Seeking asylum in Cyprus, Poland and Bulgaria is becoming increasing difficult given the number of pushbacks at the external borders of the European Union. InfoMigrants spoke to migrants about their experiences.

John, a 34-year-old Nigerian, arrived in the Aglantzia camp located inside a United Nations (UN)-controlled buffer zone in Cyprus last July. Three months later, he was still living in the camp. Like dozens of other migrants from Cameroon, Sudan, Syria and Afghanistan, John sought to apply for asylum when he arrived in the southern part of the island. Yet he was pushed back by the police and brought to the camp improvised by the UN along with the other migrants he was traveling with.

When InfoMigrants visited the camp at the end of August, the migrants recounted a similar scene. "When they [the police officers, editor's note] found us, they forced us to sit on the ground while pointing their guns at us. Then they ordered us to return to the north," said Ibrahim from Sudan. After several hours of walking, the exhausted migrants finally stopped in the buffer zone.

On the divided island of Cyprus, many migrants want to reach the southern part to have access to the EU asylum system. The Turkish-controlled north lacks a proper asylum system. The buffer zone is located between the two.

John, Ibrahim, and the other migrants in the camp had all been victims of pushbacks by the Cypriot authorities in the south. Pushbacks “are various measures taken by States that results in migrants, including asylum seekers, being summarily forced back to the country from where they attempted to cross", according to the special rapporteur on the human rights of migrants from the UN human rights office OHCHR. When migrants are pushed back, they are denied the right to ask for asylum or international protection -- their protection needs are not assessed properly.

Because of this, pushbacks are generally considered illegal. They go against the "principle of non-refoulement" contained in Article 33 of the 1951 Refugee Convention: “No Contracting State shall expel or return […] a refugee in any manner whatsoever to the frontiers of territories where his life or freedom would be threatened". The principle of non-refoulement is also part of the European Union's Charter of Fundamental Rights.

The UN Refugee Agency UNHCR has stated that, "no exception is permitted to Article 33 of the 1951 Convention or to any other non-refoulement provision under international law."

Nearly 9,000 pushbacks in eight months

Thousands of migrants seeking protection have been forcibly expelled at EU’s external land borders for decades. These practices continued for years after the 2015 European migrant crisis, often accompanied by various forms of violence and humiliation. They often occurred along the Balkan route or in the Evros region on the border between Greece and Turkey.

More recently, pushbacks have increased at other EU entry points, like in Cyprus and Poland. Some 9,000 pushbacks were recorded between December 2023 and July 2024 at the Polish border with Belarus, according to statistics collected by the organization 'We are monitoring' (WAM).

People using this migratory route and seeking protection have therefore been prevented from applying for asylum on an almost daily basis since the border crisis with Belarus began in August 2021, say non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

Read AlsoHow do I apply for asylum in Poland?

Azzedine, originally from Sudan, told InfoMigrants that he was stopped by Polish border guards every time when he tried to cross the border. He claims that he applied for asylum each time. "The border guards beat [migrants], break phones and spray us in the eyes with gas," he told InfoMigrants. "I never thought I would have this experience. I just wanted to escape the war and find a safe country."

After wandering for three months in the Belarusian forest, Azzedine was finally rescued after his ninth crossing by a local NGO.

‘The police took our phones, our belongings and our money each time’

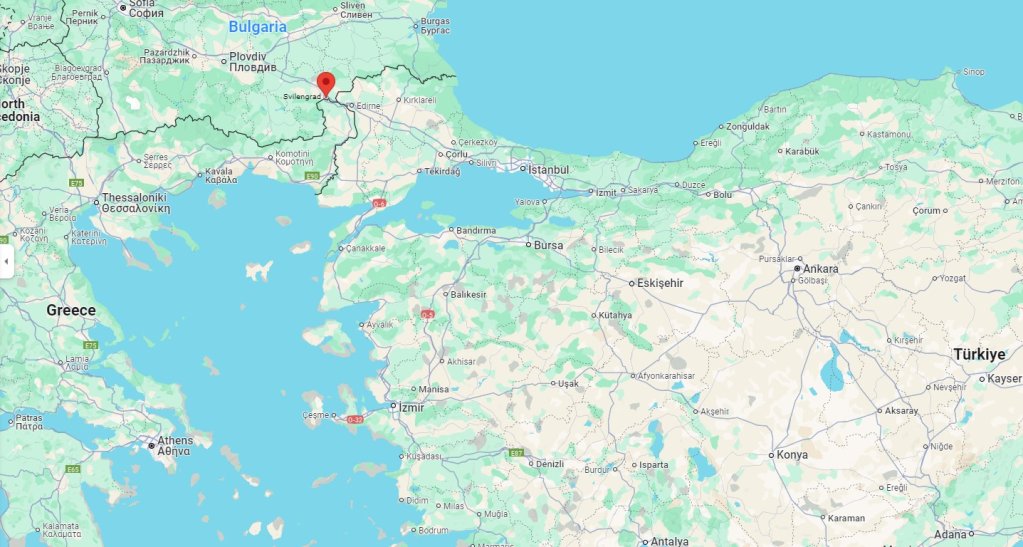

Numerous pushbacks also occur at the border between EU member state Bulgaria and Turkey. Border guards in the region reportedly often resort to violence. Migrants have been “forced to swim back to Turkey", forcibly stripped and bitten by the dogs of the Bulgarian border guards, according to a 2022 report written by an officer of EU border agency Frontex that was made public by investigative journalists. NGOs have condemned the growing number of pushbacks, and the European border protection agency Frontex is well aware of the upsurge, according to an investigation by the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN).

InfoMigrants met a group of four young Moroccans in June in the small town of Svilengrad, near the border with Turkey. Amine*, 24, said he had been driven back five times. The others, aged 22 to 30, had experienced between two and three pushbacks during which, "the police took our phones, our belongings [and] our money each time", said Amine. The young man added that the police also took away the migrants’ clothes and their shoes.

The Bulgarian Ministry of the Interior published a report in April 2024 recording 10,041 cases from January to April 2024 of migrants "returning alone to the interior of a neighboring country" following the action of the border police -- which corresponds to "pushbacks".

'No go zone'

Despite the many reports, testimonies and investigations condemning pushbacks and pointing out their illegality, they are still taking place. For Matthieu Tardis, a researcher specialized in immigration, the lack of reaction from European institutions gives the countries in question the freedom to act as they wish. "The European Commission, which guarantees compliance with EU treaties on asylum, condemned these practices a few years ago. We hear much less disapproval today; it has lost much of its influence over its members," he said.

Countries are also acting discreetly, increasing the number of off-limit areas to civilians. "In order to carry out these pushbacks, states rely on various strategies. Poland, for example, has twice declared the border area a 'no go zone', forbidding NGOs and journalists from operating in the zone. This context obviously makes the 'pushbacks' less visible, and leads to a certain banalization of the practice," said Tardis.

Read AlsoPoland: 'Things are getting worse at the border', say activists

The stance of Brussels on "pushbacks" is also ambiguous. The Asylum and Migration Pact adopted by the European Parliament in April 2024 sets out a new approach which will be less protective for asylum seekers at the borders, especially in the event of "instrumentalization" of migratory flows by a country or a third party. This is the case on the Polish-Belarusian border: The EU has said that the migratory flows are knowingly organized by the Belarusian leader Alexander Lukashenko.

The EU pact also toughens the conditions for obtaining asylum at the borders. A "rapid" asylum procedure -- which has been have strongly criticized by NGOs -- will now apply to all nationals from countries for which the average rate of recognition of refugee status in the European Union is less than 20%, such as Morocco, Tunisia, or Bangladesh.

These individuals will be considered as not having entered European territory. "They would therefore be kept in a legal fiction of non-entry even though they were on the territory of the Member States", wrote La Cimade in a report published last June. According to the association, the provision ratifies the principle of non-refoulement at an institutional level.

*The first names in this article have been changed

Read AlsoLatvia: Afghan migrant smuggled from Belarus dies of hypothermia