The German government is keen to attract foreign workers to fill gaps in many branches, including in gastronomy. It has created new speedier processes to try and address this need, but some restaurant owners told German public broadcaster ARD recently that the processes are not as easy, or fast, as they were promised.

"It is just crazy. We are facing never-ending problems trying to employ good cooks, and good waiters, and I just don’t get it anymore, I don’t know where to turn," says restaurant manager Gregor Lemke in Munich. He is the manager of the Klosterwirt an der Frauenkirche in Munich, and director of the inner city restaurateurs organization (Verein Münchner Innenstadtwirte).

The percentage of foreign workers employed in this branch is relatively high, about 80 different nationalities are present in one of the biggest pubs and restaurants in Munich. But some restaurant owners are finding that even the new speedier bureaucratic processes are standing in their way and preventing them from taking on employees even when they have found them.

Long hours, high stress and relatively low pay mean the sector is finding it more and more difficult to find Germans ready to work there. But for many migrants hoping to enter Germany by legal means, the sector is potentially attractive. However, between their interviews and arrival, months, and even years can pass, say restaurant owners.

Read AlsoGermany takes steps to attract skilled Indian workers

'It is threatening to delay the opening of our restaurant'

Lemke was speaking to documentary makers working for Germany’s public broadcaster ARD. They began speaking to some of the protagonists in 2022 and followed up with them over the course of the next two years.

The documentary took the cases of three different restaurants, two in the southern city of Munich and one in the western city of Cologne. All the managers at these establishments wanted to employ foreign workers legally. But their attempts had become mired in bureaucracy and process.

"It is threatening to delay the opening of our restaurant," explained businessman Mikko Bayer in Cologne.

In 2023, ARD reports, there were 450 applications via one of the Foreign Skills Approval Offices (IHK Fosa) for skilled migrant labor from outside the EU. Only 98 of those were recognized. 78.2 percent were refused, or only partially recognized.

Restaurateurs Mikko and his partner Sacha Bayer were hoping to bring four Indonesian cooks to Germany legally, and that process also found its way to the IHK Fosa's desk. In Munich, Lemke was trying to employ a Russian cook who had fled Russia because of its invasion of Ukraine. Also in Munich, fellow restaurant manager Oliver Wendel, from the Augustiner am Platzl restaurant, was struggling to engineer the return of one of his "best workers," a waiter called Ashti Salam Abdi.

Sent back to Iraq

Ashti left Erbil when he was just 13, reports ARD. He is from a Yazidi family and had been working and paying taxes in Germany since he was 17. But as the documentary began, his asylum request had been refused and his right to stay in Germany brought to an end. At the age of 20, he is asked to leave his family in Germany and return to Erbil in northern Iraq.

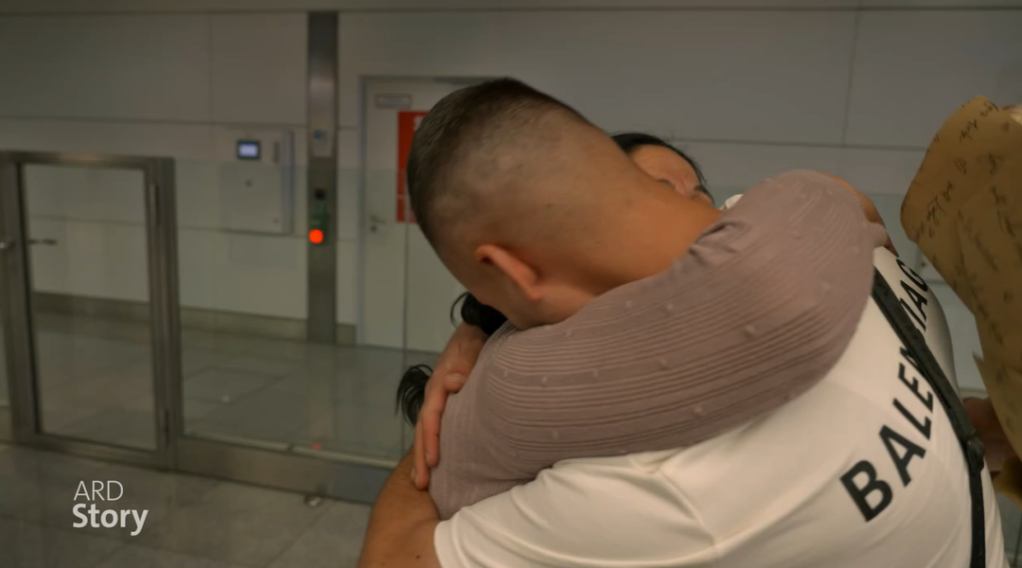

His tearful departure at the airport begins the documentary, as it follows his boss, Oliver Wendel’s attempts to bring him back to Germany.

"When someone has been working full-time for the last three years, pays his taxes, speaks good German, when we don’t keep these kinds of people, which types of people should we keep?" comments Wendel at the airport. Ashti had been working for Wendel since July 2023.

"At the time, he had a Duldung that was valid until May 2024, [a suspension of a notice to quit, often because it is not possible to send you back, because perhaps you don’t have the right documents, or your country is not safe.] That meant he was able to start work with us, and he just developed so quickly. He is really one of my best waiters," explains Wendel.

Seeing potential, Wendel asked Ashti if he would like to train as a qualified restaurant employee. Ashti was keen to start, and so Wendel began the application process. "It was mid-October and he came crying to us in the office. He was told he would have to leave on November 2. This really hit us hard," remembers Wendel.

Ashti was the only one in his family who was asked to leave, explains ARD. Until the beginning of 2023, there was a block on sending Yazidis back to their homelands because of the danger posed there for them by groups such as so-called Islamic State (IS) But that changed at the beginning of the year Ashti was asked to leave.

Read AlsoDo immigrants have to learn German in Germany?

Laws to attract migrants from abroad

In 2019, Germany passed a migrant labor law to attract migrants from abroad. Professor Herbert Brücker from the Berlin Institute for Empirical Integration and Migration Research explains that in 2019, Germany brought in 64,000 via this law. But that was before the pandemic.

"To keep things stable, we will need each year around 1.6 million people to enter Germany," estimates Professor Brücker.

To make that easier, the German government created a speedier process to bring some of those people in. On the website of Germany's asylum office, the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF), the accelerated procedure for skilled workers states it is designed to "help companies and skilled workers from third countries to reduce the time required for the entry procedure."

An employer can initiate the procedure, with agreement from the potential employee if there is a "concrete job offer" in question. The procedure is meant to "accelerate the recognition of foreign qualifications too."

There are seven steps in the process. However, in the examples highlighted in the documentary, most of the applications got stuck at stage three, the recognition of foreign qualifications, and took months or even years to move anywhere past it.

According to the documentary, the process up until stage three should take two months. If stage four should also be decided within two months, stage five in a week, and stage seven within six weeks, then the whole process, when it works properly, should take about six months.

Still waiting

In practice, some people are having very different experiences. Mikko Bayer told ARD, "it all looked good. We uploaded the documents requested, all seemed fine, four months passed and nothing happened." Bayer added that after four months, when he tried to contact the offices responsible in North Rhine Westphalia (the state in which he resides), "I just couldn’t reach anyone to talk to."

Frustrated at the process, the Bayers decided to write a letter to the state president Hendrik Wüst and threaten a legal process. Then suddenly they heard from the authorities.

"I then received a letter asking me to upload four contracts again. I thought I had uploaded all that in August, but no, they were asking for four new forms for a new office which recognizes people’s qualifications, the IHK Fosa," explains Mikko Bayer.

Read Also

Germany's migration policy: Balancing labor needs and deportation

'Bringing transparency to foreign qualifications'

The IHK Fosa in Nuremberg is responsible for recognizing qualifications and training for foreign workers trying to make it in Germany. Its director Heike Klembt-Kriegel states: "We are here to try and bring transparency to foreign qualifications. We then find a German training certificate that is equivalent to that and then, if we find it is equivalent, we can issue an equivalency certificate."

According to ARD, 50 people work at the offices in Nuremberg, and they are responsible for assessing people’s qualifications and training in 350 different professions and jobs. Only those who have a real equivalency to the level of German training expected are allowed to enter Germany.

Klembt-Kriegel says their work helps employers who might not be able to decipher foreign qualifications and training certificates alone. But the restauranteurs say that they weren’t worried about their applicants' training, they just wanted to bring them fast and legally to Germany.

'Absurd'

For Ashti, being back in Erbil, a long way from his family, is hard.

"This is not my country, I don’t know anything about how to function here," he says in fluent German. Wendel, who calls him most weeks, asks him what he does all day? "Nothing much," responds Ashti. "I spend most days at home, I don’t go out very much. I am just hoping that the visa comes soon. In the meantime, I try and watch German films on YouTube, to keep my German up."

"Ashti Sahlam Abdi’s case, was for me from the very beginning just so absurd, that I felt I had to help," explains Wendel. After consulting lawyers, Wendel decided that the only way to get Ashti back to Germany was via the accelerated skilled migrant labor process, and applying for a training visa for him to complete the training he had already begun.

Before he left, Ashti even took a German test to prove that he had the required level of German (B1 level). "Finally, eight weeks later, he got the results that he had passed. We thought at that point, that it would be a case of waiting two, maybe three weeks, until his visa was granted," explains Wendel.

"If it had gone like that, then I would have said that was a really good, and speedy, process," smiles Wendel. In March 2024, Wendel was still waiting.

Read AlsoVideo: Finland's hunt for skilled labor

Requests for more and more documents

The migration lawyer Anna Frölich tried to help Lemke with his fight to get the right papers for Russian chef Denis Shershnev, who was by this time living and working in Armenia while waiting to take up his post in Germany.

Despite Shershnev providing as many documents as possible, including job references and a timetable, some records from his training over 20 years ago were not available.

As a refugee, Shershnev didn't have access to that kind of documentation anymore, explained Frölich. The school where he trained and provided photos from had shut in 2015.

They told the authorities, that it was not possible to provide the exact timetable, but they sent in his references from most of the jobs where he had worked in the intervening 22 years.

After three months, Frölich was told that Shreshnev couldn’t be considered for the accelerated process. "I felt like they could have told us that sooner," comments Frölich. "They told us this was a complex case and that we would need to go down a different route."

Tax records and pension payments from abroad

That route, explains ARD, was via the IHK Fosa again. According to the Bayers, the IHK Fosa, when asked to check the equivalencies of the four Indonesian applicants, began asking for the tax records of the workers in Indonesian restaurants from the last three years.

"You have to realize," explains Mikko Bayer in the documentary, "most of those who work in restaurants in Indonesia don’t even earn enough to start paying tax. They started asking us to prove they had been paying into their pensions. Again, almost no one in Indonesia even has a regular pension, apart from maybe civil servants," said Bayer with raised eyebrows.

Every job and experience they had had, the documentary makers report, the IHK Fosa asked for documents proving that. Social security cards, references, visas. Klembt-Kriegel told the documentary: "Sometimes we have to ask for more documents because we have our doubts over the truth of documents that have already been sent to us, maybe something doesn’t add up."

Klembt-Kriegel insists that in the case of the four Indonesian applicants, they stuck completely to the correct processes and within the time they had promised it should take.

Read AlsoGermany recognizing more foreign qualifications

Could Germany be left behind?

Professor Brücker fears that Germany risks being left behind by other European countries, which are also looking for workers to boost their economies, and make it comparatively much easier for those people to start work.

"In Scandinavia for example, they look very generally at what kinds of qualifications and training someone might have, and they make these checks within three to five working days," claims Brücker.

After more than a year, Frölich received an explanation from the IHK Fosa that they couldn’t recognize Shershnev’s qualifications because they couldn’t prove that he had done a long enough training course, equivalent to the same kind of chef’s training in Germany.

When told the results, Lemke appears stunned. "(t)his person has been working for at least ... ten years at a very high level as a chef. He’s held down important positions in various kitchens. And then the whole thing falls down because they can’t prove that he did, I don’t know, five extra hours during his training?"

Lemke shakes his head. "And we are just sitting here, we don’t have enough chefs and we have been waiting for around one and a half years that he can start work with us. It really makes you think!"

Experienced worker visa

For those who really want the person to be employed, sometimes, new ways around these problems need to be found. Frölich hopes she might have found a way for Shershnev. She and Lemke begin applying for an experienced worker visa, via a different authority in Bonn.

At this office, applicants need to be able to prove they have completed a course that is officially recognized in their country of origin and also prove at least two years’ experience in their chosen field, completed in the last five years.

However, even with this process, the hurdles are set high. Applicants need to have a job offer where they will be earning at least 40,770 euros a year, although there are some exceptions. In the restaurant branch, explains ARD, a chef in Munich can usually expect to earn quite a lot less than this visa route requires. Most chefs in that city receive on average around 2,751 euros a month, but to qualify for this visa route, the chef would need 3,400 euros a month gross.

"I would be ready, for a well-qualified worker to pay that 3,400 euros a month, yes," says Lemke. "I gave Denis my word that he could work with us, so we will make sure we fulfill our side of the bargain if he can fulfill his."

Professor Brücker, who was one of the consultants for Germany’s social and labor ministry when they were designing the new labor migration laws, believes that in Germany the laws are made "in a climate of anxiety and fear."

Brücker thinks: "The laws are written up by legal experts who always start with very extreme cases of what might happen in a worst-case scenario. And of course, sometimes things do go wrong. There will be people who come here, and then need welfare and social help and will be a drain on our resources. That is really the big fear behind all these careful laws. But for us, who make economic-based decisions, and we see just how much economically we will lose if these people don’t come. These losses are much much greater than when, in a few cases, someone might need more social help from the system."

Read AlsoUnrealized potential: The challenge of 'brain waste' among Europe's skilled migrants

Partial success

It seems persistence pays. After five months away, Ashti receives his training visa in Erbil and flies back to Germany. He is able to begin his training at Wendel’s establishment, and hugs follow at the airport as he steps off the plane from Erbil.

In Cologne, after 11 months of waiting, two out of the four Indonesian chefs receive a recognition of their qualifications. However, by the time the program was aired, only one of them had actually traveled to Germany, reports ARD. The other two are wondering whether it is worth starting another visa process, or maybe whether they should apply in other countries.

In July 2024, Shershnev and Lemke applied for the experienced worker visa, but three months later, he had heard nothing. Finally, in October, the Bonn authorities responsible for carrying out this process wrote to Shershnev saying that his training in Russia had been recognized, and he could apply for the experienced work visa. The process is still under way when the film was broadcast.