Alaji is a 32-year-old migrant from Senegal. Eight years ago, he was convicted of smuggling migrants and causing death. He served his sentence, but maintains his innocence. With the help of the organization Baobab Experience, he wants to overturn his conviction.

Alaji is a 32-year-old man from a large, poor family in Senegal. He was in his early 20s when he arrived by boat in Italy. His mother tongue is Mandinga and, unlike many of the more educated Senegalese, Alaji is unable to speak French or Arabic.

Upon his arrival in Europe, Alaji couldn't read or write. Like many before him, Alaji left Senegal hoping to earn money in Europe to help support his mother and many siblings. His father wasn’t present when he was growing up.

Also read: Perpetrators or victims? Are the wrong people imprisoned in Italy?

Perhaps he was just unlucky, or perhaps he was an 'easy' target, since he couldn’t understand many others on the boat or in Italy. But when Alaji arrived, the testimony of one migrant landed him in jail. For seven years, he served a sentence on charges of migrant smuggling and causing death. Even after his release, Alaji maintains his innocence.

Several died on board the boat

The boat Alaji had been traveling on, explains Alice Basiglini from the Italian organization Baobab Experience, broke up during the journey. The planks along the hull of the boat snapped and several people suffocated as a result.

On average, about one in every 300 migrants is convicted of similar crimes to those Alaji is accused of, says Basiglini. When his trial went to court in Taranto, Alaji and a Gambian man were convicted of seven years in prison.

Also read: Burden of migrant management falls on police forces

Alaji though maintains his innocence, and Basiglini and the team at Baobab Experience say they believe him.

Basiglini explains why: "The one witness in the case that accused him of having piloted the boat was actually on another boat traveling some way off...It was also nighttime when they were traveling, so apart from the distance between the two boats, it would have been impossible to see who was actually piloting the boat."

'Fake smugglers'

The problem of "fake smugglers," -- people convicted on charges of smuggling even though they had no real connection to the organized criminal gangs that profit from people’s journeys -- is not uncommon in Italy.

Like many other European countries, the Italian state has promised to crack down on smuggling. Responsibility for prosecuting these people has been handed to the anti-mafia division within the Italian prosecution system.

"That means practically, that they apply the way they fight the mafia to the problem of migration, but that is not the same thing at all," explains Basiglini.

Also read: Migrants as smugglers, Europe's criminalization of those on the move

In Italy, the anti-mafia division seeks to dismantle criminal organizations by starting with the smallest players, who, they hope, will lead them to the biggest fish.

With migration, they believe that if they prosecute those who are accused of piloting boats, they will be able to put an end to smuggling schemes in the same fashion.

"But in fact those who may or may not be piloting boats have nothing or very little to do with the actual organizations that smuggle these people across the sea," says Basiglini.

A miscarriage of justice?

Even when people have been steering a boat, it is often either because they had less money than the others and were offered a cheaper trip if they agreed to act as the boat's driver. At other times, individuals end up steering because they already had some kind of seafaring experience.

Those from coastal states like Senegal and Gambia, who tend to have some knowledge of the sea, swimming or boats, figure heavily in prosecutions -- potentially for this reason.

But they, like the rest of those on board, are trying to get to Italy in one trip and don’t tend to make repeated trips working as a pilot.

Also read: A harrowing journey from Senegal to Europe

In Alaji’s case, says Basiglini, he and the other man convicted were sat near the fuel source but both of them deny ever having taken the tiller.

Basiglini says Alaji’s inexperience and lack of education may have counted against him. He was unable to understand the trial that he was subjected to, which she says was conducted in French and Arabic with no provision of a translation into Mandinga.

"He has, and still is, finding it hard to fully understand and process what happened to him," says Basiglini.

Conviction based on the testimony of one person, not on board

The conviction was based on the testimony of a single person, Basiglini says.

That witness had recently lost two of their sisters, one of whom died on the boat Alaji was traveling on, "so they had had a tough time psychologically," says Basiglini.

After completing his sentence last year, Alaji was released from a Sardinian prison and turned up in Rome "very confused, very upset, very vulnerable," says Basiglini.

Also read: Hero or villain? The 'smugglers' story

"Alaji tried twice to take his own life while in prison," says Basiglini. He once tried to hang himself and was saved only by his cellmate, the Gambian migrant --Bakary-- accused alongside him of piloting a second boat which arrived in Italy the same day.

"The other man had a higher level of education, he came from a more elevated social class and could understand the trial more easily," explains Basiglini. The two men are still in touch today.

'Italian prisons are not really about re-education'

On release from prison, Basiglini says Alaji was issued with a notice to leave the country. "But Italy doesn’t have a returns agreement with Senegal," so Alaji was cast into a society he’d never been able to get to know, except from inside the walls of his prison cell.

"Italian prisons are not really about re-education," says Basiglini, "they are really just punitive."

Despite being "completely lost and broken by his experiences," Alaji has shown a "strong sense of justice" since his release, Basiglini said.

Basiglini and her colleagues helped Alaji obtain a work permit, allowing him to start work as a gardener.

"He is very talented," says Basiglini. "Today Alaji has a permanent work contract, he is able to support himself and live independently. We hope that when his hearing comes up for special protection in June, he will be granted it."

Seeking information to overturn the conviction

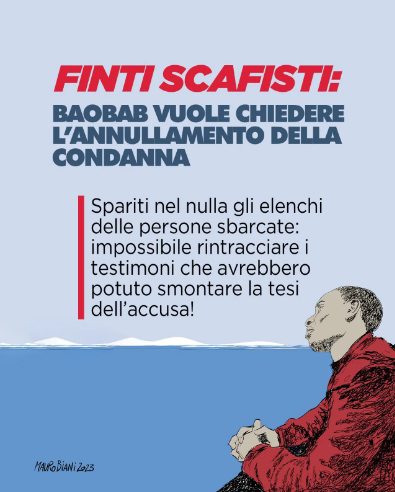

Since Alaji’s exit from prison, Basiglini and her colleagues have been trying to obtain more information about the man's case and trial in an effort to overturn his conviction.

"This would be a first in Italy if we manage it," says Basiglini.

First, in July 2023, a defense lawyer engaged by Baobab asked the prosecutor, under a freedom of information request, for a list of all those who arrived on October 20, 2015, the same day as Alaji.

They were hoping to build up a case for Alaji’s defense.

At the end of July, they received a first response from the prefecture in Taranto, explaining they believed the request was "inefficient" since nearly eight years had passed between the boat journey and the request.

When pushed, the prefecture said they had to check with the privacy guarantor, since there was a balance that needed to be struck between access to the information and people’s privacy, Baobab said.

Right to privacy vs right to a defense

According to Baobab Experience, the right to privacy should never outweigh the right to a competent defense, something they believe Alaji did not receive at his trial.

He was assigned a state defender who didn’t interrogate any other witnesses or even question whether the witness who accused Alaji could really be considered reliable, since they appear to have been traveling on a different boat.

In January 2024, Baobab’s defense lawyer received a response from the prefecture in Taranto.

"After repeated searches in the archives of this prefecture, we can’t find any documents relevant to this case, or any migrant arrivals on the date of October 20, 2015," the prefecture wrote to Baobab Experience.

In a press release responding to the answer, Baobab wrote: "Lists of people who could have provided witness statements [to help Alaji overturn his conviction] appear to have disappeared into thin air."

Vow to keep fighting for justice

Basiglini says they were "shocked" after receiving the response in January.

However, she said, the organization will keep fighting. First they want to overturn the case in Italy. Then they hope to take it to the EU level, to try and make an example out of this kind of problem.

As for Alaji, Basiglini says she believes he is "happier now than when he was in prison, but ... I don’t think he could be described as 'happy'."

Despite what happened to him, he is a very strong and structured person, she said, with a strong sense of justice.

"The Italian state stole seven years from him. He will never get that time back," she explains. "The least we can do is try to overturn his conviction."

"He was devoted to his mother, and when he was in prison, tens of thousands of kilometers away from her, with no way of contacting her, she died," says Basiglini. "That has had, and still is having, a huge effect on him, as he came here to Europe in order to support her."

Today, Alaji, with the help of Baobab Experience, is slowly learning Italian and to read and write. "But he had to start from nothing," says Basiglini.

Alaji will speak to InfoMigrants via an interpreter in the next few weeks to share more about his story and experiences. Watch our page for updates.