After rescuing around 300 migrants in the central Mediterranean, Geo Barents is still cruising towards La Spezia in the north of Italy. This has prompted charities, once again, to criticize Italy’s policy of assigning ports of safety sometimes 1,000 kilometers away from the rescue site.

The Geo Barents private rescue ship, operated by the medical humanitarian charity Doctors without Borders (MSF), is currently sailing towards the port of La Spezia on Italy’s north-western coast. It is one of Italy’s most northern ports, and over 1,000 kilometers and several days sailing away from the site in the central Mediterranean where the Geo Barents rescued 336 migrants on May 1.

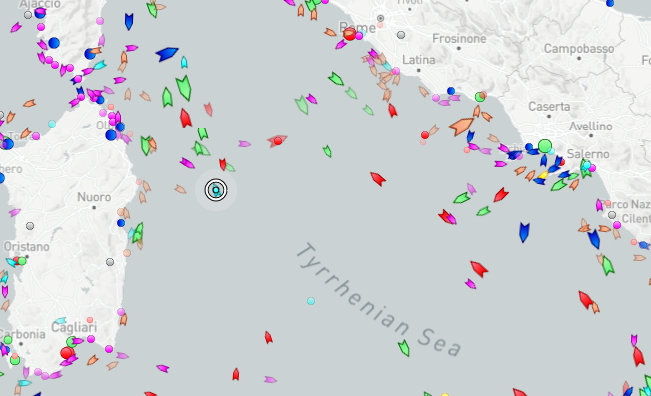

At the time of writing, the ship is sailing between the Sardinian coast and a little way south of Rome on the Italian mainland. Its expected time of arrival according to the website Marine Traffic is May 5 at midday.

Life Support, the rescue ship operated by the Italian medical humanitarian charity EMERGENCY also complained this week about long sailing times after being assigned the port of Livorno, on the Tuscan coast in central Italy. The ship disembarked the 35 migrants it rescued on April 29 in Livorno on May 3.

Long sailing times before disembarkation

These long sailing times has prompted MSF and several other private rescue charities to denounce, once again, Italian policy and ask why they can’t be assigned a port nearer to where they picked up migrants.

In a post on their Twitter feed, MSF says that La Spezia is around 1245 kilometers, or 672 nautical miles from where they carried out the rescue. "A place of safety should be assigned with minimum deviation from the ship’s voyage," states MSF.

In fact, according to MSF records, the rescue of the 336 migrants took place in the Maltese search and rescue zone (SAR) and included "many women and children." When assigned the Port of La Spezia on May 2, MSF asked why they couldn’t have been directed to the ports of Pozzalo, Palermo or Augusta on the island of Sicily.

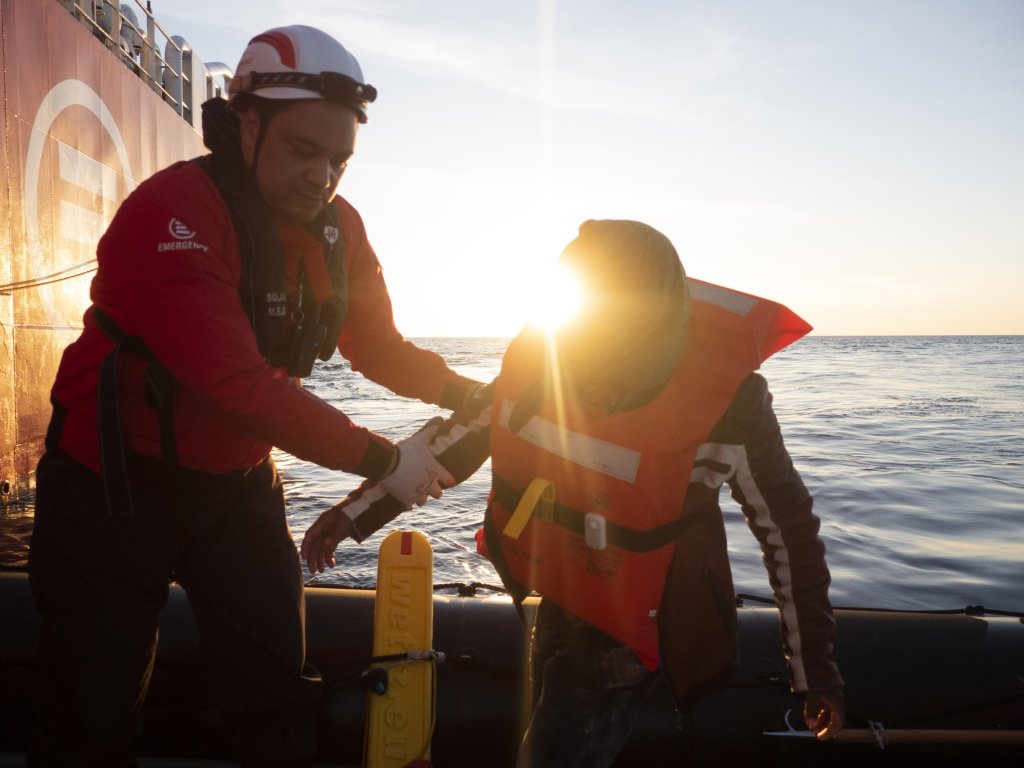

MSF says that the long sailing times in between rescue and disembarkation also “affects the physical and psychological well-being of survivors. After their traumatic experience, this unecessary waiting causes them even more suffering,” states the charity.

EMERGENCY explained in a press release on May 3 that the group of migrants it rescued had already been at sea for four days when they found them off eastern Libya. A further five days was needed before they could safely disembark, stated the charity.

'He thought he would not make it'

One of the cultural mediators on board, Ahmed Echi, commented in the press release about the state of one of the young men the group rescued. "I was very moved by a young man who, after the rescue, was shaking and in a state of shock: after almost four days of sailing on the overcrowded and precarious vessel they had left on, he thought he would not make it. But in the four days of navigation it took to get from the rescue site to the port of disembarkation, we saw the people on board start to get better."

The European Council on Refugees and Exiles ECRE have also criticized Italy’s policy. In a tweet on their page from May 2, ECRE calls Italy’s policy of assigning ports far away "illegitimate" and claims it is being done deliberately to "obstruct the work of search and rescue NGOs and re-traumatise and exhaust already exhausted and traumatised people."

International law of the sea

ECRE says Italy should have "some respect for international law and some compassion for people on the move."

Although both ECRE and MSF imply that Italy might be going against international law, the International Institute for Law of the Sea Studies ILSS, states that "ports are under the territorial sovereignty of the coastal state." It continues that that state "may regulate foreign vessel’s entry to its ports."

The ILSS goes on to say that the "coastal state is empowered to establish particular requirements for the entry of foreign vessels into their ports…," although admittedly this is to prevent pollution in the case of warships or nuclear-powered ships or those carrying noxious substances.

In terms of merchant ships, reciprocal treaties of friendship and commerce as well as the Geneva Convention and the International Regime of Maritime Ports, "every contracting state undertakes to grant the vessels of every other contracting state equality of treatment with its own vessels, or those of any other states whatsoever, in the maritime ports situated under its sovreignty or authority, as regards freedom of access to the port, the use of the port, and the full enjoyment of the benefits as regards navigation, and commercial operations which it affords to vessels, their cargoes and passengers."

The paragraph concludes that "[i]t can be presumed that normally the ports of the coastal state are open to merchant vessels unless otherwise provided."

Sea-Watch: 'New decree...is a call to let people' drown'

Italy’s government has mostly refused to comment directly on the assignation of ports, but when it has been criticized in the past, it has often cited logistics as one reason why it has assigned ports further away from the ones most usually used for disembarkation on the island of Sicily. Overcrowding in reception centers on Sicily and Lampedusa, as well as stretched resources in an already poorer part of Italy could also influence their decision.

The German-based private rescue charity Sea-Watch has also criticized Italy’s new policy, announced in a decree passed at the end of December 2022. In a press release at the time, they said the Italian government was "explicity assigning distant locations as safe ports for disembarking rescued persons," in order to keep "rescue ships...away from the rescue zone for as long as possible."

A spokesperson for Sea-Watch, Oliver Kulikowski, commenting on another part of the decree which stipulates that as soon as a private rescue ship has carried out one rescue, they are expected to seek a safe port by which to disembark before embarking on further rescues, said "the Italian government’s new decree is a call to let people drown. Forcing ships into port violates the duty to rescue should there be more people in distress at sea."

The decree also asked civil rescue ships captains to obtain a declaration from rescued person on their willingness to apply for international protection. According to Sea-Watch, this lacks any legal basis. The UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR clarified that "ship captains are not responsible for determining the legal status of rescued persons."

Sea-Watch’s medical coordinator, Hendrike Förster, added that forcing ships to travel further before disembarkation essentially meant that the "Italian government thereby makes itself directly responsible for health consequences on board the rescue ships."

Arrivals in Italy

Although Italian policy has come under fire from migrant charities and human rights organizations, it doesn’t seem to have had much effect on the numbers of those arriving, the vast majority of whom are actually rescued by the Italian coast guard or border police, or arrive on the Italian coast under their own steam.

In figures from the Italian Interior Ministry, last updated on May 4, 42, 405 people have arrived in Italy by sea this year. The arrivals for every month since 2023 began have been significantly greater than the arrivals in the equivalent months in both 2022 and 2021. In April for instance, 14,512 people arrived in Italy in 2023, in April 2022 by comparison, 3,929 people were recorded as arriving and in April 2021 just 1,585.

According to Italian data, the majority of arrivals this year so far are those coming from Ivory Coast, followed by Guinean nationals, then Egyptians, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis and Tunisians in descending order. Nationals from Syria, Cameroon, Burkina Faso and Mali all account for more than 1,300 arrivals each, and almost a quarter of arrivals (9,245) do not feature as a distinct large-enough national group in the statistics, or perhaps their country of origin was unclear.

The UN Migration Agency IOM's Missing Persons project concluded that April 2023 was the deadliest month on record since 2018 for those going missing or dying in the central Mediterranean. In fact, 389 people died or were declared missing during the month.