An Austrian study has found that refugees face greater housing instability than other categories of migrants. They tend to move nearly four times more than other migrants, "signaling greater instability."

The study carried out by the Complexity Science Hub in Vienna, Austria, and published in Springer Nature, suggest that both gender and country of origin "significantly influence this mobility." Researchers say that although their findings were based on Austrian case studies, they are "globally relevant, especially in light of the rising number of migrants worldwide."

Around 20 percent of people living in Austria today are international migrants, states the study. Around 276,800 of those are refugees and asylum seekers. In comparison, Germany has around 15.7 percent and the UK and France 14 percent.

The researchers decided to look at the housing situation of refugees in particular, because they felt that this area of refugees' lives was under-studied. More data has been gathered about their integration into the labor market or the healthcare system.

Read AlsoAustria: Freedom Party's victory continues political shift to the right in Europe

Study looked at movement over the course of a year

The study looked at all registered changes of address from non-Austrian nationals who had their primary residence in Austria, at least temporarily between November 2022 and November 2023. The data was provided by Austria’s Interior Ministry.

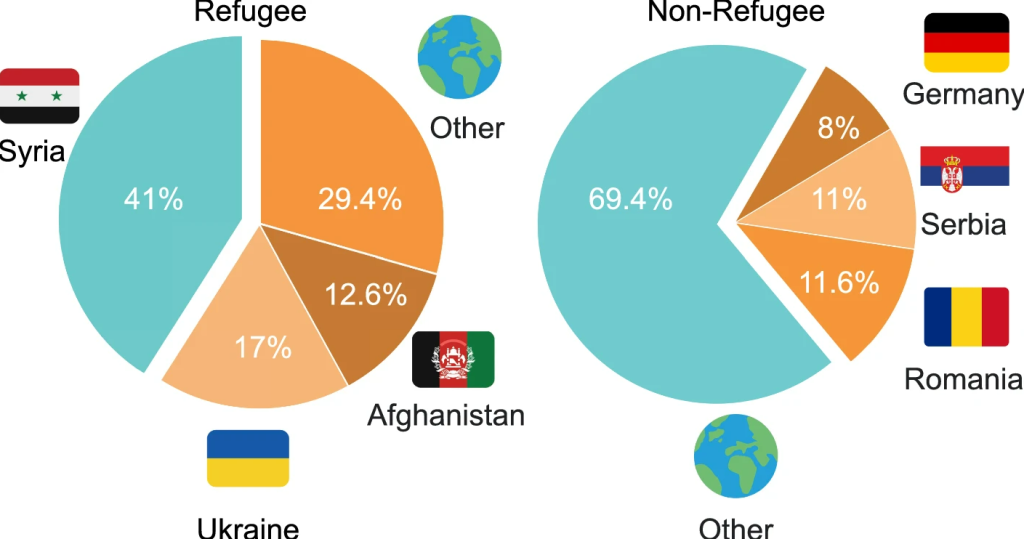

All in all, the study comprised 1.6 million people, 17 percent of whom were refugees and 83 percent of whom were migrants. The definition of migrants in this case is understood to mean "people who came to Austria voluntarily and are not threatened by persecution in their home country."

On average, researchers found that refugees moved 3.8 times more frequently than other migrants, even when they came from the same country. Almost 60 percent of migrants did not change their address within the year studied, whereas only 33 percent of refugees remained in the same address for that year.

The researchers admit that sometimes changing residence could be linked to an improvement in your housing situation, a personal choice, or a job change. However, they underline that the longer you live at one address, the better it is and the more crucial for building connections to the place and integrating into the local community.

Moving is stressful

Moving is recognized as a stressful process for most people, even when it is a free choice. The researchers found that frequent moves within a year "can lead to several challenges, including financial strain, difficulty accessing education and healthcare, and a lack of stable relationships within neighborhoods."

Ola Ali, one of the PhD researchers on the project, says that understanding the degree of stability a person has in their housing situation therefore is key to helping host societies assess the degree of integration and support a refugee might need to settle in to the new cntry.

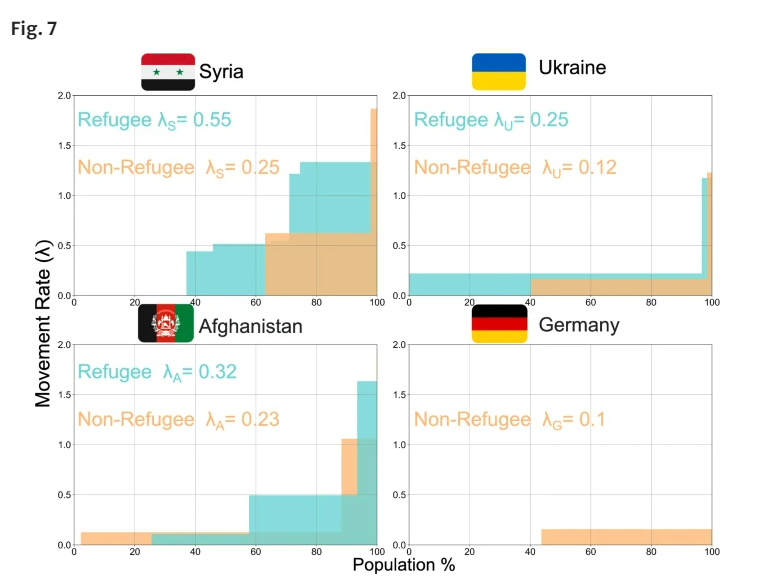

Interestingly, it was found that male refugees changed address almost twice as often as female refugees. The country of origin also influenced the degree of instability. "Refugees from Syria change their residence most frequently. Refugees from Syria move the most often, relocating on average 0.55 time per year –2.2 times more often than Ukrainian refugees, 1.7 times more often than Afghan refugees, and almost 5.5 times more often than migrants from Germany," explained Ali.

Of the people that relocated within the same district, labeled "churning movers" by the researchers, 41 percent were from Syria, 17 percent from Ukraine and 12 percent from Afghanistan.

Read AlsoEU top court rules Afghan women are a persecuted group

Frequent movers are deemed more vulnerable

This group of "churning movers," states the study are often more vulnerable. Often the frequent moves are because of eviction, or other forced moves and are more frequent in low-income households, or families on the edge of homelessness.

Long-distance moves are also associated with lower school performance, the loss of friends and additional challenges for adaptation, according to a study by Cordes et al in 2019 that the study cites.

The authors suggest that multiple moves and the unstable populations they include could lead to "residential segregation and the spatial concentration of social issues like crime," citing a 2008 study by Clark and Fossett.

Ali believes that some of the moves may be linked to the legal status assigned to the respondents on entering Austria. Most Syrian refugees were immediately granted asylum status, and almost all Ukrainian refugees are classified as displaced persons. In Austria, migrants are classified into 11 different legal statuses, ranging from recognized refugees to "foreigner" -- a person who has arrived in the country and is not applying for asylum. That 'foreigner' becomes a "resident with a residence permit," as soon as they have the right to stay in Austria.

In the case of asylum seekers, depending on their stage in the process, they could be classified as asylum seeker, approved asylum seeker, entitled to asylum, eligible for subsidiary protection, eligible for humanitarian residence permit or displaced person.

Many of the refugees tended to migrate towards Austria’s capital Vienna, perhaps because of the hope for better job prospects, or more diverse communities in the country’s bigger cities. The refugees in Austria are also more often male than female (55 percent male), and tend to be younger than the non-refugee population.

Refugees and displaced people numbers rising

The co-leader of the Human Migration Research Group at CSH, Rafael Prieto-Curiel, points out that according to UN data, at the end of 2023, the number of forcibly displaced people in the world reached a record high of 117.3 million. In less than a decade, these numbers have doubled, mainly due to a rise in violence and conflict in the world.

The world’s population is also increasing. Projects suggest that by 2050, there will be 20 percent more people in the world than today. Climate change causing water shortages, floods, food insecurity and other natural disasters are also pushing more people to migrate.

In the paper, the authors point out that more and more people are becoming displaced due to violence. According to two studies in 1951 and again in 2017, researchers found that the number of refugees increases by 0.4 percent for every year of conflict, thus they expect the number of refugees will probably increase within the next decades too.

Given this trend, understanding how to stabilize these populations on the move is more important than ever, thinks Prieto-Curiel. “With the global number of refugees rising, understanding the complexities of refugee populations and their living conditions is essential for helping them settle in a new country.”

Ali adds she hopes the study will highlight that not all migrant populations can be treated the same and that understanding these differences and then coming up with solutions for them "could have a significant impact."

Read Also'Sudan is trapped in a nightmare' – extreme violence drives record refugee exodus, UN says

Looking to the future

The paper details some of the particular challenges faced by refugees in their host societies. From labor market integration to intercultural dialogue. Many refugees, found the authors, "face significant delays securing their first job compared to other non-refugees, primarily due to restricted job market access during the asylum process." They also often face barriers to healthcare access and "exhibit lower self-assessed health in Austria, as reported by predominantly female refugees from Afghanistan."

Citing a 2015 study, the authors conclude that "initial residential instability breeds further residential instability and, with that, instability in schooling choices, work choices, as well as instability of the social networks that refugees can build."

They argue that frequent moves place a higher financial burden on refugees, suggesting that refugees should be targeted with financial support and interventions to alleviate these challenges. To illustrate this, the study underlines that 60 percent of people from Ukraine in Austria receive welfare support, and they do not move as frequently as refugees from Afghanistan or Syria. Just 20 percent of Syrians receive welfare support in Austria and just 5.9 percent of Afghans.

"In the absence of opportunities to thrive in host nations, refugees may become marginalized groups, an undesirable outcome for both the refugees and their hosts," point out the study authors.

To avoid that in the future, they underline the need to understand the reasons behind the moves more, as well as changing policies, so that families who might be more vulnerable to frequent moves could be supported better before their lives become so unstable that they are forced to move again and again, becoming ever more unstable members of society in the process.