Two and a half months ago, a Syrian man was removed from his place in church asylum in Germany and deported to Denmark, where he is now reportedly in prison. The church authorities just made the case public, although it happened in February.

The story of a Syrian man who had been sheltering in church asylum in Germany and was deported to Denmark in February emerged at the end of April.

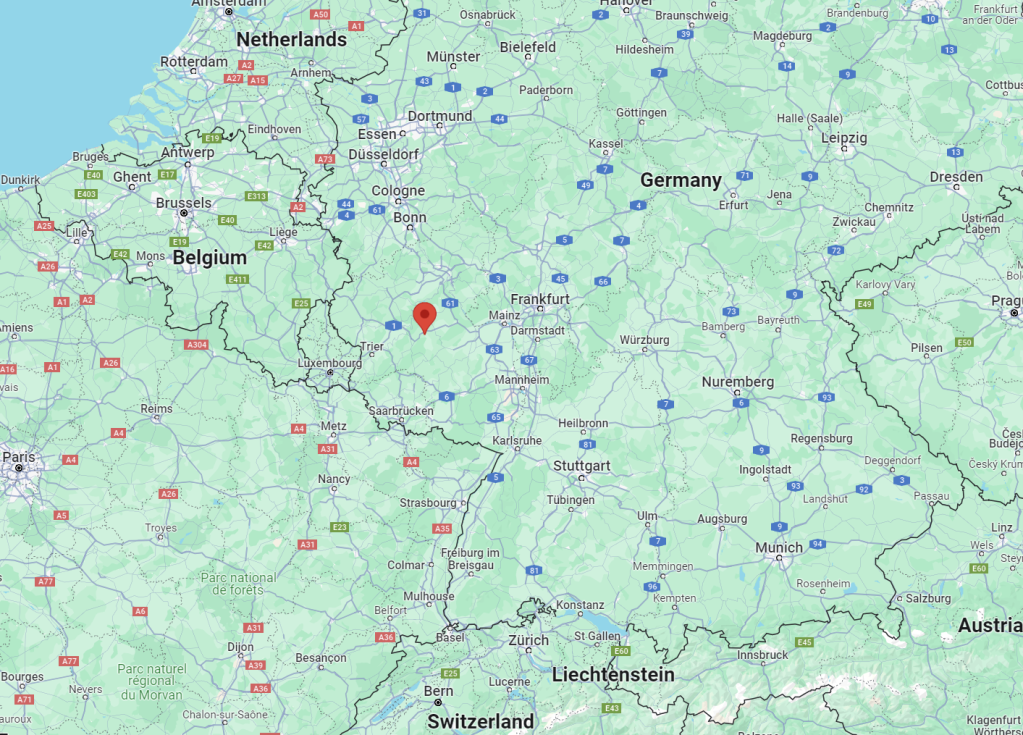

Dramatic scenes appear to have unfolded in an apartment in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate in February, reported the Protestant news agency epd on April 28.

In that apartment, police officers tried to arrest a Syrian Kurd sheltering under church asylum during a night-time operation. The man resisted and reportedly suffered lacerations. Despite a short hospital visit, police were then able to complete the deportation to Denmark, where he arrived some 12 hours after officers first entered his home.

Accounts of the night slightly differ. The superintendent of the Simmern-Trarbach church district told InfoMigrants the man fell down the stairs during a scuffle and then tried to injure himself by banging his head against the wall in desperation to avoid being deported. A spokesperson for the state administrative district in charge of the area says he exhibited "self-harming behavior" and tried to jump down the stairs.

The asylum seeker, named as Mohammed H., was living in an apartment rented by the Protestant church in the village of Büchenbeuren.

Going public

Although the deportation happened in February, the Protestant church decided to make the case public in April -- partly because it wanted to wait for the court to provide certain information like the search warrant, says the superintendent, Markus Risch.

The church district says it was "astonished" when it learnt that one of its rental properties for those sheltered under church asylum had been cleared during a night-time police operation without any prior contact being made, Risch explains.

"[Mohammed H.] is not a criminal under German law because he left the camp in Denmark illegally out of justified existential fear," Risch told InfoMigrants. "He was threatened with deportation to Syria, which would be unthinkable in Germany. What would we do in such a situation?" he wonders rhetorically.

After speaking to the church officials, it becomes clear that Mohammed H's case is complicated. Risch and Büchenbeuren's pastor Sandra Menzel, who in the past have faced charges for providing church asylum that were subsequently settled amicably, say they had a good rapport with the administrative district that was responsible for church asylum cases. Unbeknownst to them, however, H.'s case was handled by a different authority.

Although the churches have no special legal rights, church asylum is usually respected. It is considered the last resort when all other legal options have been exhausted, and it is usually only granted to people who are classified as hardship cases by the church itself.

Read more: Deportation raid at church property in northeast Germany results in chaos

Two failed asylum applications in Germany

Mohammed H.'s deportation wasn't the first time the Syrian was forcibly taken back to Denmark.

The Kurdish Syrian's odyssey started in 2014 when he fled his home country on the grounds he was facing torture and prosecution as well as forced military service. After initially being granted asylum and living in Denmark for some eight years, the now 31-year-old was facing deportation to Syria after the government declared Syria a 'safe country'.

In December 2022, he came to Germany, partly because his brother lived near Bonn. When his asylum bid was rejected at the beginning of 2023, he was deported to Denmark for the first time. Facing charges of leaving the departure camp without permission, he returned to Germany in June of last year and submitted a second asylum application, which was also in vain. As a last-ditch effort to stay in Germany, he requested church asylum in the church district of Simmern-Trarbach late last year.

In mid-November, the Protestant church district decided to accept the Syrian on its asylum program due to the exceptional circumstances of his case.

Sentence in Denmark

However, following his forcible return to Denmark in mid-February, a Danish court sentenced him to ten months in prison without probation. According to news agency epd, the public prosecutor's office has since appealed against the sentence arguing it is too lenient.

Denmark's migration policy has become increasingly strict. This has led to criticism by pro-migrant organizations for being hostile towards migrants and for increasingly restrictive policies on immigration and asylum. Last year, for instance, rights groups slammed the government's decision to declare more areas of Syria 'safe' to return to as a means of deporting migrants to the war-torn country.

Moreover, the government is pursuing the declared goal of reducing the number of asylum applications "to zero". In addition, the kingdom is trying to force people to go back to Syria on a so-called voluntary basis. Those who do not leave "voluntarily" can be housed in prison-like camps for an indefinite period of time as long as deportation is not possible, epd reported.

According to the German church, the Syrian Kurd had previously lived, worked and paid taxes in Denmark for years without attracting attention.

Approached by InfoMigrants, the Danish Immigration Services wrote "We cannot comment on any individual case unless the person involved authorizes a power of attorney stating their consent." Neuwied’s district administration told InfoMigrants the Danish authorities assured them Mohammed H. would not be deported to Syria.

Read more: Germany urged to follow Denmark's lead on migration policy

Dispute between the church and authorities

Back in Germany, the circumstances which led to Mohammed H.'s deportation have caused discord between the district administration and the church authorities. The district administration in Neuwied accuses the church district of not having followed the rules. "The person concerned was obliged to leave the country and did not comply with his obligation to leave, so that this had to be enforced", Neuwied states.

According to Superintendent Risch, the authority informed the Interior Ministry of Rhineland-Palatinate that Mohammed H. was a criminal offender. "We wish someone had talked to us before coercive measures were taken. We could have explained Mr. H.'s situation," Risch told InfoMigrants.

When approached by InfoMigrants about the accusations, Neuwied’s district administration says the reason for removing the Syrian out of church asylum is an alleged failure on behalf of the church district to comply with the usual procedure (laid out here) between the church and the state. Specifically, Neuwied claims the church district did not dismiss its guest after a so-called dossier was rejected by Germany's Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF).

According to the church asylum practitioners InfoMigrants spoke to, however, the vast majority of these dossiers are routinely rejected -- yet the church asylum is usually tolerated regardless.

Pastor Menzel calls the forcible removal from church asylum a failure on behalf of the responsible authorities to help him "obtain his rights".

"It was precisely because of such cases that the churches and the state government had agreed that church asylum should be possible under certain conditions and in cases of particular hardship," Menzel told InfoMigrants. "Such cases are even desired by the government in order to prevent precisely such unlawful acts."

In Rhineland-Palatinate, where the state government continues to publicly commit to a "humanitarian refugee policy", according to epd, there have been repeated police operations against church asylum in recent years.

The state Ministry of Integration told epd it had been informed in advance of the district's actions: "After the responsible immigration authority had already obtained a court search warrant for the residential building used by the church, there was no longer any reason to assess the authority's actions... differently."

Also read: Bremen court ruling: Benefits can be cut for migrants receiving church asylum

40 years of church asylum in Germany

As the number of asylum seekers in desperate situations asking to be accepted into church asylum is reportedly growing, many people seeking help now have to be turned down, Superintendent Risch says.

According to the network Asylum in the Church, the number of active cases has increased from some 430 in August last year to currently almost 600 involving at least 780 people, about 131 of whom are children.

Like with most church asylum cases, the goal of sheltering the Syrian was to gain time for the authorities to re-examine his asylum case.

Authorities usually only have six months to send people back. If the asylum seekers 'serve' this time in church asylum, the danger of deportation is averted. Afterwards, asylum seekers usually get a chance to apply or re-apply for asylum and might receive subsidiary protection thereafter.

These so-called Dublin cases -- named after where this EU regulation was signed -- make up the vast majority of people in church asylum in Germany. Most of them were first registered in another EU member state, often a country on the bloc's external border like Bulgaria or Croatia where human rights violations like pushbacks and detention are reportedly widespread, although state authorities there deny these take place.

The modern church asylum movement in Germany, which was sparked in 1983 by the suicide of Turkish asylum seeker Cemal Kemal Altun, has sheltered more than 10,000 asylum seekers over the past 40 years.

It is considered the last resort when all other legal options have been exhausted or when a deportation is imminent, and it is usually only granted to people who are classified as hardship cases by the church itself.