The first group of migrants to be processed in Italy's divisive asylum centers built in Albania are due to arrive in the Balkan nation on Wednesday, October 16. The offshore processing scheme has attracted a lot of criticism but other EU countries watch with interest as to whether the scheme could work.

The group of 16 men were intercepted at the weekend by the Italian navy as they attempted to cross the central Mediterranean.

Ten men from Bangladesh and six from Egypt reportedly departed on two separate boats from around Tripoli in Libya, according to an anonymous Italian government source who spoke to the AFP news agency. The DPA news agency later also confirmed the nationalities of the migrants.

Even though they were technically intercepted on the open sea and in international waters, they were found within Italy's search-and-rescue zone, which means that Italy is in charge of processing them.

Their journey towards Italy's offshore processing facilities in Albania comes just days after they were declared open by the Italian authorities. Italy hopes that processing eligible migrants in the centers will speed up asylum assessment and allow for faster deportations if the asylum applications fail.

Interior Minister Matteo Piantedosi praised the scheme, saying that "everyone can apply for international protection [there] and receive a response in a few days."

Italy's far-right government struck the deal after a continuous rise in the number of migrant arrivals in the first year after it took office, 2022-2023. Italy is one of the EU states that receive the greatest number of people seeking to reach Europe by crossing the Mediterranean Sea.

Read AlsoWhat is the Italy-Albania deal on migration?

Italian law in Albania

The Albanian centers are initially set to run for five years, with Italy reportedly estimated to be intending to pay the Albanian government roughly 160 million euros a year to process would-be asylum seekers there.

In a bid to reduce the arrival numbers of irregular migrants to Italy, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni struck the deal last year with the Albanian government as a strategic partnership.

Although Albania is not an EU member state, Italy has been keen to point out that Italian jurisdiction applies within the centers and all processing will be done within the norms of EU and Italian law.

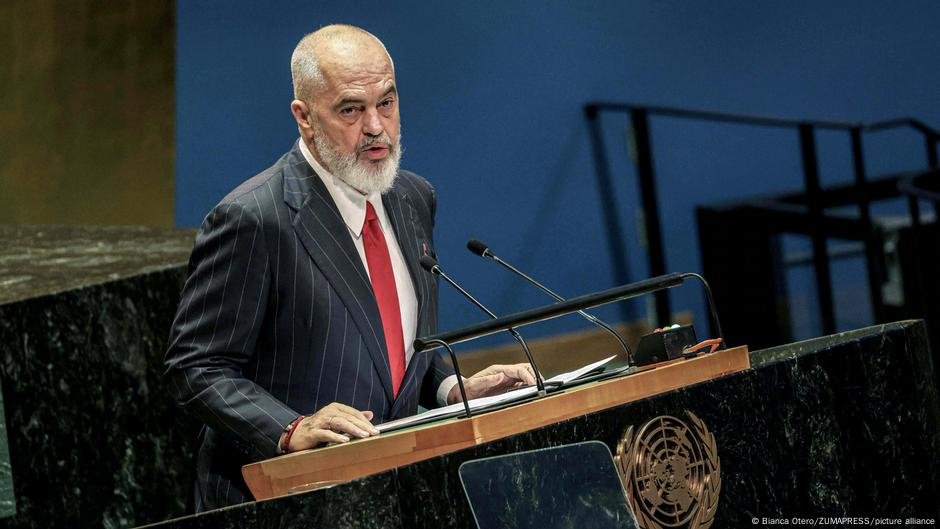

Currently, it is unclear if the deal could be extended, and under what circumstances. Just as Albania was getting ready to receive the first 16 migrants, Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama also officially announced that his country had taken the next step towards joining the European Union, with the first accession negotiating chapters opened on October 15 following ten years of waiting as a candidate country.

Across the Adriatic Sea

Under the agreement, non-vulnerable male migrants intercepted by the Italian navy or coastguard vessels in international waters — but within Italy's search and rescue area — could be sent to the Balkan country to have their chances for qualifying for asylum in Italy assessed there.

The exact procedure involved stipulates that migrants picked up at sea will first be brought to a camp at the Albanian port of Shengjin for initial checks, including health and welfare assessments.

They will then be transferred to the main camp in Gjader, which is where Italian authorities will examine the exact content of their asylum applications.

The centers will be operated under Italian law, with Italian security and staff inside and Albanian security on the outside. Judges will hear cases via video link from Italy to decide on cases, stated the Italian authorities.

Those who are deemed to qualify for asylum under Italian and EU law, will then travel to Italy from there. Those rejected will be deported back to their own country where possible.

Read Also'Migrant centers in Albania like prison camps' say Italian unions

Men only

The scheme clearly states that it particularly targets men who originate from countries that are deemed "safe."

Currently, there are 22 countries which according to Italian law are "safe": Albania, Algeria, Bangladesh, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Colombia, Gambia, Georgia, Ghana, Egypt, Ivory Coast, Kosovo, Nigeria, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Morocco, Peru, Senegal, Serbia, Sri Lanka, and Tunisia.

Women, children, people with illnesses and disabilities as well as people who are proven to have been subjected to torture will not be sent to Albania, according to the guidelines under which the centers say they will operate, even if they come from the aforementioned countries.

Minors, whether they are accompanied by a parent or caregiver or traveling alone, will also not be sent to Albania.

The Italian authorities eventually hope to process tens of thousands of migrants through the facilities every year. They claim the facilities can hold up to around 3,000 migrants at a time and say they will deal with claims within around 28 days of arrival.

Meloni's 'example'

The scheme has attracted a great deal of criticism since its inception but has also been praised by some experts on asylum who believe it might offer a route for other countries around Europe to manage migration.

Meloni herself has hailed the deal as "courageous," saying her government in Rome was setting a "good example" for other countries to follow. Meloni's influence within the European administration has increased following elections in June, when voters moved the parliament slightly more to the right. The Italian prime minister claims her new migration strategy "perfectly reflects the European spirit."

The scheme is being observed with interest in other European countries. Germany and the UK are among administrations to visit Italy to find out more about Meloni's migration strategy in the wake of her government announcing they had reduced the numbers of arrivals over the last year by 60 percent compared to the previous year.

However, these figures should be read with a caveat, since the numbers of arrivals to Italy in the first year of Meloni's administration almost doubled, meaning that the current arrival levels have returned more or less to the numbers arriving before her government took power.

The Italian example is expected to be discussed at an upcoming summit of EU leaders later this week.

Some analysts have sought to compare Italy's Albanian centers to the UK's previous plan of sending asylum seekers to Rwanda. However, the two differ in several ways, perhaps most importantly in that Britain did not intend to accept anyone whose asylum claim was recognized during the process.

After being challenged continually in court, the plan was abandoned by the incoming Labour government when Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer took office in July.

Read AlsoUK:The end of the Rwanda plan

Strong criticism of scheme

Human rights groups question whether migrants on Albanian soil can truly benefit from access to the same kind of treatment they otherwise would receive in Italy.

Amnesty International described the scheme as a "cruel experiment (that) is a stain on the Italian government."

Amnesty also said that the agreement "is highly unlikely to reach its stated aim in terms of migration management," stressing that "its implementation would have a negative impact on a range of human rights, including the rights to life and physical integrity of people in distress at sea, and the rights to liberty, to asylum, and to adequate remedy, of people transferred to Albania."

The NGO SOS Humanity, which operates a private rescue vessel in the Mediterranean Sea, went even further and said that "the agreement between Italy and Albania violates international maritime law and risks further undermining the fundamental rights of refugees."

"The agreement violates the international obligation to disembark survivors at the nearest place of safety. The Albanian port of Shengjin is around 1,000 kilometers away from the rescue area, which means several additional days of travel time compared to disembarking in [nearby Italian islands like] Lampedusa or Sicily."

Another sea rescue NGO — Sea Watch — meanwhile referred to the launch of the scheme simply as a "dark chapter."

UNHCR to monitor progress

Outside NGO circles, the Council of Europe has also raised concerns about the Italy-Albania deal. Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Dunja Mijatovic, stated that the development "adds to a worrying European trend towards the externalisation of asylum responsibilities."

Mijatovic stressed that the deal "creates an ad hoc extra-territorial asylum regime characterized by many legal ambiguities. In practice, the lack of legal certainty will likely undermine crucial human rights safeguards and accountability for violations, resulting in differential treatment between those whose asylum applications will be examined in Albania and those for whom this will happen in Italy."

In order to ensure due diligence at the Italian centers in Albania, the UNHCR will monitor proceedings there for the first three months of its operation after also expressing "serious concerns."

"At the end of the three-month period, UNHCR will make available its recommendations to the Italian government and other interested actors," the UN body stressed in a press release.

The UNHCR added that it was not a party to the Italy-Albania deal, nor was it consulted during its inception.

One former Head of Policy Development & Evaluation Service at the UNHCR, Jeff Crisp, now at the Refugee Studies Center at Oxford University, commented on X on Tuesday (October 15) that the facility "looks like an atrocious place to incarcerate refugees and asylum seekers."

with dpa, AFP