation deaths but also deliberate murders under incredibly brutal conditions.

"I saw a girl being beaten and raped. They killed her and left her on the street," Farid recalled.

"The mother took her body back to Sudan. She'd rather die in the war than stay in Libya."

Read Also'Unimaginable horrors' on migration routes to Europe, UN report

Organ harvesting in the desert

Farid also shared his own story from Kufra, where he had to sleep rough, starving until he was eventually given a mattress to sleep on and a little food by Libyan authorities. However, in return he was forced to work long hours collecting plastic waste for recycling — without being paid for this.

When he raised a complaint, he says he was told that if he were to cause any problems, he would be sold to one of the rival militias in the area.

"Kufra is a tribal area. And we are slaves in their land," Farid told Reuters. "They make us fight for them or sell us into forced labor. If you refuse, they can take your organs and bury you by the road."

According to a report in 2021, published by the private intelligence firm Grey Analytics in the UK, there are "endemic" levels of organ harvesting activities carried out by criminal gangs in Libya, mostly targeting Black African migrants in particular.

"The victims are often first sold into slavery and organ harvesting happens after. This well-organized process including brokers, traffickers, physicians, hospitals, shippers and end-users. In the case of trafficked organs from Libya, the end-users are the surrounding Arab countries. However, also countries such as Israel, the United States and Canada, and the European countries," the report by Grey Analytics said.

Read AlsoLeft to be forgotten: EU accused of being complicit in migrant 'dumping' in North Africa

'The sea will not torture you'

According to UNHCR, Sudanese refugees in Libya account for nearly three quarters of all refugees in the country.

Hundreds more are believed to arrive each day, while dozens are believed to die too, reportedly often under mysterious circumstances.

Farid himself eventually did manage to escape the brutality of Libya's lawless desert regions, making his way to the north of the country and boarding a migrant boat to Europe.

The dinghy he was on was picked up by the Humanity 1 private rescue ship, as the rubber vessel, overloaded with 70 people, started to take on water off the coast of Libya. Most of the people he was traveling with were also unaccompanied minors who had fled Sudan's war.

Read AlsoTens of thousands of migrant testimonies reveal dangers of land routes in Africa

'It is like a game of snakes and ladders'

Another young Sudanese man, 19-year-old Ahmed* said that making your way through the maze of Libyan prisons towards the Mediterranean coast felt like a brutal game of "snakes and ladders" at time to him.

"There's a chain of detention centers, that you work your way through from Kufra in the south to Zawiya or Ain Zara in the north. You have to pay for your release each time. If you get caught again, you start over, like a game of snakes and ladders."

Ahmed also described actually crossing the Mediterranean as a "small boat lottery," reported Reuters. According to him, the type of boat a migrant might be allowed to board, depends on the sum of money you are able to pay.

Sudanese and Eritreans often had less money at their disposal to pay for a trip, and consequently would have less chance of a successful crossing in a safer boat. Egyptians and Syrians tended to be able to pay more for the crossing and so might end up on a ship that made the crossing successfully.

According to Ahmed, some crossings can cost as much as 15,000 dollars (about 13,790 euros).

Like Farid, Ahmed also ended up eventually crossing to Italy. Despite nearly dying on several occasions during his journey — especially when he came closest to death at sea — Ahmed told Reuters he would risk his life all over again.

"Dying at sea is better [than dying in Libya]. The sea will not torture you."

*Name changed by Reuters to protect his identity

This article was partly based on a Reuters feature written by Sean Columb