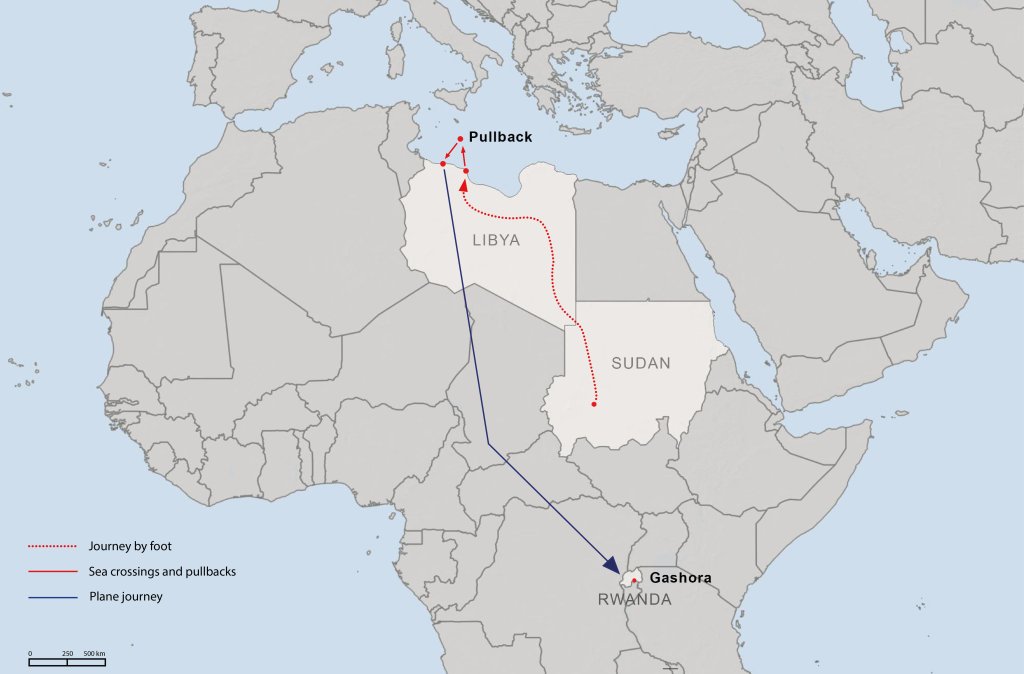

Irshad’s journey from Libya to Rwanda reflects the challenges faced by refugees awaiting resettlement. Transferred through a UNHCR program, he remains in the Gashora transit center, hoping for relocation to a third country. As European countries explore outsourcing asylum, Irshad's experience raises questions about Rwanda as a temporary location for refugees.

"Don’t worry, I'll find you," Irshad reassured us over the phone as we got out of the minivan on the main crossroad of Gashora, a small town 40 kilometers southeast of Kigali, Rwanda. He soon waved at us walking up the only asphalted road in town. "You are lucky to have come now when the road is built," he said. "It's a less bumpy ride."

Irshad is one of the 600 refugees in the Gashora transit center, set up by the UNHCR’s Emergency Transit Mechanism (ETM), an international pilot program to evacuate vulnerable refugees from Libya's detention centers.

The paving of the village's main road is one of the compensation payments agreed upon by the UN Refugee Agency and the Rwanda government as part of the local development package to host the center in one of the regions most affected by the genocide of 30 years ago.

Irshad walks us past the main gates of the center and into one of the one-storey cafes facing the road. We soon learn this is the only place in Gashora where the asylum seekers in the center feel comfortable to sit and hang out. Turquoise blue walls and straw chairs. Unlike the other bars on the newly built road, this doesn’t serve beer. "And the cook is Eritrean," smiles Irshad, hinting at the food tasting better than elsewhere in the small village.

Last July, the UK's newly elected Labour prime minister, Keir Starmer, shelved the controversial policy that threatened to transfer to Rwanda anyone arriving to the UK crossing the Channel on a small boat. The policy was judged unlawful by a UK court, deeming Rwanda unsafe for asylum seekers due to risks of unlawful refoulement to their home countries.

Despite the failure of the UK-Rwanda deal, outsourcing asylum to third countries is still being contemplated by many EU member states. Italy is building two migrant detention centers in Albania to process the asylum claims of people rescued at sea. Denmark has long been echoing the UK plan to offshore asylum to Rwanda, a proposal also gaining traction in Germany after the recent victory of the far-right in local elections.

In contrast, resettlement focuses on providing refugees with permanent protection in third countries. To better understand these dynamics, we traveled to Rwanda to speak with asylum seekers about their experiences with resettlement. This is how we met Irshad.

Read AlsoWhat is the Italy-Albania deal on migration?

Escaping Libya

Originally from Darfour, Irshad reached Libya in 2018 to cross the Mediterranean with his older brother. "We got separated once we tried to get on the boat. My brother managed to reach Italy at his first attempt," says Irshad, "but the boat I was on was stopped by the Libyan coast guard."

He tried crossing the sea another seven times, but never managed to cross. Pullbacks are a technique used by the Libyan coast guard to intercept boats and dinghies and take them back to Libya before they reach international waters, preventing asylum seekers from being rescued and reaching Europe.

Each return was followed by imprisonment in a Libyan detention center. "You only leave prison if you pay. If you can’t pay, they force you to work. You have to try and stay alive until someone pays for you or they let you go," he says, referring to the militias that run the prisons.

As we speak, more people join the conversation. Most of them are friends of Irshad from Eritrea, Somalia and Sudan: all met in Gashora. They take chairs from other rooms and sit around, wanting to join in the interview. Their testimonies of spending months in Libya echo Irshad’s story. Some show the scars they got from torture inflicted upon them in detention, shining marks on their arms, legs and backs.

The UN opened the ETM as an attempt to break the cycle of embarkations, pullbacks and imprisonment experienced by thousands of asylum seekers in Libya. "I agreed to the UN program because anything is better than being in Libya," says Irshad, explaining he was glad to be transferred to Rwanda in 2022. "But I didn’t know I would end up staying stuck here for years."

Stuck in Rwanda

As comforting as leaving the hell of Libya’s detention can be, temporary resettlement in Rwanda can turn into its own kind of prison. "Technically people shouldn’t stay in Rwanda for more than six months. Those who get referred to the ETM are the most vulnerable people in Libya and are very likely to be recognized as refugees and be eligible for resettlement to the US, Canada or Europe," says R.S., a program officer working for an international NGO referring people to the ETM in Libya.

However, leaving Rwanda for a safe third country ultimately depends on those countries accepting the refugee’s asylum applications. If the application is denied, for whatever reason, applicants have to start the process again making an asylum request to another country, a process that takes months.

R.S. agrees to speak to us anonymously. He knows how easily his words might be manipulated in describing the nuances of the ETM. "There is no question that being transferred to Rwanda is better than remaining in detention in Libya. But the ETM is not a solution. It is a way to try and address the specific dramatic situation in Libya. It is not a model that can be reproduced by European states wishing to outsource asylum somewhere else."

The ETM aims to tackle the emergency conditions of the most vulnerable people in Libya’s detention centers, providing a temporary safe location in Rwanda to resettle asylum seekers whilst a more permanent resettlement is arranged. But the Gashora transit center can only accommodate 600 people at a time. For refugees to be transferred from Libya, the ones already in Gashora have to first be resettled to other countries.

After arriving in Gashora, Irshad hoped leaving Rwanda was going to be just a matter of time. "I have friends who were accepted in France and in the US," he says. "My sister is in Toronto, and she got there through the ETM last year." A young Eritrean man sitting next to Irshad is bound to leave Gashora that very day, he explains. His asylum application has been accepted in France. "We don’t really know on what criteria our applications get accepted or refused. But as soon as people manage to leave Rwanda, then others arrive from Libya."

Irshad wasn’t as lucky. His application to reach his sister in Canada was refused a few months ago. He wasn’t given any reason why, nor a way to appeal the decision. "I have no idea why they refused my application. I will have to make another one somewhere else, and it might take years." There are asylum seekers who have been in Gashora since the ETM opened in 2019, he says. They keep on getting refused every time, and have no other option but wait and keep applying. "They live in limbo."

Read Also119 refugees evacuated from Libya reach Italy -- UNHCR

Transit mechanisms and outsourcing to third countries

Despite the failure of the UK-Rwanda deal, due to the presence of the ETM, many EU countries are looking at Rwanda as a desirable location to offshore asylum.

Kagame’s regime, under international scrutiny for the violent repression of political oppositions and freedom of the press, still managed to present Rwanda as a safe haven for refugees, capitalizing on Rwanda’s post-genocide reconciliation, unparalleled economic development in the region, and the presence of around 80,000 refugees from neighboring DR Congo and Burundi.

When the UNHCR provided evidence to UK courts of Rwanda’s asylum system being inadequate to host refugees, Kagame’s government responded by accusing UNHCR of hypocrisy, criticizing Rwanda abroad but partnering with Kigali to transfer refugees from Libya.

In May this year, the interior ministers of 15 EU member states signed a letter to Ylva Johansson, then EU Home Affairs Commissioner, describing the outsourcing of asylum to 'safe third countries’ as a solution to address irregular migration. They also cited "place of safety arrangements and transit mechanisms" like the Emergency Transit Mechanism as potential models for "durable solutions."

'The problem is having no certainty about your status'

This contrasts with the ETM's temporary nature in Rwanda, where asylum seekers are intended to stay only while awaiting permanent resettlement elsewhere. While Rwanda offers the option of permanent stay, none of the over 2,000 people who have passed through the program have chosen to remain.

"No one wants to stay in Rwanda," says Irshad, gesturing to the group of young men who have joined our conversation. "It's not because Rwanda is unsafe," he continues. "Rwanda is very safe if you don’t make trouble. The problem is having no certainty about your status and how long it will last. What guarantees do we have that we will not be sent back to Sudan?"

Another crucial issue is the lack of perspectives asylum seekers face in Rwanda. "There is no work for refugees in Rwanda. That's a fact," says Irshad.

Asylum seekers in the Gashora camp are not allowed to work, despite many still traveling to nearby towns and trying to round up the weekly allowance provided to them in the Gashora camp. "You know how much I get for a day of work in Kigali?" asks Irshad. "2,000 Rwandan Francs [about 1.5 US dollars]. A packet of cigarettes here costs 1,500 RF. How can you survive like this?" says Irshad.

"I am grateful I could leave Libya. But bringing refugees to Rwanda from Europe is a terrible idea. Local Rwandese are struggling with finding work. How does anyone expect refugees who don’t know the country, don’t speak the language and have survived Libya to do so?"

This article was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe

Read AlsoEU countries will take in over 60,000 refugees over next two years, Commission says