Last month, Niger’s military government repealed an anti-migrant smuggling law. Analysts say that it disrupts the European Union’s move to outsource migration control policies to African nations and signals the continued souring of diplomatic relations with Europe.

Niger’s military government repealed a controversial anti-migrant smuggling law last month and expunged earlier convictions handed out as a result of it, news agency Al Jazeera reported in late November.

The anti-migrant smuggling law criminalized the transport of migrants from the north-central Niger town of Agadez to Libya and Algeria -- two common starting points for African migrants looking to reach Europe.

The revocation of the 2015 law, which was implemented with the support of the EU through the €5 billion EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, is the latest rupture in the already constrained diplomatic relations between Niger and the bloc.

"By revoking the 2015 law, the military junta reiterates the end of the cooperation with the EU, including on migration matters, which was crucial to the EU's migration strategy," Alia Fakhry, associate researcher at the German Council for Foreign Relations (GCFR), told InfoMigrants.

Between 2014 and 2020, more than one billion euros of the Emergency Trust Fund for Africa went to Niger.

Read more: How the EU spent billions to halt migration from Africa

Migrant smuggling "state-sanctioned"

While the repeal of the law reportedly worried Brussels, who feared that it would further fuel irregular migration to Europe, locals reportedly rejoiced over migrant smugglers no longer being considered criminals in Niger.

"It’s a law that contravened the free movement of people and goods, so it was very well received … if we see migrants, we will transport them,” Sidi Mamadou, 42, a former smuggler and activist for legal immigration, told France24.

Fakhry explained: "Smugglers were perceived as transporters who moved goods and people across borders. Military convoys accompanied smugglers’ convoys for security reasons, but the military also collected informal taxes from smugglers. In a way, migrant smuggling until 2015 was state-sanctioned. It was partly controlled by military actors and generated revenues."

The law was also heavily criticized for its negative consequences on people who benefited directly or indirectly from the presence of migrants in Niger.

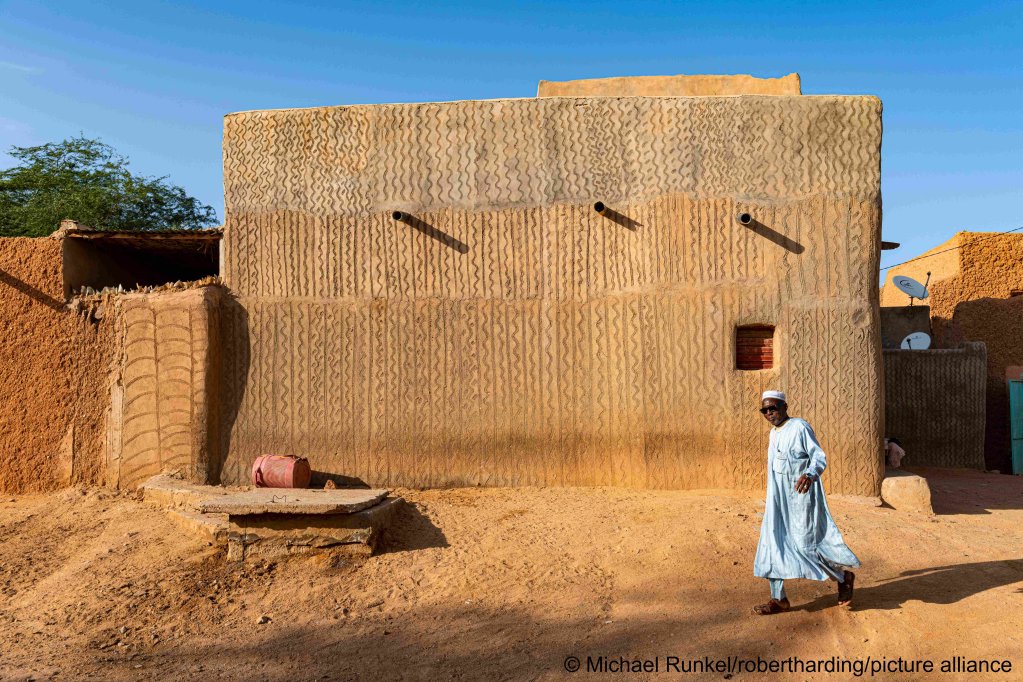

Agadez region was, until 2015, an important transit hub. It contained a mix of migrants, traders and seasonal workers who kept businesses along the route alive. With the implementation of the anti-migrant smuggling law, "smugglers but also shopkeepers, food sellers, and lodgers suddenly went out of a job," said Fakhry.

The move on the part of Niger’s military government now signals a possible return to the pre-2015 situation.

Narrowing pathways for legal and safe migration

"The (EU) obsession with immigration is well known,” Yéra Dembele, president of Paris-based migration think tank Fédération Euro-Africaine de Solidarité (FEASO) told InfoMigrants.

In recent decades, Europe has shifted away from its postwar migration policy aimed at attracting migrant labor badly needed to rebuild after World War II. In recent years, the bloc has taken to bolstering border controls on land and sea to keep out irregular migrants out.

According to Dembele, only one thing has remained unchanged.

"When we look at the evolution of flows during these different phases, we realize that tougher policies have had virtually no effect, apart from increasing the number of migrants drowned at sea,” said Dembele.

Dembele also criticized migration and development policies of places of origin such as Africa as aligned with the host countries "with no real political will to satisfy the needs that drive young people to emigrate at the risk of their lives.”

Also read: Niger: why the repeal of the anti-migrant smugglers law worries the European Union

Also read: Niger: the ruling junta repeals the law criminalizing migrant smuggling

EU’s externalized borders: from domino strategy to domino effect

Analysts say it is too early and too difficult to say how the unfolding situation in Niger will impact regional migration dynamics. However, according to Fakhry, the loss of the Niger partnership could push the EU to forge similar cooperations with other nearby African countries. The bloc has already finalized such deals with Tunisia and Libya.

"The EU continues to consolidate its migration strategy. The deal with Tunisia this summer is an illustration of what we can describe as a 'domino' strategy. With the Niger 'domino' falling, the EU looks to consolidate other partnerships,” said Fakhry.

"With the end of the cooperation with Niger, there is an important lesson to be drawn for Europeans: by pursuing a migration strategy that overly relies on the cooperation with good willing partners, Europeans fall prey to mood swings and regime changes,” she added.

The unrest in the Sahel

Since 2020, seven coups have taken place across Africa, five of which occurred in countries located in the Sahel region: Niger, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Chad and Mali.

The most recent was the military takeover in Niger last July.

The military takeovers are related to the political insecurity, poverty and violent extremism that have plagued the Sahel and driven what the Institute for Security Studies has called an immediate effect of "forced and voluntary migration from the region to other parts of Africa towards Europe”.

Data from European border management agency Frontex indicate that this year saw the biggest rise in the number of irregular crossings along the Western African route, which connects Western African countries and the Canary Islands in Spain.

The estimated 27,700 irregular arrivals this year is the highest number recorded along the Western African route since 2009 when Frontex began tracking arrivals.

In October alone, Frontex noted 13,000 arrivals, the highest monthly total on record of migrants who typically set sail for Europe from Morocco, Western Sahara, Mauritania, Senegal and the Gambia -- areas that are either connected to or part of the Sahel.

A common knee-jerk reaction from the EU and the UK is to create new forms of border control in countries of origin such as Africa.

Migration within Africa: inter-nation, not cross-border

However, experts and advocates say that migration interventions, which are mostly drafted from a European viewpoint of curbing migration, have fallen short and will continue to do so because they do not account for the nature of movement within Africa, which is influenced by both cultural and colonial history.

"When we hear migration, we think it is getting out of Africa to go to other places like Europe. But what is rarely talked about is how movement in Africa is mostly from moving from one neighboring African country to another -- which has been going on for centuries,” Makmid Kamara, a human rights campaigner and researcher, told Infomigrants.

"Borders were put in by colonial powers to divide the lands they conquered and, in that sense, artificial. For many Africans, it is not crossing borders when they move from one neighboring country to another,” Kamara explained.

"What we are seeing now more and more is how the recurring political instability is displacing people and transforming the routes used for economic movement to pathways to seek refuge,” said Kamara.

The United Nations High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR) estimate that about 3.7 million people have been internally displaced in the Sahel with more than half a million refugees and asylum seekers seeking protection in neighboring countries. The regions of Centre-Nord and Sahel in Burkina Faso host the largest internally displaced populations and the highest levels of food insecurity.

Need for African-centered development interventions

In addition to the political instability, the impact of the climate crisis also disproportionately affects the central Sahel region, where temperature increases are 1.5 higher than the global average.

"The adverse effects of climate change and conflict are some of the leading drivers of mobility with others moving for economic reasons,” Kennedy Okoth, the communications officer for Europe, Africa and the Middle East for the International Organization for Migration (IOM) told InfoMigrants.

According to the International Rescue Committee (IRC), the countries in the Central Sahel account for 5% of global humanitarian needs but only make up 0.9% of the global population.

High youth unemployment further adds to the restlessness -- and the motivation to move. The UN estimates that around 64% of the population in the Sahel is under the age of 25.

"These young people long for a future. What we need are development policies that can give them that. We can write pages and pages of migration protocols, but until we have real development interventions -- from both Africa and the European Union -- people will continue to move. The political instability will just make them more desperate to do so,” Kamara concluded.