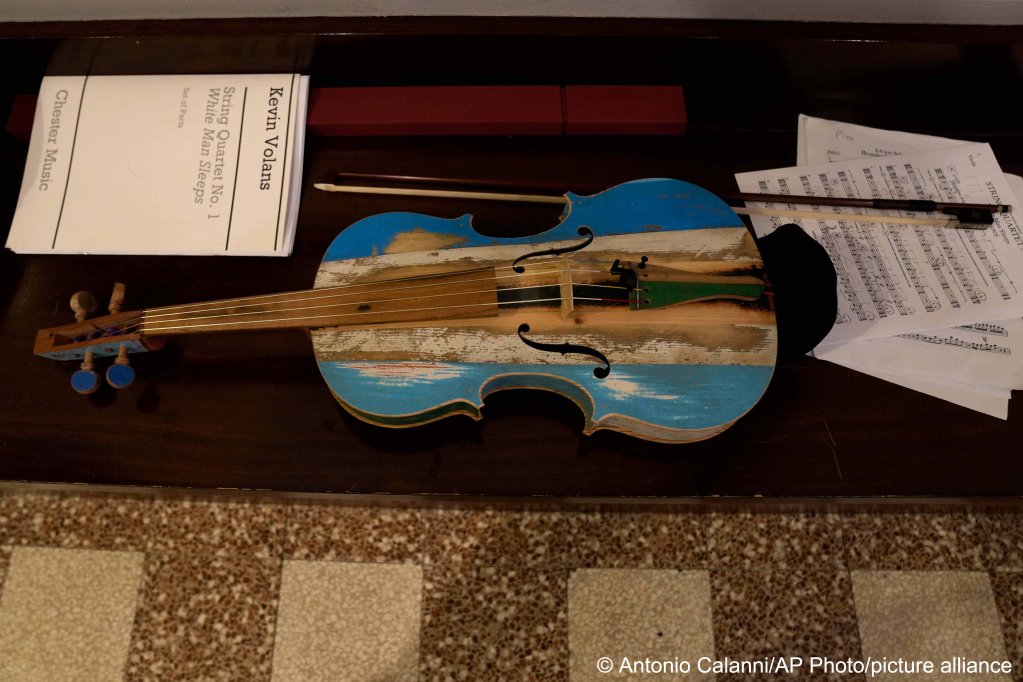

A project in Italy teaches prison inmates to handcraft string instruments from the remains of migrant boats. Now some of these are making their debut at Milan's famous Teatro alla Scala.

The violins, violas and cellos played by the "Orchestra of the Sea" in its debut performance at Milan's famed Teatro alla Scala carry with them stories of people on the move.

The wood has been bent, chiseled and gouged to carefully shape the instruments since it was recovered from dilapidated boats that brought migrants to Italy's shores, and those who created them are inmates in Italy's largest prison.

Also read: Maestros rrived in Italy by boat, now he makes his debut as a songwriter

A decade ago, the House of the Spirit and Arts Foundation first brought workshops for making stringed instruments to four Italian prisons.

Metamorphosis

The project, dubbed Metamorphosis, seeks to transform what otherwise might be discarded into a functional object valued by society. It gives new life to old wood while transforming inmates into craftsmen, all under the principle of rehabilitation.

Two inmates were granted leave to see the Orchestra of the Sea's debut concert Monday featuring 14 prison-made stringed instruments playing a program that included works by Bach and Vivaldi. They sat in the royal box alongside Milan Mayor Giuseppe Sala.

"I feel like Cinderella," said Claudio Lamponi, as a friend approached in the lobby before the show with a bow-tie to complement his new suit. "This morning I woke up in an ugly, dark place. Now I am here."

From inmate to master craftsman

The Opera prison on Milan's southern edge has over 1,400 inmates, including 101 mafiosi held under a strict regime of near-total isolation.

However inmates, like Nikolae, who joined Lamponi at La Scala, are permitted more freedom. Since joining the prison's instrument workshop in 2020, Nikolae has become Opera's master craftsman, graduating from crude instruments made out of plywood to violins worthy of La Scala's stage.

"That's how I began to speak with the wood," Nikolae said recently in the prison workshop, which is filled with the smell of wood chips amid the rows of chisels and the faint hum of a jigsaw. "I started with very poor materials, and they saw I had good dexterity."

Working on the instruments four to five hours a day gives him a sense of tranquility, he said, to reflect on "the mistakes I made" and skills that allow him to consider a future. "I am gaining self-esteem,'' he said, "which is no small thing."

One "graduate" of the prison workshops has completed his sentence and is now working as a master luthier (a craftsperson who builds string instruments) at another prison, in Rome.

"I hope one day, I can be recuperated, like this violin,'' Nikolae said.

Finding new purpose

Another prisoner, who preferred to remain anonymous, told AP that making the instruments is a form of therapy, physically and psychologically. He lived through two wars in his home country, which he also asked not to be identified because he served time as a political prisoner there and says he was beaten to the point of needing a crutch to walk.

He gently chisels the back of a violin's front piece, measuring the thickness with an instrument to achieve perfect pitch. His own journey to a new country helps him to identify with the people that fled on these unseaworthy boats.

"As I am working on these pieces, I think of the refugees that this wood transported, the women and children," he said. "I think only of that as I work, what this piece of wood has lived."

Lamponi and fellow inmate Andrea Volonghi have found a new purpose in their life sentences, pulling apart the old boats deposited in a yard among the prison blocks.

Transforming boats into instruments

Initially, the boats were being transformed into crucifixes and nativity scenes, but the inmates who had already been trained as luthiers thought: why not make instruments?

Also read: Chris Obehi, two places to call home

Now the prime pieces of wood are kept for the instrument workshop, removing rusted nails in the process. The more damaged wood is sent to another prison in Rome, where prisoners make crucifixes for rosaries -- the rosaries are then assembled by migrants at a Vatican workshop coming full circle.

When the boats arrive at the Opera prison they often still contain remnants of the migrants' lives, and with them a reminder of the 22,870 people who have died or gone missing on the perilous central Mediterranean crossing since 2014 according to UN figures.

"We don't know what happened to them, but we hope they survived,'' Volonghi said, looking at a tiny pink and white sneaker with a well-known logo.

Music from the sea

Each instrument takes 400 hours to create, from disassembling the boats to the finished product. While a classic violin made in the workshops of Cremona, an hour's drive from Milan, will use fir and maple, the instruments of the sea are assembled from a softer African fir, the sun- and sea-drenched hues of blue, orange and red left as a reminder of the wood's past life.

"These instruments, which have crossed the sea, have a sweetness that you could not imagine,'' said cellist Mario Brunello, a member of the Orchestra of the Sea. "They don't have a story to tell. They have hope, a future."

Also read: Healing through music, London choir changes perceptions about migrants

The House of the Spirit and Arts Foundation, which runs the workshops, hopes the concert at La Scala will be the start of many performances by Orchestra of the Sea all across Europe.

"The beauty is that music overcomes all divisions, all ideologies, goes to the heart and soul of people, and one hopes that it makes people think," said foundation president Arnoldo Mosca Mondadori.

"Politicians need to think of this drama."

This article was based on a feature from Associated Press (AP) written by Colleen Barry