The European Commission is expected to unveil a series of reforms to the EU's overall migration policy, with a sharp focus on upping the numbers of returns for failed asylum seekers who have been ordered to leave EU member states.

"I aim to make it possible for member states to think about new, innovative ideas, including return hubs," EU Commission chief Magnus Brunner said during a closed-door briefing on Monday, March 10, reported the Europan news platform Euractiv on Tuesday.

Brunner believes the issue of returns is "existential," to the bloc. "We try to give people the feeling that they have control over what is happening in Europe," the Commissioner told journalists, reported Euractiv. He stressed that if the democratic center parties do not address the issue, "we will lose the trust of our citizens altogether." More details are expected to be announced later on Tuesday.

Currently, fewer than 20 percent of migrants who fail their asylum applications at all legal instances, and are therefore told to leave the EU, actually leave the bloc, remaining in Europe instead.

To counter this, the European Union wants to introduce changes, especially to its migrant return system, to make sure migrants have fewer incentives to come to the EU in the first place and have a more unified approach to an issue, which is affecting all member states, albeit to varying degrees.

"We want to put in place a truly European system for returns, preventing absconding, and facilitating the return of third-country nationals with no right to stay," European Commission chief Ursula von der Leyen said about the developments this week.

The new legislation will build on existing rules, which have remained unchanged since 2008. In order to bypass national implementation debates, the laws are intended to be rolled out as a regulation, which means that they will be applicable and binding in all member states.

'Innovative' solutions to pan-European phenomenon

The move to tighten the EU’s returns system began last year in earnest in October. Several EU member states called for urgent new legislation to be introduced to counter overall irregular migration.

Led by the governments of Sweden, Italy, Denmark and the Netherlands, draft legislation to speed up returns and increase the volume of deportations was presented to the EU Commission as part of a push to suggest more "innovative" ways to address migration.

Several other governments have since also voiced at least tacit support for many of the proposals therein. Others have started rolling out their own new policies to reduce migrant arrivals, like Germany's establishment of specific return centers along the Polish border.

The EU has taken all this to heart and has worked out how to change EU laws accordingly to react to a changing political and social landscape across the bloc.

Read AlsoAsylum seekers in the EU: Six things to know about 2024 report

Closing national loopholes and coordinating returns more centrally

The regulation will reportedly propose a new "European return order," and mutual recognition of return decisions among member states. This means that if an asylum applicant fails in one EU country and then moves to another EU country to try their luck there, their initial rejection in the first country should be recognized as sufficient grounds to deport them, rather than beging able to open another case in the second country.

However, the draft also says this mutual recognition paragraph will not be mandatory, which would allow individual members to take different decisions on the same cases, where they deemed it necessary.

Among the more controversial suggestions presented to the EU and now included in the new regulation, there’s also the divisive idea of creating so-called "return hubs" situated outside European Union territory, where failed asylum seekers could be sent prior to their ultimate transfer home.

This way, rejected asylum seekers can no longer fall through the cracks within any given EU country and go into hiding, eventually claiming some legal form of being allowed to remain there following potentially years of a 'de facto' presence in that country.

Under EU rules to date, migrants can only be transferred to their country of origin or a country they transited from and only after being served a deportation order at least one week prior to their deportation date.

The new regulation will do away with the mandatory deportation notice serving period and leave it at the discretion of national governments to decide on how much forewarning — if any — they wish to give people who are to be returned to their home countries or even to one of the return hubs, which are still under discussion.

Read AlsoFrance calls for Europe to co-operate on expulsion of undocumented migrants

Return hubs: Rwanda under a different name?

It is unclear at this point where exactly these return hubs could be built or when the move to erect these structures will go ahead. Less than a year ago, the UK abandoned its plans to deport potential asylum seekers to Rwanda following a change in government.

Prior to that, the Rwanda scheme had run into multiple legal hurdles, including being taken all the way to the European Court of Human Rights, to which Britain is still a signatory even after its departure from the European Union in 2020 (commonly referred to as 'Brexit').

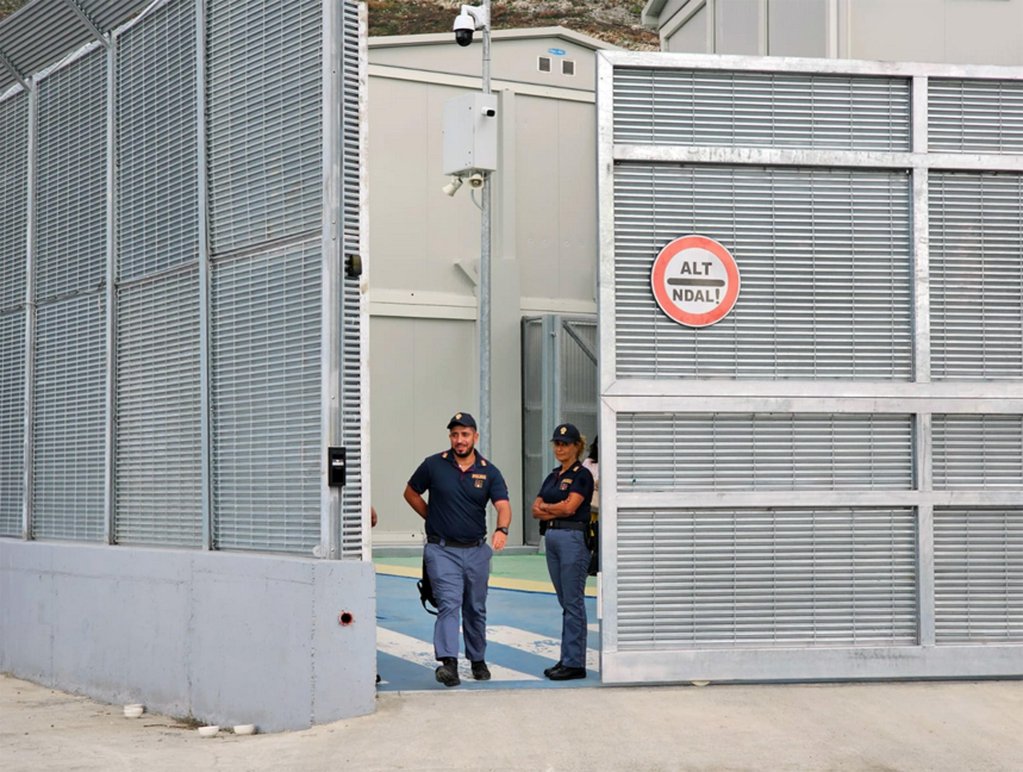

Last August, Italy opened two asylum processing facilities in Albania, which is not an EU member. The facilities are designed to host only non-vulnerable able-bodied men intercepted at sea outside Italian territorial waters by Italian patrol boats, whose nationality would make them unlikely to qualify for asylum in the first place.

However, Italy has also encountered multiple legal hurdles and is yet to successfully make use of the facilities, which are being operated at an estimated cost of 160 million euros a year for the next five years.

Previously, suggestions of building migration hubs in northern Africa were also floated by national governments as well as by certain factions within the European Commission but have been abandoned in lieu of the 2016 EU deal with Turkey, under which Turkey is asked to host migrants on its soile and prevent them from reaching the EU, in exchange for six million euros.

That scheme has only had limited success, however, as migrants and refugees continue to manage to make their way to Europe from Turkey by both land and sea.

Detention possibilities

The EU's move comes after several European governments have shifted to the right or even the far-right in recent elections, winning those votes on anti-migrant platforms. As geopolitical and economic problems worsen, public opinion is turning increasingly against migration, and the EU is trying to maintain its integrity while responding to these social developments,

"We have tried other systems for many years, it doesn't work," Sweden's migration minister, Johan Forssell, told the AFP news agency. "If we are not going to do the return hubs, what will we do instead is my question?"

"We are 27 different member states that all have the same challenges, but we cannot have 27 different return centers," Forsell added, highlighting the importance for a unified returns system via these hubs outside the EU.

Other aspects of the new regulation include tougher rules for individuals considered to pose security threats or those deemed to be likely absconders from deportation orders. Such individuals will be allowed to be detained at the discretion of national government guidelines for up to 24 months or in the case of serious security risks, such as people involved in terrorist networks, the detention could take as long as necessary to ensure the deportation is carried out.

This means that in isolated cases of terror suspects, people could be detained — either in the country where they sought asylum or in one of the return hubs outside EU territory — until such a time comes that their country of origin is safe enough for them to be returned.

Further to this, failed and deported asylum applicants can now face entry bans to the EU of up to 20 years in extreme cases.

Previously, these bans were capped at five years.

Read AlsoSweden hints at introduction of EU migrant 'return hubs' in near future

Legal challenges ahead?

However, the new regulation is not without controversy, as some of its suggestions entail untested methods, such as establishing migrant return hubs in third countries outside the bloc.

Several rights groups have meanwhile already voiced concerns against the proposal, saying that severe human rights abuses could follow.

"This new proposal will be harmful and confirms the EU’s obsession with deportations, rather than considering measures that could truly foster social inclusion and regularization," said Silvia Carta, Advocacy Officer at the Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants (PICUM).

"We can likely expect more people being locked up in immigration detention centers across Europe, families separated, and people sent to countries they don't even know," she added.

Olivia Sundberg Diez of Amnesty International meanwhile said that the concrete suggestion of building return hubs outside the EU will "likely run into a slew of legal challenges."

"We can expect drawn-out litigation, probably costly centers sitting empty and lives in limbo in the meantime," she continued.

However EU chief von der Leyen meanwhile stressed that while the bloc seeks to take tougher action against people who remain in the EU illegally, especially those who might pose a security risk, international law and fundamental human rights would be adhered to under the new regulations.

Read AlsoEU seeks to accelerate return of migrants

with AFP, dpa, KNA