For several months, Ireland has seen an increase in migrants entering from the United Kingdom. The country, faced with a serious housing crisis, is struggling to welcome these new asylum seekers. Homelessness has become a common experience for those awaiting protection. InfoMigrants went to meet them.

Leslie Carretero, special correspondent in Dublin

Karim* is standing, staring into space, on one of the steps of a building in the south of Dublin, the Irish capital. Behind him, a sign reads: "To Let." The building, which once housed offices, is now empty, and the developers are looking for a company to take possession of the premises.

Below these unoccupied offices lies a different reality. The sidewalk is filled with people, and dozens of tents have been covering the asphalt for the past three weeks. Some tents are planted on the other side of the road, along the canal. A large blue tarpaulin covers the makeshift camp to protect it from bad weather. The camp is home to about 50 people of various nationalities.

On this sunny July afternoon, the atmosphere is peaceful in the neighborhood, away from the busy city center. "Many are sleeping or staying in shelters, others are in the city to recharge their phones, find food or take a shower," Karim, a 34-year-old Afghan, explained. He is the father of 10 children back home. He has been living on Dublin’s sidewalk for a week. When he arrived in Ireland on June 27, he was not given a spot in a center for asylum seekers.

For all those who have just arrived, especially single men, homelessness is a common experience in Ireland. Irish reception centers are often full and rarely accept new people. At the beginning of May, around 200 people camped for months in front of the International Protection Office (IPO). The camp was dismantled by the authorities. A few weeks later, another camp along the Grand Canal suffered the same fate. Since then, authorities placed barriers along the canal to make it impossible for people to settle.

This new camp, at the foot of an abandoned building, is now the largest in Dublin. But in the south of the city, it is not uncommon to come across an isolated tent in the garden of a church, near a canal or under a bridge.

Also read: Migrant tent camp returns to Dublin just days after clearance

'Even if you put on several blankets, you shiver from the cold'

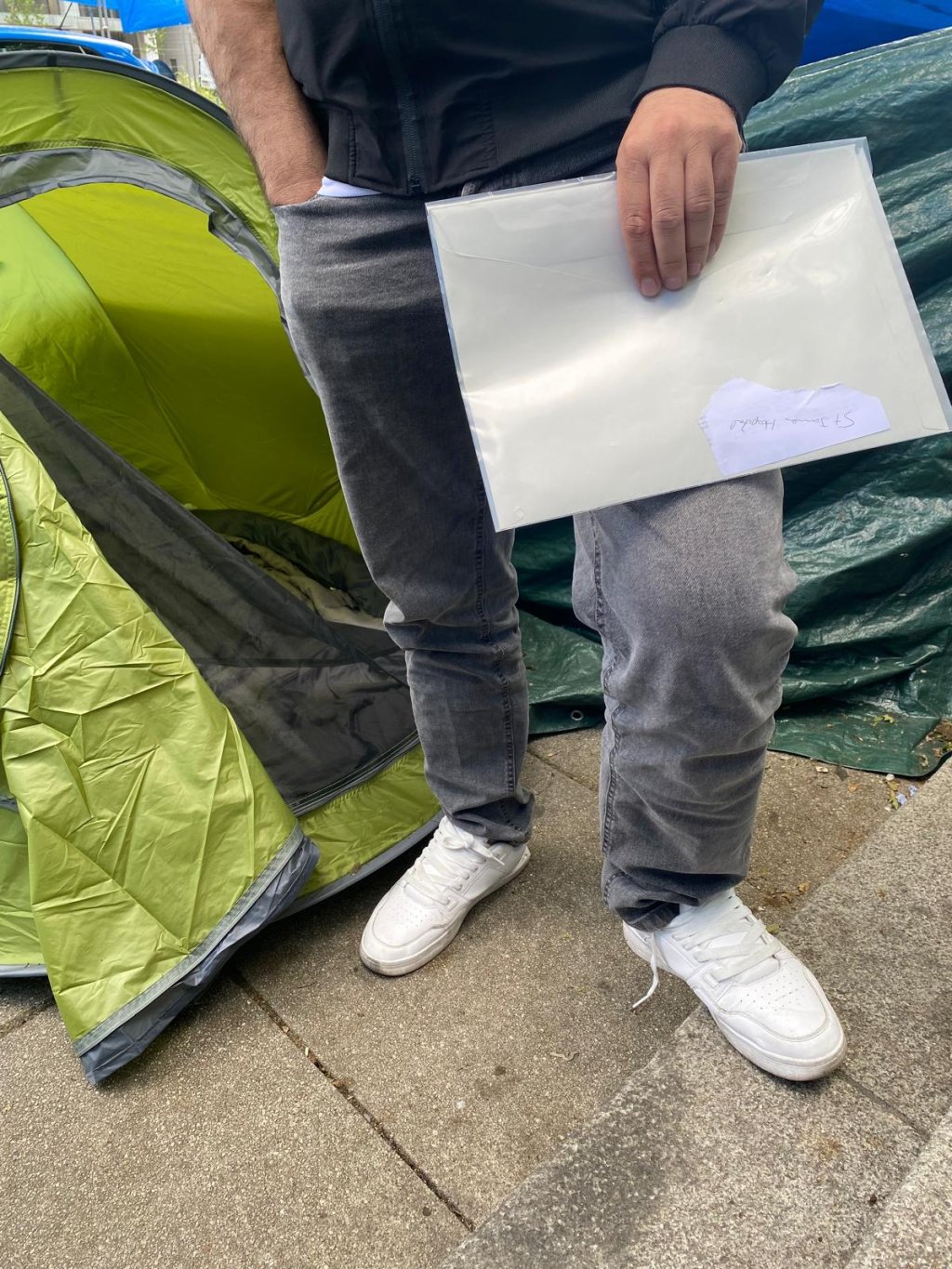

Karim takes a folder out of his tent. "This is what they gave me at the International Protection Office when I went to submit my asylum application," he says, handing the folder. He shows us the documents issued by the Irish asylum office: an asylum seeker certificate, a list of associations that help homeless people by providing food or tents, a letter stipulating that he benefits from financial assistance of 154 euros per week, notably for food — people housed by the state receive only 38 euros per week. For the rest, he has to manage by himself.

Ahmed, a Jordanian who has been living on the street for six months, tells the same story. "It’s very cold here, sometimes it prevents me from sleeping. Even if you put on several blankets, you shiver from the cold," the 34-year-old man told InfoMigrants. Behind him, the icy wind sweeps away the tarpaulins suspended above the tents.

Grainne Jones, an Irish activist, regularly visits the camp to help them. "This winter, they were under the snow, under the storm, in terrible conditions. At the moment, with the improvement in weather conditions, it is a little better but they are totally neglected by the state and have no access to basic services like toilets or showers," she said.

"To go relieve ourselves, we have to walk about six kilometers. We go to a mosque in the city that welcomes us," Sami*, another Afghan refugee, added. "Life here is so unbearable, I can’t take it anymore. I feel sad all the time."

Also read: Ireland to return asylum seekers to the UK by end of May

Nearly 10,000 accommodation requests since January

The Irish authorities themselves admit it: they are no longer able to meet the needs of newly arrived migrants, most of whom come from the neighboring United Kingdom. "Since January, 9,700 people arriving in Ireland have requested accommodation, an average of 389 per week. This is more than five times the 2017-2019 average," the Ministry of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth told InfoMigrants. Most asylum seekers in Ireland are from Nigeria, followed by Georgia and Algeria.

This unprecedented influx is linked to the United Kingdom's migration policy. The Conservatives — who lost the last legislative elections against Labor — planned to implement their infamous "Rwanda Plan" -- deportations to Kigali of people who entered British soil irregularly. Fear of these forced deportations has caused some asylum seekers to flee to Ireland, deemed more welcoming.

To try to meet growing demand, the Irish authorities hastily set up centers made of large military tents and bunk beds, but they are not enough to take care of everyone.

Also read: The rise of anti-migrant sentiment in Ireland

'The authorities do not want Ireland to appear as a welcoming country'

At the beginning of July, more than 2,200 people were still waiting to be assigned to a reception center, according to official figures. Some have to wait days, others weeks or even months.

In a letter sent back in May 2023 to the Irish government, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights expressed worry about the situation. Dunja Mijatović then called on the Irish authorities to reconsider "some of the more structural shortcomings of the international protection system," and requested they "work towards a more sustainable system of reception that firmly places the accommodation of refugees and asylum seekers within the context of the broader housing policy development and implementation."

A year later, the problem seems far from resolved. The housing crisis which has affected Ireland for several years is no stranger to this. Even the Irish can no longer find housing. The real estate market is tight in this country with no more than five million inhabitants. Some young people are forced to return to live with their parents at the end of their studies.

For activist Grainne Jones, the housing crisis argument is not the only one: "I also think that the authorities do not want Ireland to appear as a welcoming country. The government prefers that these people warn their friends about what they experience so that they don't try to come here."

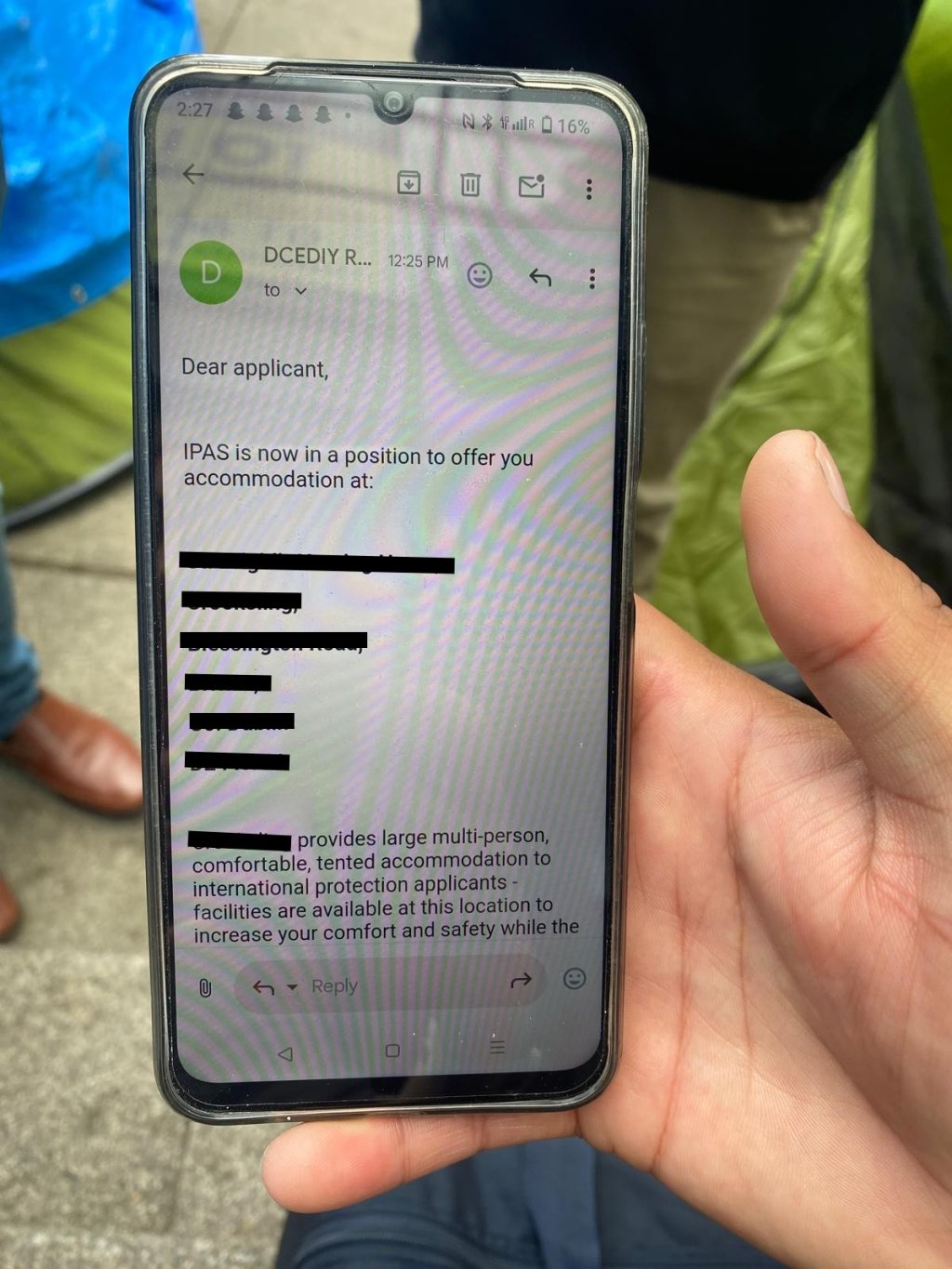

At the camp along the Grand Canal, Karim is now with three other Afghans. The young men gather their belongings. They have just received an email from the Ministry of Children, Equality, Disability, Integration and Youth stating: "We are now able to offer you accommodation," followed by the address of the place.

The four friends discover on Google Maps that their new home is 45 minutes away by car. They grab their backpacks and sleeping bags, then set off in search of a bus that can take them to their final destination, hoping for a new life.

*Names have been changed for anonymity

Also read: Ireland: Tensions over refugee crisis and Dublin tent cities